Eucatastrophe: Tolkien’s Catholic View of Reality

by Fr. Kent Grealy, F.S.S.P.

“Eucatastrophe” is a word coined by J.R.R. Tolkien in his important essay On Fairy Stories. This essay gives, as it were, the key to his view of the purpose and function of Fantasy – of Myth, in the true and good sense. “The eucatastrophic tale,” he writes, “is the true form of fairy-story, and its highest function.”1 Yet, since Myth in founded upon and draws from Reality,2 eucatastrophe is also a principle of the Primary World, of the Great Story God has chosen to tell in Creation.

What is eucatastrophe? Let us allow Tolkien to speak for himself – and we, especially as Catholics, will right away grasp the truth of his words, the profundity of his insight, and see the depths of his penetrating vision of Reality. Eucatastrophe is

the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous ‘turn’ (for there is no true end to any fairy-tale): this joy, which is one of the things which fairy-stories can produce supremely well… is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief…

[I]t can give to a child or man that hears it, when the ‘turn’ comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears…

The peculiar quality of the ‘joy’ in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth… in the ‘eucatastrophe’ we see in a brief vision that the answer [to the question ‘does the story have the inner consistency of reality?’] may be greater – it may be a far off gleam or echo of evangelium in the real world…3

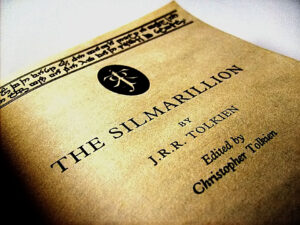

Eucatastrophe, then, is a word to describe that most important truth, that God brings good out of evil; that “where sin abounded, grace did more abound.”4 St. Augustine writes, “[God] would not allow any evil to exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil.”5 Evil, then, is permitted for the sake of some greater good. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Incarnation and Redemption – Christ, the God-Man, and He upon the Cross and then Risen triumphantly. “O happy fault that merited for us so great, so glorious a Redeemer,” as the Exultet proclaims. Evil serves Good, ultimately. As Tolkien has Eru Illúvatar say to Melkor (God and the Devil in his Legendarium, respectively): “no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in Me, nor can any alter the music in My despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but Mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined.”6 Nothing is outside of God’s Omnipotence; nothing is outside His Providence. In the end, everyone and everything serve His Glory. Writing of how eucatastrophe is found in Reality itself – for Reality, the Great Story, is indeed Catholic – Tolkien continues,

[I]t has long been my feeling (a joyous feeling) that God redeemed the corrupt making-creatures, men, in a way fitting to this aspect, as to others, of their strange nature. The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories… among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable Eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the Eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the Eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy. It has pre-eminently the ‘inner consistency of reality.’ There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many skeptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Art, that is, of Creation. To reject it leads either to sadness or to wrath.

How beautiful a vision of things this is! And it is simply what we all believe: Christ is the heart of the Great Story. He is the key to it all. Fallen humanity fought the “long defeat,”7 incapable of saving itself. Thus was necessary the Eucatastrophe of the Incarnation of the Son; only God could save us – and the Story He tells is unlike anything we could have dreamed. The power and truth of it pierce us to our very core like a sword, with utmost sorrow and highest joy woven together – become one.

All stories, aiming to have that ‘inner consistency of reality,’ need to be based on Creation, on the Evangelium, the Great Story. The better they are founded on Primary Reality, the more of the truth they will contain and show forth. This is why modernity is all but incapable of writing proper Fantasy – it has rejected the Gospel, and so has been blinded to Reality; its stories do not reflect the Light of the Evangelium, but rather the darkness, bitterness, misery, and despair of Fallen, sinful humanity bereft of God. Its fantasy is Anti-Fantasy, a corruption and mockery of true fairy-story. Modernity does not see or know the Great Story; indeed, it does not want to. And in its rejection of it is its ruin.

Tolkien goes on to write of how the Gospel, the climax and centre of the Great Story, has not done away with story – with Myth – but has raised and hallowed it:

It is not difficult to imagine the peculiar excitement and joy that one would feel, if any specially beautiful fairy-story were found to be “primarily” true, its narrative to be history, without thereby necessarily losing the mythical or allegorical significance that it had possessed. It is not difficult, for one is not called upon to try and conceive anything of a quality unknown. The joy would have exactly the same quality, if not the same degree, as the joy which the “turn” in a fairy-story gives: such joy has the very taste of primary truth. (Otherwise its name would not be joy.) It looks forward (or backward: the direction in this regard is unimportant) to the Great Eucatastrophe. The Christian joy, the Gloria, is of the same kind; but it is preeminently (infinitely, if our capacity were not finite) high and joyous. But this story is supreme; and it is true. Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men – and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused. But in God’s kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on. The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them, especially the ‘happy ending.’ The Christian has still to work, with mind as well as body, to suffer, hope, and die; but he may now perceive that all his bents and faculties have a purpose, which can be redeemed. So great is the bounty with which he has been treated that he may now, perhaps, fairly dare to guess that in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation. All tales may come true; and yet, at the last, redeemed, they may be as like and as unlike the forms that we give them as Man, finally redeemed, will be like and unlike the Fallen that we know.8

Grace does not destroy nature, it perfects it – transfigures it.

Tolkien’s word Eucastrophe captures the ‘inner consistency of reality,’ as it describes how God Himself tells the Great Story. “’Thus even as Eru spoke to us shall beauty not before conceived be brought into Eä [Reality], and evil yet be good to have been.’… ‘And yet remain evil.’”9 While not denying evil’s reality and power, we deny its final victory. “[E]vil labours with vast power and perpetual success – in vain: preparing always only the soil for unexpected good to sprout in.”10 That is our Christian Joy: to the glory of God, the Great Story, with Christ at its centre, has a happy ending.

Fr. Kent Grealy, F.S.S.P., was born and raised in Victoria, BC, Canada – his Shire. He considers Tolkien to be his first teacher in the Faith, who showed him that Reality is Catholic. Fr. Grealy styles himself a ‘Tolkienian Thomist.’ He is currently assigned to Holy Family Parish in Vancouver, BC, Canada, and rejoices to be living on the West Coast once again.

-

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf, ‘On Fairy Stories,’ (HarperCollins Publishers: London, 2001), p. 68.

- Cf. Ibid., pp. 55, 59, 71.

- Ibid., pp. 69, 71.

- Rom. 5:20 [Douay-Rheims].

- St. Augustine, Enchiridion, Ch. 11.

- J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, ‘The Ainulindalë,’ (HarperCollins Publishers: London, 1999), p. 5f.

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter n. 195, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter, (HarperCollins Publishers: London, 2006), p. 255.

- Tree and Leaf, pp. 71-73.

- The Silmarillion, ‘Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor,’ p. 108f.

- Letter n. 64, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, p. 76.

March 25, 2023