When Casper May Not Be So Friendly

There was an interesting article last week in Crisis Magazine by Kennedy Hall titled Has Jordan Peterson (Finally) Found Christ?

For Peterson devotees, it would be a much hoped-for discovery after quite a long and windy journey. The article however, which comments on a recent interview, seems to suggest he is coming close but is not there yet.

Like those final and unrestful moments of sleep when the body knows it needs to get up and face the day, Peterson’s journey from secularist to believer carries its share of fascination, for taking that step out of the boat to walk on the stormy waters is certainly terrifying, as he describes.

Perhaps Newman’s words come to mind: Once you have seen a ghost, you can’t go on pretending like you have not seen it.

Peterson certainly has his critics, and a lot of them, but the question is why. Knowledge based off sound bites and woke clichés is no match for an intelligent man sincerely searching for meaning with the courage to ask hard questions. This stirs up controversy because Peterson can state and maintain his point of view from the stance where he is currently at, all the while carrying a willingness to change that if he can be given a compelling reason to do so. This is quite different from many of his secular counterparts. Hall states as much:

Peterson was asking real questions that he wanted real answers to, rather than simply calling into question the ideas of our age while laying his own doctrines on top.

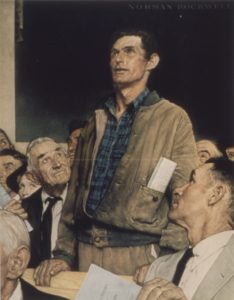

That is the real point of dialogue and exchange of ideas, which is the essence of free speech, and is the specific difference between education and indoctrination. The problem with our woke cancel culture is that it cannot tolerate any challenge, lest the superficiality of its doctrines is exposed; it is easier to shout someone down than to critically think through something and face the consequences. Genuine discussion and rational argument take effort and time, and can be uncomfortable, especially when positions that are deeply-held are taken to task. Peterson is willing and able to do the hard work of thinking, and challenges others to do the same.

That is the real point of dialogue and exchange of ideas, which is the essence of free speech, and is the specific difference between education and indoctrination. The problem with our woke cancel culture is that it cannot tolerate any challenge, lest the superficiality of its doctrines is exposed; it is easier to shout someone down than to critically think through something and face the consequences. Genuine discussion and rational argument take effort and time, and can be uncomfortable, especially when positions that are deeply-held are taken to task. Peterson is willing and able to do the hard work of thinking, and challenges others to do the same.

Perhaps that is why he is a fascination to some, a menace to others.

Peterson recognizes that man is a creature in history, and that history carries its own authority and accumulated wisdom which, when ignored, has serious consequences. He seems to derive his respect for the Sacred Scriptures from this standpoint, along with their being foundational for Western Civilization. He claims the Scriptures we have today are the product of an editing process perfected through history. Amidst Peterson’s quite salient psychological commentaries on various episodes and characters in both the old and new Testaments (one hopes he may discover Fulton Sheen!), Christ emerges as a mythical and archetypal figure, representing the absolute best of humanity.

The challenge to this is that the figure of Christ, as portrayed in four separate Gospel narratives with four distinct writers, is so without flaw that it is impossible for this to be of purely human literary construct.

No matter how long and sensitive the editing process, flawed men, even collectively, cannot construct such a perfect and consistent Character where all virtues are so completely harmonized and blended. As we cannot give what we do not have, any literary figure is going to necessarily possess flaws. Try, try as we may, in bringing forward one virtue, we must militate upon another: like humility against fortitude. This makes the case for the reality of divine inspiration because only God knows what perfection is, and so can guide inspired writers to portray it with all due precision.

Of course, this requires faith, which is so scorned by the intelligentsia. They say that it is not demonstrable, is a matter of opinion, antiquated, an insult to intelligence, or just an excuse for ignorance of those who don’t want to think; hence a bumper sticker that reads If you don’t pray in my schools, I won’t think in your churches. But that is not faith, which, if correct, must be in accord with sound reason, including submission to an authority higher than human reason.

And Peterson has thought through things and, almost alarmingly, finds himself apparently at the limit of where his thought, learning, and experience can take him; now at a place where he has to confront the real possibility that the archetypal Jesus is actually a real Person, that there is a Christ of history that is identical to his “Christ of myth,” who is actually identical to the Christ of faith.

In other words, the Gospel accounts are both historical and accurate in every way.

For a man like Peterson, or anyone sincerely searching, at some point the only real access to Jesus Christ is through an act of faith, aided by grace, in His claim to be God. After that, Christ will bring plenty of sense to sufferings and trials, and real meaning and purpose to life. That comes at a cost, because the Cross cannot be just a story, a myth, no more than the Resurrection can be.

That’s the whole point of salvation history, for our Lord throws down the gauntlet with the challenge Who do you say that I am? To watch Peterson work himself to this point and struggle with the reality of the correct answer, and how it will profoundly impact the rest of his life, should give us pause to consider the impact it should have on ourselves as believing Catholics.

But if we lack the courage to do so, it may be best to distract oneself through the whole of Passiontide, and go on pretending there are no such things as ghosts.

March 17, 2021