Afonso I: the Constantine of the Congo

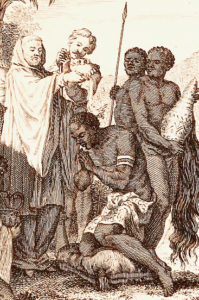

On June 4th, in the year of Our Lord 1491, a Congolese Prince named Nzinga Mbemba was baptized by Portuguese missionaries, taking the name of Afonso.

On June 4th, in the year of Our Lord 1491, a Congolese Prince named Nzinga Mbemba was baptized by Portuguese missionaries, taking the name of Afonso.

By 1509, his father the King of Kongo had died, touching off a war for succession that fractured the kingdom along a religious fault line. On the one side was the Catholic Afonso, and on the other his pagan half-brother Mpanzu a Kitima.

The two rivals met in a decisive battle at the capital of Mbanza Kongo, and what happened next is the stuff of Catholic legend. According to Afonso’s own account, his vastly outnumbered army appealed to St. James for assistance. The great Apostle then miraculously appeared in the sky along with five heavenly swordsmen, and the sight so frightened the pagans that their superior force broke and abandoned the field.

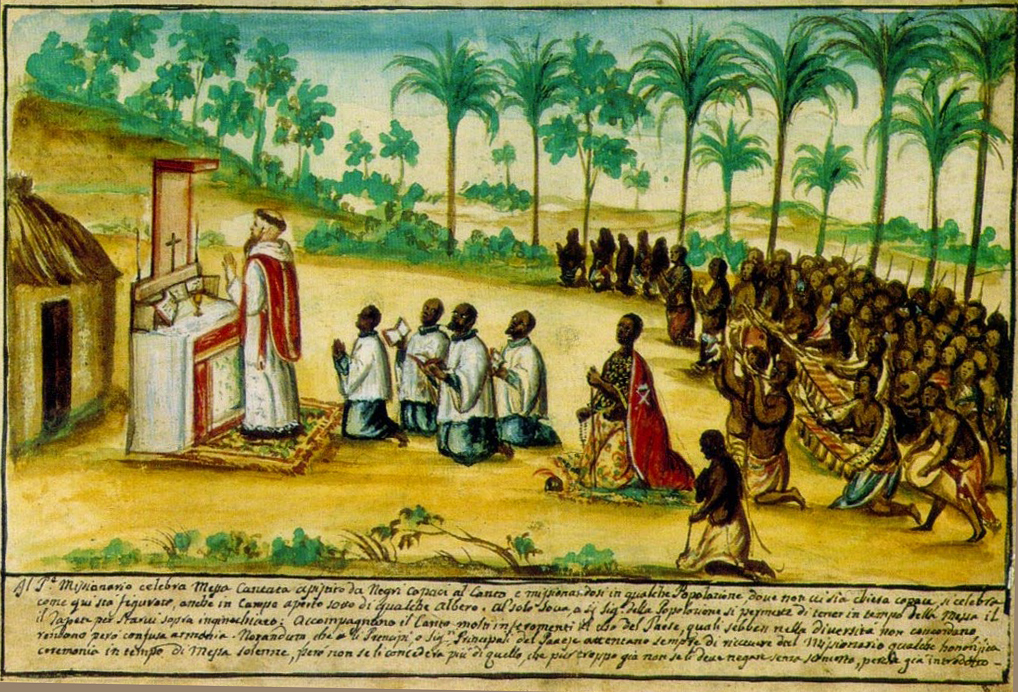

Afonso thus succeeded his father as Manicongo. Bolstered in his convictions by a wondrous act of divine aid, this Constantine of West-Central Africa did everything he could to shift the kingdom away from its traditional paganism and toward the Catholic religion. To commemorate his victory, he devised a coat of arms emblazoned with five sword-arms, the scallops of St. James, and broken idols. He made the feast of St. James a national holiday. He established Catholicism as the state religion of the Kongo, declared the worship of idols illegal, and burned a pagan temple. He encouraged the founding of confraternities, as well as missionary schools that instructed the Congolese aristocracy in Christian doctrine and in Latin. His son was even ordained a bishop by Pope Leo X. Afonso did so much to advance the Catholic faith during his reign that a contemporary Portuguese historian dubbed him “the Apostle of Congo.”

Afonso thus succeeded his father as Manicongo. Bolstered in his convictions by a wondrous act of divine aid, this Constantine of West-Central Africa did everything he could to shift the kingdom away from its traditional paganism and toward the Catholic religion. To commemorate his victory, he devised a coat of arms emblazoned with five sword-arms, the scallops of St. James, and broken idols. He made the feast of St. James a national holiday. He established Catholicism as the state religion of the Kongo, declared the worship of idols illegal, and burned a pagan temple. He encouraged the founding of confraternities, as well as missionary schools that instructed the Congolese aristocracy in Christian doctrine and in Latin. His son was even ordained a bishop by Pope Leo X. Afonso did so much to advance the Catholic faith during his reign that a contemporary Portuguese historian dubbed him “the Apostle of Congo.”

Historians have long debated the extent to which the Kingdom of Kongo was actually Christianized during this period–and even whether Afonso’s own faith was as sincere as he portrays. But this is nothing new. Historians ask the same questions of Constantine and, really, any leader who throws his political weight behind the Church.

But one testament to the sincerity of Afonso’s faith was his apparent willingness to cling to its tenets even as relations deteriorated with those who had first brought it. For as it happened, some of those very people who ostensibly came to preach Christ crucified were enticed to follow Mammon instead.

Slavery had existed from time immemorial in the Congo, mainly consisting of criminals and prisoners of war condemned to serve in aristocratic households. But the growth of an international market for slaves, and the massive profits it generated, pushed many Portuguese and Congolese away from a low-key domestic model toward what one historian has called “a mercantile economy based on chattel slavery and ruthless greed.”

Afonso grew increasingly alarmed about the insidious and illegal trafficking of his subjects, and in 1526, he wrote an impassioned letter to John III of Portugal–one Catholic king to another.

“Each day the traders are kidnapping our people – children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family. This corruption and depravity are so widespread that our land is entirely depopulated. We need in this kingdom only priests and schoolteachers, and no merchandise, unless it is wine and flour for Mass.“

He told the Portuguese King that the slavers were “ruining our kingdom and the Christianity which has been established here for so many years and which cost your predecessors so many sacrifices.” He appealed to the king’s missionary impulse to provide “this great blessing of faith” to new peoples–and said he was anxious to preserve that faith intact in the Congo. But:

“…European goods exert such a fascination over the simple and the ignorant that they leave God in order to obtain them…The lure of profit and greed lead the people of the land to rob their compatriots, including members of their own family and of ours, without considering whether they are Christians or not. They capture them, sell them, barter them. This abuse is so great that we cannot correct it without striking hard and harder.”

From our 21st century vantage point, it is easy to posture and preen in imperious judgment of men long since dead, and to force complex historical circumstances into boilerplate soundbites and stale 19th century political theories. We conveniently imagine ourselves on the right side and hardly dare ask what fascinating merchandise and bits of modern technology we’ve traded God for.

Afonso, however, who saw the birth of the Atlantic Slave Trade before his very eyes, was not interested in cheap virtue signaling.

Whether he was defending his succession against pagan relatives or defending his kingdom against a Christian foreigner, whether he was inveighing against the hypocritical greed of Christian traders or the heartbreaking selfishness of his own people, one thing seems fairly consistent in his rhetoric: a fidelity to God’s law.

King Afonso I of Kongo died in 1542, unable to snuff out the slave trade in its infancy. In ensuing years, it would metastasize into an intercontinental nightmare that would see some 10-12 million Africans brought across the Atlantic in chains, over a million of them perishing along the way. It is not hard to imagine what the writer of those letters would have felt about the future, had he lived to see it.

Because of the precedents Afonso established, the Kingdom of Kongo was set on a religious course that it maintained for centuries afterward. His successors were duly recognized as Catholic Monarchs by the Pope and the Royal Houses of Europe, who extended to the African nobility such European titles as Count and Duke. The kingdom would, however, continue to be beset by internal dissension and external conflict until it was weakened and finally abolished in 1914, during a decade that proved fatal to so many of the ancient monarchies of Christendom.

Because of the precedents Afonso established, the Kingdom of Kongo was set on a religious course that it maintained for centuries afterward. His successors were duly recognized as Catholic Monarchs by the Pope and the Royal Houses of Europe, who extended to the African nobility such European titles as Count and Duke. The kingdom would, however, continue to be beset by internal dissension and external conflict until it was weakened and finally abolished in 1914, during a decade that proved fatal to so many of the ancient monarchies of Christendom.

Afonso, like Constantine, is not ultimately to be judged by the miraculous events that surrounded his accession, the geopolitical situation he navigated, or even the longevity of his nation. He is to be judged–as all of us are–by one thing alone: how did he respond to the graces that God gave him?

It is not for history to answer that question. But there is good reason for the Catholics of today, particularly those descended from his subjects, to admire this loyal son of Holy Mother Church who forged an island of Christendom in the heart of the Congo.

July 10, 2020