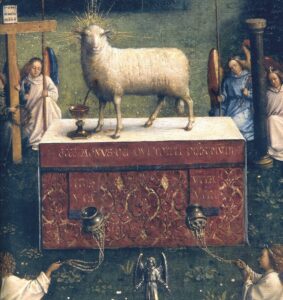

Christ the Lamb

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

During the Easter Season, Our Lord as the Lamb (Agnus in Latin) takes a predominate place in the Church’s liturgy. In the Preface of Paschaltide, the Church sings: “Christ our Pasch [Passover Lamb] was sacrificed. For He is the true Lamb Who hath taken away the sins of the world (Pascha nostrum immolátus est Christus. Ipse enim verus est Agnus, qui ábstulit peccáta mundi).” During the Easter Octave, in the Sequence, the following is chanted: “Christians! to the Paschal Victim offer your thankful praises. The Lamb the sheep redeemeth (Víctimæ pascháli laudes ímmolent Christiáni. Agnus rédemit oves).” At Vespers of the Season, the Church hymns about the “Lamb’s high feast (Ad régias Agni dapes)” and Christ the Paschal Lamb (“Iam Pascha nóstrum Christus est“) who was sacrificed. The phrase “Christ our Pasch [Passover Lamb] is immolated (Pascha nostrum immolátus est Christus)” is found both in the Epistle and Communion of the Easter Sunday Mass (1 Cor 5:7).

Of course, it is not only during the Easter Season that Our Lord is presented as the Lamb. In the Gloria, He is invoked as the “Lamb of God” (Agnus Dei). After the commixtio of the particle broken from the Host and the consecrated Wine, the Church asks for mercy and peace from the “Lamb of God” (Agnus Dei). When Holy Communion is distributed, He is presented to the faithful as the “Lamb of God” (Ecce Agnus Dei). However, during the Easter Season, Our Lord as the Lamb is given, as was said above, a predominate place.

Referring to Christ as Lamb has its foundation in Sacred Scripture. At the banks of the Jordan River, St. John the Baptist pointed out Our Lord with the words: “Behold the Lamb of God. Behold him who taketh away the sin of the world” (Joh 1:29). This harkens back to the first book of the Old Testament. When Abraham and his son Isaac were making their way to the place of sacrifice appointed by God, Isaac asked his father (Gen 22:7), “Behold, saith he, fire and wood: where is the victim for the holocaust?” His father prophesied, “God will provide himself a victim for an holocaust” (Gen 22:8). The word translated here as “victim” is, in the Greek Septuagint, πρόβατον,1 which more specifically means “sheep.” The Hebrew is השׂה, “ewe, lamb, sheep.”2 An angel stops Abraham before he sacrifices his son and, in his place, they offer a ram (Gen 22:13). Centuries will pass until Abraham’s prophesied Lamb will be provided and sacrificed.

Our Lord symbolized as Lamb is found as well in the last book of Holy Scripture, where St. John the Apostle wrote that he saw in his vision “a Lamb standing, as it were slain, having seven horns and seven eyes: which are the seven Spirits of God, sent forth into all the earth…the Lamb which was slain from the beginning of the world…worthy to receive power and divinity and wisdom and strength and honour and glory and benediction” (Apo 5:6, 13:8, 5:12). He also tells of the “the wrath of the Lamb” (Apo 6:16) which will fall upon sinners.

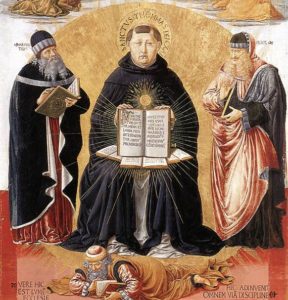

But the question naturally arises, why is the lamb a fitting symbol of Our Lord? Now a lamb is a young sheep. As St. Thomas Aquinas, quoting an earlier work, wrote, a sheep is useful in four ways: “for sacrifice, for meat, for milk, and for its wool” (S.T. I-II, q. 105, a. 2, ad 9). How each of these can be applied to Christ will be treated in turn.

For Sacrifice. The lamb was a common sacrificial victim under the Old Law (e.g., Exo 29:39-41). Particularly, the sacrifice of lambs was the principal daily sacrifice. Every day, a lamb was to be offered in the morning and in the evening. The sacrifice of a lamb was also an essential feature of the Passover ceremony (see Exo 12:1-28). In His self-sacrifice upon the Cross (Heb 9:14, Isa 53:7), Christ is compared to a lamb – “He was led as a sheep to the slaughter: and like a lamb without voice before his shearer, so openeth he not his mouth” (Act 8:32, see Isa 53:7); “knowing that you were not redeemed with corruptible things…but with the precious blood of Christ, as of a lamb unspotted and undefiled” (1 Pet 1:8-19). As the sacrifice on the Cross is the principal and essential sacrifice of all sacrifices, it is fitting, in this respect, that Christ is represented as a lamb.3

For Meat. In general, sheep, and thus lamb, can be used for food. In the Old Law, the eating of lamb took on a religious significance in the consumption of the Passover Lamb. Our Lord, in the midst of a Passover celebration, gave His Body, under the appearance of Bread, to His Disciples to be eaten. Until His Second Coming, Our Lord continues to feed His faithful with His Body in Holy Communion.

For Wool. The coats of sheep and lambs can be shorn and used for wool. This wool is then used to make clothing and other textile products. By clothing oneself with wool, one is, after a fashion, clothing oneself with the lamb from which the wool came. When one is sanctified by the grace merited by Christ on the Cross, it can be said that one is symbolically being clothed by grace and thus by the one Who merited it. This concept is expressed by the Holy Ghost through the Apostle Paul in his writings – “put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ: and make not provision for the flesh in its concupiscences” (Rom 13:14), “for as many of you as have been baptized in Christ have put on Christ” (Gal 3:27). But, it is important to note, that this language is symbolic. When one is sanctified, there is an intrinsic, that is an internal, real yet supernatural change in one’s soul. Putting on clothing is an extrinsic, or external, change.

For Milk. While only mature female sheep produce milk, this, after a fashion, can still be attributed to Our Lord. According to St. Peter, milk (rationale/rationabiles lac) can be seen as symbolic of heavenly doctrine (1 Pet 2:2, the Introit for Low Sunday).4 Heavenly doctrine, of course, was preached par excellence by Our Lord. It could also be said that just as milk, a nourishing drink, flows from the sheep, so did a spiritual drink flow from Our Lord’s Heart opened on the Cross, which drink, His very Blood, is received under the appearance of Wine.

But the above does not exhaust the symbolic value of a lamb representing Christ. In his commentary on the Gospel of John (n. 258), St. Thomas, in explaining why Our Lord is called the Lamb of God by John, wrote the following:

Christ is called a lamb, first, because of his purity: your lamb will be without blemish (Exod 12:5); you were not redeemed by perishable gold or silver (1 Pet 1:18). Second, because of his gentleness: like a lamb before the shearer, he will not open his mouth (Isa 53:7). Third, because of his fruit; both with respect to what we put on: lambs will be your clothing (Prov 27:26), put on the Lord Jesus Christ (Rom 13:14); and with respect to food: my flesh for the life of the world (John 6:52). And it is said: send forth, O Lord, the lamb, the ruler of the earth (Isa 16:1).

In answer to the question posed above, there are many reasons why it is fitting that Our Lord is symbolized by a Lamb, both in Sacred Scripture and in the Church’s Liturgy, for this representation brings to mind sacrifice, meat, wool, milk, purity, gentleness (and, yet, also wrath at the proper time). By reflecting on these, the faithful can better understand this Lamb Who sacrificed Himself for them, His sheep, especially during the Paschal Season.

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

- Strong, G4263.

- Strong, H7716.

- See also St. Thomas’ Commentary on John, n. 257.

- See Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, 7 (Paschal Time Book I). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), p. 300.

April 19, 2024

The Psalms of Easter Matins

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

The Divine Office is a collection of Psalms, hymns, and prayers assigned for each day, which are then in turn distributed over different “hours” which historically correspond with different times of the day. Matins, for its part, is the hour associated with the middle of the night. Normally, the Divine Office is so arranged that one would ideally pray all 150 Psalms over the course of the week, but the Octaves of Easter and of Pentecost stand apart, as the same Psalms are prayed every day. Additionally, except during the Octave of Easter and the Octave of Pentecost, Matins never has less than nine Psalms (or a combination of Psalms and divisions of Psalms). During the Octaves of Easter and Pentecost, Matins only has three Psalms. The three Matins Psalms of the Easter Octave are the first three Psalms of the Book of Psalms. These first three Psalms serve as a summary of salvation history. They express the distinction between good and evil, the conflict between God and His Christ, on the one hand, and their Enemies, on the other, and Their victory through the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of the same Christ. As such, it is eminently fitting that they alone are prayed during the Easter Octave.

In the First Psalm, the way of life and the way of death and the distinction between good and evil is expressed by comparing the Just and the Unjust Man:

Blessed is the man who hath not walked in the counsel of the ungodly, nor stood in the way of sinners, nor sat in the chair of pestilence…he shall be like a tree which is planted near the running waters, which shall bring forth its fruit, in due season. And his leaf shall not fall off: and all whatsoever he shall do shall prosper. Not so the wicked, not so: but like the dust, which the wind driveth from the face of the earth…For the Lord knoweth the way of the just: and the way of the wicked shall perish.

The Second Psalm describes the conflict between God and His Christ, the Just Man par excellence, and Their enemies:

Why have the Gentiles raged, and the people devised vain things? The kings of the earth stood up, and the princes met together, against the Lord and against his Christ. [Now speaking in the voice of the Christ] But I am appointed king by him over Sion his holy mountain, preaching his commandment… [Now speaking in the voice of God] Ask of me, and I will give thee the Gentiles for thy inheritance, and the utmost parts of the earth for thy possession.

Additionally, this Psalm expresses the eternal generation of the Son by the Father (“The Lord hath said to me: Thou art my son, this day have I begotten thee”), the Son Who assumed to Himself a Human Nature and became the Christ, the Anointed One of God. It also looks forward to the Church spreading among the nations by the preaching of the Apostles, thus making the ends of the earth the possession and inheritance of Christ the King.

The Third Psalm details how the Christ is to come into His Kingship and defeat His enemies. Again, speaking in the Voice of Christ:

Why, O Lord, are they multiplied that afflict me? many are they who rise up against me. I have cried to the Lord with my voice: and he hath heard me from his holy hill. I have slept and taken my rest: and I have risen up, because the Lord hath protected me.

The Just Man, Who is also Christ the King, the Incarnate, eternally begotten Son, defeated His enemies and received His Kingship through His suffering, His death (“I have slept and taken my rest”), and His Resurrection through God’s power (“I have risen up”). Christ truly died and truly rose from the dead with the same Body and Blood which He had taken of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

These are reflections which the Church would have those praying Matins meditate on during this Easter Octave, and you, dear faithful, are invited to do the same.

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

March 31, 2024

‘I am a Christian…and in fact a Roman Catholic’

by Fr Brendan Boyce, FSSP

The 20th century, as every competent analysis concludes, was largely one of marked – and deleterious – upheaval at almost every level of human experience: social, political, technological, military and, yes, religious. And yet, amidst the horrors of the age, like a lamp shining in the darkness, this same century saw the flourishing of Catholic literary endeavour of, at times, a most poignant expression.

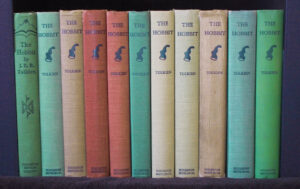

There are Catholic literary giants of the 20th century who need no introduction; individuals such as G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc and Evelyn Waugh, to name but a few. However, the person of J.R.R. Tolkien,1 while generally acknowledged to have been a great author, is not often associated in the same way as these others as a particularly Catholic author.2

In one sense, this is understandable. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, for example, does not proclaim itself to be Catholic, at a surface reading, in the same way as Brideshead Revisited; nor even as generically Christian, as does C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. But all this is to put the cart before the horse, because what should be first in our gaze on the works of Tolkien is the man himself.

And Tolkien was nothing if not a (very devout) Catholic. His own words bear this out (to give two examples among many); firstly in a letter written to his son Christopher in 1941, in the midst both of the Second World War and the writing of what was to become the Fellowship of the Ring:

Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament….There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth, and more than that: Death: by the divine paradox, that which ends life, and demands the surrender of all, and yet by the taste (or foretaste) of which alone can what you seek in your earthly relationships (love, faithfulness, joy) be maintained, or take on that complexion of reality, of eternal endurance, which every man’s heart desires.3

Just over 20 years later in 1963, writing again to the same son, Tolkien displays once more the great depth of his faith with regard to the Blessed Sacrament:

The only cure for sagging of fainting faith is Communion. Though always Itself, perfect and complete and inviolate, the Blessed Sacrament does not operate completely and once for all in any of us. Like the act of Faith it must be continuous and grow by exercise. Frequency is of the highest effect. Seven times a week is more nourishing than seven times at intervals. I witnessed (half-comprehending) the heroic sufferings and early death in extreme poverty of my mother who brought me into the Church; and received the astonishing charity of [Father] Francis Morgan. But I fell in love with the Blessed Sacrament from the beginning – and by the mercy of God never have fallen out again…4

Other examples abound of Tolkien’s firm adherence to the Faith throughout his life, from his devotion to Our Lady and attendance at daily Mass, to the testimonies of his family and life-long friends to his deep faith. Allowing this representation to stand, then, the question of the impact of his faith on the writing of his works may be considered.

Tolkien himself gives us the clearest insight into answering the question. In his view, it was impossible for an author to ‘disentangle’ faith and art. Tolken felt deeply that the writing of fantasy (and by extension all literary output) is a natural human activity and right. This conviction was based on his adherence to Catholic teaching (and biblical truth) that human persons are made in the image and likeness of God. Further to this is that since God creates, one would unquestioningly be less than human if one were not to express the ‘creative’, or ‘sub-creative’, side of one’s nature. In his important essay, On Fairy Stories, Tolkien declared: ‘…we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.’5

Holly Ordway, in her impressive and very readable work Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography, notes that art necessarily reflects something of the artist’s most deeply held beliefs, at least at some level, however subtle or implicit. For Tolkien, faith was not merely a set of superficial opinions, but something integral to his real character – and to his own self-understanding as an author of fiction.6 She continues: ‘So, it follows that if we are to understand and appreciate Tolkien’s writings to the fullest degree, we need to come to an understanding of what he himself identified as central to his identity: his faith, which could not be disentangled from his art.’7

In considering, then, the works of Tolkien, such as The Lord of the Rings, these things must be borne in mind. Further to that, we have Tolkien’s own view upon these matters, written to his friend Robert Murray SJ, who had commented upon elements of the work itself, with a particularly Catholic point of view:

The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.8

This is the sense, then, in which we must see The Lord of the Rings as a ‘fundamentally religious and Catholic work’, because it is in the intention of the author. Not for Tolkien the unabashed allegory of the Narnia Chronicles; nor the ‘realism’ of a Brideshead Revisited. His work is imbued in a manner redolent of that quiet, unhurried, gentle way of the working of grace in its harmony with matters of the Faith. One of his avid readers perhaps captures this best: ‘You…create a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp.’9

Greater writers than I, in works more mature than this, have delved into discussions of what is Catholic in The Lord of the Rings; but let us at least allude to some of these elements here. They range from the simple – such as the Fellowship departing from Rivendell on Christmas Day, or, if it is not giving too much away, the fall of Sauron on the Feast of the Annunciation/Incarnation – to the more profound, such as the roles of heroic self-denial and mercy and the presence and effect of lembas, the Elvish way-bread which is evocative of the Eucharist, particularly in its effects (feeding the will of those who rely upon it alone10). In the words of characters, also, we may discern sometimes more fundamentally religious and Catholic sentiments, such as in the inn at Bree, where Aragorn, despite his high destiny, states his willingness to give his life to protect Frodo; or at the Council of Elrond, in Frodo’s act of faith in being prepared to take the ring, though he does not know the way; or, most strikingly, Gandalf’s words to the Balrog upon the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, as one good angelic figure faces down a fallen angel, that he is (for those who have ears to hear) the servant of the Secret Fire (the One God) and that the dark fire of Udûn (hell) shall not avail the balrog. Beyond this work too, especially in The Silmarillion and other early (posthumously published) works, the influence of his faith may be even more readily discerned.

What matters in all of this is that we are not afraid to name a work Catholic, and to understand that it is Catholic, when its author is Catholic and when this author calls his work Catholic, even when that work may not be to our taste, or even when that work may be in a genre not necessarily ‘recognised’ as Catholic. For Catholicism has always found expression in various forms of art, from visual art to music to the written word, and within these modalities are various forms, which in their own unique way grant access, to those who are disposed, to the great truths of the Faith. We should see The Lord of the Rings, among Tolkien’s other works, as firmly (if uniquely) ensconced within the Catholic literary tradition of the 20th century, as a signal contribution to the light of our beautiful faith within the darkness of our modern age. Suggested further reading:

Suggested further reading:

- B.J. Birzer, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle Earth (Tempus, Stroud, UK, 2006).

- L. Coutras, Tolkien’s Theology of Beauty: Majesty, Splendor, and Transcendence in Middle-earth (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2016).

- A. Freeman, Tolkien Dogmatics: Theology through Mythology with the Maker of Middle-earth (Lexham, Bellingham WA, 2022).

- P. Kerry and S. Miesel, Light Beyond all Shadow: Religious Experience in Tolkien’s Work (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Madison WI, 2011).

- H. Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography (Word on Fire Academic, Grove Village IL, 2023).

- J. Pearce, Tolkien: Man and Myth (Harper Collins, London, 1998).

- J.R.R. Tolkien, The Nature of Middle-Earth (ed. C. Hostetter) (Harper Collins, London, 2021), especially Appendix I, ‘Metaphysical and Theological Themes’, pp. 401-412.

Fr Brendan Boyce FSSP was born and raised in New Zealand (also known as Middle-earth). He is currently posted to the FSSP apostolate in Canberra, Australia, but remains hopeful of one day being sent, like Gandalf, back to Middle-earth.

- The title of this article is taken from Tolkien’s Letter n. 213 (J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter n. 213, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter, [HarperCollins Publishers: London, 2006].)

- Another example of this would be the American author Flannery O’Connor (+1964), whose faith informed her writing to a superlative degree, although in general her writings are not considered to be (at least explicitly) Catholic.

- Letter n. 43, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- Letter n. 250, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf, ‘On Fairy Stories,’ (HarperCollins Publishers: London, 2001), p. 66. See also Holly Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography (Word on Fire Academic, Grove Village IL, 2023), especially pp. 3-12.

- Holly Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography (Word on Fire Academic, Grove Village IL, 2023), p.8.

- Ibid.

- Letter n. 142, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- Letter n. 328, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- See especially the chapter ‘Mount Doom’ in The Return of the King.

March 25, 2024

Some Holy Week Traditions of Italy

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

As impressive and imposing as the historical ceremonies of Holy Week are, there grew up around them, and with them, from the well-formed piety of the faithful, other practices which, while complementing these liturgies, give them a more local flavor. In this way, place is found for both the universality of the Catholic Liturgy and also local customs. With this background, I would like to share here some Holy Week traditions from Italy.

The first actually begins at the start of Lent. In southern Italy, wheat is planted in shallow pots and then kept in a warm room with no light. Because of these conditions, the wheat grows with a golden color, instead of the usual green. In modern times, sometimes these pots also have flowers planted in them. On Holy Thursday, these pots, called sepolcri (lavureddi in Sicilian) are used to decorate the Altar of Repose. After the conclusion of the ceremonies, the golden wheat is planted in fields as a blessing.1

Also on Holy Thursday, in certain villages, those men who had their feet washed would receive a bread wreath. In some places, such as in Calabria, dough shaped to represent the instruments of the Passion were baked onto the wreaths.

On Palm Sunday, olive branches are blessed in lieu of or together with palms. Prior to the reform of Holy Week under Pope Pius XII, the first of the five blessings was particularly for these branches.2 The text of this first prayer is as follows:

We beseech thee, O holy Lord, almighty Father, eternal God, that thou wouldst be pleased to bless and sanctify this creature of the olive tree, which thou madest to shoot out of the substance of the wood, and which the dove, returning to the ark, brought in its bill; that whoever receiveth it, may find protection of soul and body, and that it may prove, O Lord, a saving remedy, and a sacred sign of thy grace. Through, &c.3

The second, third (which says that “the olive branches proclaim, in some manner, the coming of a spiritual unction”4), and fifth prayers refer to both palm and olive branches. The focus of the fourth prayer is the olive branch, although the branches of other trees are mentioned:

O God, who by an olive branch didst command the dove to proclaim peace to the world; sanctify, we beseech thee, by thy heavenly benediction, these branches of olives and other trees; that they may be serviceable to all thy people unto salvation. Through, &c.5

In the same spirit of this prayer, again in certain villages, if there were any major disputes (such as siblings not speaking to each other) one of the parties could take one of these blessed olive branches after Mass and go the house of the other party. He would then offer the olive branch as way of signifying his desire for peace. If the branch was accepted, peace was established between them, and the dispute was never to be mentioned again. This was a public proposition of peace and reconciliation, similar to that done by Byzantine Christians at the start of Lent, but here a literal olive branch is extended. The hope was that peace could be restored before the Easter Season.

There is also a particular tradition common to the region of Campania, where the olive branches are decorated, including with treats. These olive branches are typically given as gifts to family and friends.

This tradition is particularly strong in the town of Sorrento, on the bay of Naples. In this town they adorn the olive branches with caciocavallo cheese, little salamis, and colored ribbons. There is also the particular tradition of making palme di confetti, artificial twigs or saplings, and also baskets, decorated with treats called confetti or Jordan almonds, which are sugar-covered almonds. According to pious tradition, in the sixteenth century, the town was threatened by a Saracen fleet on one Palm Sunday. The faithful had taken refuge in the cathedral church and prayed for deliverance. The priest, already vested for the ceremony, proceeded with the blessing of olive branches. The second blessing from the Missal of Pius V, it should be noted, asks that where these blessed branches are that God’s “right hand may preserve from all adversity and protect those that have been redeemed by our Lord Jesus Christ thy Son.”6 Perhaps this prayer was in use at this time in Sorrento. In any case, during the blessing, in response to their prayers and possibly also due to the power of the sacramentals recently blessed, a storm broke out and the ships were sunk. There was, according to the account, only one survivor, a young slave girl. She made it to shore and, in thanks to God for saving her both from death and slavery, embraced the Catholic Faith. She was found by a fisherman and led to the cathedral where she was welcomed by the townsfolk. In gratitude, she offered the confetti she was carrying on her which were distributed among those gathered. Until this time, the confection was unknown in the area. With the memory of this event, these artificial palme di confetti are made and blessed on Palm Sunday together with natural olive branches.7

As was said at the beginning of this article, practices such as these complement the universal Liturgy, allowing for local expression. May these practices, formed under the wings of the Liturgy, as it were, by our Catholic forefathers, be restored where they have fallen into neglect, preserved where they are still practiced, and adopted/adapted where proper. For they are also treasures of the Church.

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX. Thanks are owed to Mr. Patrick A. O’Boyle, Esq., SMOCG, for his contributions.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

-

- The Italian Apostolate of the Archdiocese of Newark is reviving this practice.

- In the Holy Week promulgated by Pope Pius XII, only one prayer, which was previously the fifth, is used for the blessing of the palms and possibly the branches of olive and other trees, depending.

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, vol. 6 (Passiontide and Holy Week). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), p. 208.

- Ibid., p. 209.

- Ibid., p. 210.

- Ibid., p. 209.

- More information can be found on articles online here, here, here, here, and here.

March 24, 2024

Thoughts on the Cabrini Movie

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

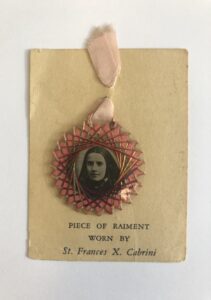

On the Saturday evening of its opening weekend, I took the parish’s Young Adult group to see the Cabrini movie. I brought along with me a second-class relic of Mother Cabrini which once belonged to my grandparents. When I asked my mother about the relic, she said that she remembers a daytrip taken one summer when she was little. She and her family – great-grandmother, grandmother, aunts, uncles, cousins, etc. – traveled from their home in New Jersey to the Cabrini Shrine in New York. Perhaps, my mother suspects, the relic came from this visit. I can only surmise what having this relic must have meant to my Italian-American ancestors. For my mother’s mother’s family is from the town of Cerami in Sicily, while her father’s side is from different communities in the south-eastern part of Italian peninsula. Not too long before the events depicted in Cabrini, southern Italy and Sicily were an independent kingdom which was unjustly invaded and then incorporated into the newly-formed Kingdom of Italy. Prior to this “unification,” the majority of emigration was from the north. But afterwards, no doubt due to the conditions which followed “unification,” there was mass emigration from the south and Sicily. Although she was from the north, it was primarily these immigrants from the south and Sicily whom Mother Cabrini served in New York. So then, not only did I go to see a movie about the first canonized American citizen, but also to see a portrayal of how my mother’s people, how my people – though not necessarily members of our family – were treated when they first arrived in these United States. A part of American history which is perhaps not well-known.

After the movie was over, I was asked what I thought about the movie by the Young Adults. I told them, at the time, it was a lot to process, but in a good way. In the hallway outside of the theater, I shared the relic with the Young Adults and then gave them a blessing before we departed.

As I continued to process my experience of the movie, I settled on the following. First, and most importantly, I do not believe I have ever felt the same after watching any other movie. There was calm, a peace, a quiet joy or happiness. Trying to place the movie among others which might be like it, I settled on Gettysburg or Gods and Generals. This, of course, should be taken with a grain of salt as I am not a film critic by any stretch (and it has been a while since I have seen these movies). But, as of the writing of this article, Cabrini stands with a 91% critics’ score and a 98% audience score (based on over 1,000 audience reviews) on the Rotten Tomatoes website. In my opinion, for what it is worth, to call this a “good movie” would not do it justice.

It does seem, however, that there is a somewhat negative reception of this movie among Catholics due to disappointment over the perceived lack of prayer, Catholic spirituality, and God. Responding to this criticism, I would start by saying that I think it is important to keep in mind what this film actually is. It is distributed by Angel Studios which is, if we were to assign a religious tag to it, Mormon. The movie was intended for a general viewership not a specifically Catholic one, unlike movies offered by EWTN or other such outlets of Catholic media. It is a movie about Catholics, but not a “Catholic movie,” and it was never intended to be. It is a movie about a Catholic saint, but not a “saint movie,” and it was never intended to be. It was never intended to be a Song of Bernadette, a Reluctant Saint, or a Passion. We should not hold this movie to a standard it was not trying to meet.

Additionally, I think it is providential that the movie came out on the Friday of the Third Week of Lent. The Gospel of the day is the account of Our Lord and the Woman at the Well (John 4:5-42). Our Lord did not begin the conversation by saying “I am the Christ and you are a sinner.” Rather, He began by saying something more innocuous – “Give Me to drink” of the water of the well. Then, from this beginning, He went deeper. I think this movie is something similar – it is only the beginning of the conversation, a conversation which can, and hopefully will, go deeper.1 But, if it started too deep, if it was too heavy-handed, so to speak, it would most likely put folks off.

It should also be noted that the movie is not completely void of any references to God or spirituality. A Priest is shown carrying around what I assume is his breviary. There is a funeral procession. Religious images are seen the backgrounds. Mother Cabrini and her daughters are shown praying grace, in Latin, before eating and, when she is in Rome, she is shown praying in a chapel. She also makes references to/quotes Scripture (such as Philippians 4:13), even if the references are subtle. I think that this is the case with the movie overall – the presentation of Catholicism is subtle, being expressed as a major part of the warp and weft of the characters’ lives without calling undue attention to itself. The presentation, then, is not heavy-handed, which goes back to the point considered in the preceding paragraph.

When I recommended seeing Cabrini, either in person or on the Ask A Priest Live program, before I had seen the movie, I did state that I had heard that her spiritual life was downplayed, but that the movie should still be seen. Now, after having seen the movie for myself, I even more whole-heartly recommend seeing it, but with proper expectations – that is, not holding this movie to a standard it was never trying to meet, keeping in mind the actual target audience, and not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good – so that it can be appreciated for what it is.

Mother Cabrini, Pray for us!

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

- Further and deeper discussion can be aided by using additional materials such as those made available by Sophia Press (here, here, and here).

March 13, 2024

“The True, The Good, and the Beautiful” in FSSP Nigeria – Interview with Fr. Van Der Putten

Amidst our own personal and national hardships, we can easily forget our fellow FSSP parishioners in other parts of the world. Don’t miss the latest interview with Fr. Angelo Van der Putten, the head of the FSSP’s Nigerian mission Nne Enyemaka in Umuaka. Father gives a candid and somewhat sobering assessment of the mission’s latest successes but also intense challenges in a nation troubled by corruption and violence. The entire interview can be read on our Mission Tradition site. –ed.

Mission Tradition: Father, thank you for making time to speak with me. What’s the latest news from your apostolate?

Father Van der Putten: The most exciting news is from our school. As you know, we started a school in September. We rented a building for the girls’ school because we don’t have anything built yet, and we engaged some Sisters from the Franciscans of the Immaculate to teach. For the boys, we added on a room to one of the big buildings here in the parish compound, and we have several men with degrees teaching.

We recently purchased about two and a half acres of land to expand our facilities. To purchase land here is quite an extraordinary feat because it’s owned by about 20 different people who don’t have any survey markers or anything. They’ll just look at a tree and say, “That was my tree, so the property line goes there.” And then they argue about it.

So it has taken us over six months to get this piece of land. But we bought it for the Sisters so that we can build them a convent, and then a girls’ school. That’s the project we’re working on now. We’ve just about finished putting an eight-foot cement wall all the way around it. It’s about 1,000 feet of walling, and we bought razor wire to go on the top of it because we want to protect the Sisters from any possible harm. We hope to have the convent itself built before October. That’s going to be our “summer project.”

MT: That’s great news. What’s the economic situation in Nigeria?

Father VdP: The economic crisis in this country is beyond imagination. The biggest problem is inflation. Six months ago a bag of cement cost 3,500 naira. Today it costs 11,500 naira. That’s triple the price. The price of food has also doubled recently. And yet a federal employee’s monthly salary is 50,000 naira. He can buy four bags of cement in a month, but that’s all he can buy. He can’t eat because a bag of rice costs 55,000 naira. It’s totally insane.

When I got here 10 years ago, the naira traded at 168 to the dollar. Today, it’s 1,550 to the dollar. For me, it’s not such a hardship because we survive off the dollars that Americans send us. But the local people barely survive. The price of food doubles, the price of cement triples. They’re not even living from hand to mouth anymore because their salaries simply don’t cover the basics. I don’t know how they live. It’s astounding to me how people are even surviving. I know that many people eat very plainly, with lots of cassava and such. But even that food has doubled in price.

The local currency is crashing. Something has to give, but nobody knows what can give because the government is so indescribably corrupt. They don’t care anything about the people. The corruption will not stop, the stealing will just not stop.

Read more on the Mission Tradition website.

March 5, 2024

Audience with Pope Francis

The FSSP’s international headquarters in Fribourg has released the following statement:

Official communiqué of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter – Fribourg, March 1st, 2024.

Following a request from the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, Pope Francis invited Fr. Andrzej Komorowski, Superior General of the FSSP, to meet with him. He received him in private audience at the Vatican on Thursday, February 29, 2024, accompanied by Fr. Benoît Paul-Joseph, Superior of the District of France, and Fr. Vincent Ribeton, Rector of St. Peter’s Seminary in Wigratzbad.

The meeting was an opportunity for them to express their deep gratitude to the Holy Father for the decree of February 11, 2022, by which the Pope confirmed the liturgical specificity of the Fraternity of St. Peter, but also to share with him the difficulties encountered in its application. The Pope was very understanding and invited the Fraternity of St. Peter to continue to build up ecclesial communion ever more fully through its own proper charism. Fr. Komorowski informed the Holy Father that the decree of February 11, 2022 had been given on the very day of the Fraternity of St. Peter’s consecration to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, on the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes. The Holy Father hailed this coincidence as a providential sign.

March 1, 2024

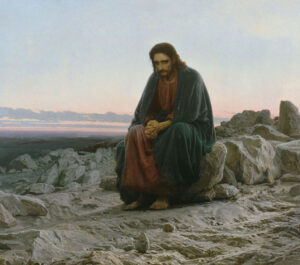

The 40 Days of Lent

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

The Gospel for the First Sunday of Lent is St. Matthew’s account of Our Lord’s 40-day fast in the desert and His subsequent temptation by the devil (4:1-11). This is a fitting Gospel to have proclaimed on the solemn inauguration of Lent (which officially started the Wednesday previous) as Lent, the Church’s own 40-day period of fast, is patterned on the fast recounted in this Gospel pericope. Our Lord’s fast was itself prefigured by the 40-day fasts of Moses (Exo 24:12-18) and Elias (3 Kin 19:3-8), the accounts of which are read a few days following this Sunday, on Ember Wednesday of Lent.

But what is the significance of 40 days? According to Dr. Nathanael Schmiedicke’s Handy Guide to Biblical Numerology, the number 40 “is often used in connection with a time of trial and preparation for a new stage in Man’s relationship with God.” This is certainly true in the case of Moses, who, after his 40-day fast, received from God revelation concerning the covenant and divine worship. This meaning of the number 40 can also be applied to the 40 days and nights of rain which caused the Flood, after which mankind began anew, as it were, and the 40 years of the Hebrews wandering in the desert, after which the new generation undertook to conquer the Promised Land, a task which the preceding generation refused. Our Lord’s preaching, which set the foundation for the New and Everlasting Covenant between God and His Faithful, was inaugurated after His 40-day fast. In this sense, then, the Church’s fast can be seen as a period of “trial,” as 40 days of fasting is difficult, but also as the “preparation for a new stage in Man’s relationship with God,” for by this fast one should subdue the rebellious flesh and enter into a new, that is improved, relationship with God.

St. Gregory the Great, in a sermon, noted that the fast of Lent can be seen as serving as a tithe of the year to God.

The Creator of all things took no food whatever during forty days. We also, at the season of Lent as much as in us lies afflict our flesh by abstinence. The number forty is preserved, because the virtue of the decalogue is fulfilled in the books of the holy Gospel; and ten taken four times amounts to forty. Or, because in this mortal body we consist of four elements by the delights of which we go against the Lord’s precepts received by the decalogue. And as we transgress the decalogue through the lusts of this flesh, it is fitting that we afflict the flesh forty-fold. Or, as by the Law we offer the tenth of our goods, so we strive to offer the tenth of our time. And from the first Sunday of Lent to the rejoicing of the paschal festival is a space of six weeks, or forty-two days, subtracting from which the six Sundays which are not kept there remain thirty-six. Now as the year consists of three hundred and sixty-five, by the affliction of these thirty-six we give the tenth of our year to God.1

Before Ash Wednesday and the following days were added to Lent (bringing the number of fasting days up 40), the Lenten season started on the First Sunday, giving 36 fasting days. These 36 days were seen as a tenth of the 365 days of the calendar. These 36 days, a tenth of the year, were offered to God as a tithe (which is the giving of a tenth of some good). Perhaps this idea of Lent being a tithing of the year motivated the choice of the First Lesson of Ember Saturday in Lent (Deu 26:12-19) which begins: “When thou hast made an end to tithing all thy fruits, thou shall speak thus in the sight of the Lord thy God…” This tithing interpretation can still hold more-or-less, even though now 40 days are being offered instead of 36. The Holy Pontiff also notes that 40 can represent the 10 Commandments being fulfilled by the 4 Gospels (10*4=40)

In his 55th Letter (n. 28), St. Augustine explains that 40 symbolizes the labor of this life.

Now, in what part of the year could the observance of the Fast of Forty Days be more appropriately placed, than in that which immediately precedes and borders on the time of the Lord’s Passion? For by it is signified this life of toil, the chief work in which is to exercise self-control, in abstaining from the world’s friendship, which never ceases deceitfully caressing us, and scattering profusely around us its bewitching allurements. As to the reason why this life of toil and self-control is symbolized by the number 40, it seems to me that the number ten (in which is the perfection of our blessedness, as in the number eight, because it returns to the unit) has a like place in this number; and therefore I regard the number forty as a fit symbol for this life, because in it the creature (of which the symbolic number is seven) cleaves to the Creator, in whom is revealed that unity of the Trinity which is to be published while time lasts throughout this whole world — a world swept by four winds, constituted of four elements, and experiencing the changes of four seasons in the year.

According to Augustine, one arrives at the number 40 first by considering that the creature (which can be represented by the number 7 due to the seven days of creation) seeks to be united to the Creator (which can be represented by 3 for the Persons of the Trinity). The unity of 3 and 7 is 10. This unity between creature and Creator should be universal, which can be represented by the number 4 as the four winds, the four elements (see below), and the four succeeding seasons of the year indicate the whole world. 10 spread 4 times over gives 40 (10*4=40). The Saint notes that this season of 40 days occurs before the 50 days of Easter, which itself represents the future life of beatitude. Therefore, the labors of the 40 days of Lent represent the entirety of the labors of this life, which, God willing, will give place to the period of eternal rest, symbolized by the 50 days of Easter.

This understanding of Augustine also explains why Our Lord remained with His Apostles for 40 days after His Resurrection. Before His Ascension, Our Lord told His Apostles, “And behold I am with you all days, even to the consummation of the world” (Mat 28:20). As 40 represents this life, the 40 days between His Resurrection and Ascension symbolize His presence with the Church until the end of time. One should not be disturbed by the days after Easter having multiple symbolic meanings. It is perfectly acceptable for passages of Scripture, and thus also the Church’s Liturgy, to have several non-contradictory meanings.

It is worth noting that in another place, namely in his Harmony of the Gospels (II, 4, 9), St. Augustine explains that 10 is found by summing what mathematics would call today the first four positive whole numbers (1+2+3+4=10) (this means that 10 is a triangular number, just like 153, the number of Aves in a full Rosary). And, of course, 4 times 10 is 40. From here, one can then inquire into the meaning of 10 and 4, which will provide results similar to those presented above. St. Augustine also explains that just as St. Matthew’s genealogy (1:1-16) has Our Lord descending to us by the number 40 (40 men, not including Our Lord, are listed), so do the Faithful rise to Our Lord by the number 40 (40 days of fasting).2

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Commentary on St. Matthew (n. 313), echoes one of the reasons given by St. Gregory as to why the fast should last 40 days.

And one should know that this number is prefigured in the Old Testament in Moses and Elias (Exod 24:18: 1 [3] Kgs 19:8). And a mystery is hidden in this, because such a number arises from ten multiplied by four. The ten signifies the law, because the whole law is contained in ten precepts. The four signifies the composition of the body, because the body is composed out of four elements. Since therefore we transgress the divine law at the suggestion of the body, it is just that we afflict our body for forty days.

According to the medievals, the human body was composed out of the four elements – earth, water, air, and fire. Even though this is incorrect, perhaps this passage of St. Thomas can be interpreted in the context of modern science. To begin with, these four elements can be seen as corresponding to the four primary states of matter – solid, liquid, gas, and plasma – by which material creation is primarily composed. Matter in each of these states can also be involved in sin. For example, sinning against one’s neighbor would involve the solids, liquids, and gases which composed the neighbor (and the self). Idolatry involving stars would involve matter in the state of plasma. St. Thomas’s explanation can be re-expressed, then, as follows:

The ten signifies the law, because the whole law is contained in ten precepts. The four signifies material creation, because material creation is primarily composed out of matter in four states. Since therefore we transgress the divine law by means of material creation, it is just that we afflict our body for forty days.

Even if some may find this reinterpretation of St. Thomas not overly convincing, this takeaway is still valid – Lent is, at its heart, a season of reparation for sin.

In answer to the question posed at the start, there are complimentary ways of understanding the significance of the fast of Lent being 40 days. These understandings build on each other to reveal the depth of a season which has its own worth apart from its purpose as a preparation for the celebration of Easter. Knowing this, may the Faithful enter into and keep this season with a renewed and deeper appreciation.

Fr. Wiliam Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

- Hom. in Ev., 16, 5 (according to the Catena Aurea).

- See Durandus, Gulielmus. Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, VI, XXXII, 2. The reference of Augustine is cited as De Consec. dist. 5. Jejunium. Durandus also associates the 46 years the Second Temple was being renovated (Joh 2:20) to the 46 totals days of Lent (which traditionally would have all been days of abstinence, so Lent would have been 46 days of abstinence and 40 days of fasting). Just as 46 years were used unknowingly to renovate and beautify the Temple for the coming of the Messiah, so should the Christian knowingly spend 46 days in abstinence and good work beautifying the soul with virtue in preparation for the celebration of Messiah’s Resurrection (VI, XXVIII, 3).

February 18, 2024

FSSP Renewal of Consecration 2024

In the midst of uncertainty in the Church and the world, the Fraternity of St. Peter will be renewing its consecration to the Blessed Virgin Mary on February 11th. Our future remains uncertain after the motu proprio Traditionis custodes of July 2021, and there is no better place for us to go than to our Mother. Please join the members of the FSSP in praying a novena to Our Lady from February 2nd, the Feast of the Candlemas, to February 11th, the Feast of Our Lady of Lourdes. The novena consists of at least one decade of the Rosary daily followed by the Memorare. The intention is for the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter and our mission in the Church. May God reward you!

February 1, 2024

The Sacramentals of St. Blaise Day

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

Many Catholics are no doubt familiar with the blessing of throats performed on the feast of St. Blaise (February 3rd), one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, who miraculously healed “a boy, whose life was despaired of by the physicians, on account of his having swallowed a bone, which could not be extracted from his throat,” as it is stated in his biography from Matins.1 The blessing involves having blessed candles joined in the shape of a cross held to the throat while the Priest recites the following:

By the intercession of St. Blaise, bishop and martyr, may God deliver you from every malady of the throat, and from every possible mishap; in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, + and of the Holy Spirit. ℟. Amen.2

The use of candles as part of this blessing may have its origin in the following account: “Blaise met a poor woman whose only pig had been snatched up in the fangs of a wolf but at the command of the bishop the wolf restored the pig alive to its owner. The woman did not forget the favor, for later, when the bishop was languishing in prison, she brought him tapers to dispel the darkness and gloom.”3

But this blessing of throats is not the only special sacramental associated with the feast of St. Blaise. To begin with, one might think that these candles used in the throat blessing were blessed the day before, the Feast of Candlemas, but these candles have a unique (and long) blessing of the day applied to them. This blessing is as follows:

℣. Our help is in the name of the Lord.

℟. Who made heaven and earth.

℣. The Lord be with you.

℟. And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

God, almighty and all-mild, by Your Word alone You created the manifold things in the world, and willed that that same Word, by Whom all things were made, take flesh in order to redeem mankind; You Who are great and immeasurable, awesome and praiseworthy, a worker of marvels. Hence in professing his faith in You the glorious martyr and bishop, Blaise, did not fear any manner of torment but gladly accepted the palm of martyrdom. In virtue of which You bestowed on him, among other gifts, the power to heal all ailments of the throat. And now we implore Your majesty that, overlooking our guilt and considering only his merits and intercession, it may please you to bless + and sanctify + and impart Your grace to these candles. Let all men of faith whose necks are touched with them be healed of every malady of the throat, and being restored in health and good spirits let them return thanks to You in Your holy Church, and praise Your glorious name which is blessed forever; through Christ our Lord.

℟. Amen.

The candles are then sprinkled with holy water.4

The reference to Our Lord’s incarnation at the beginning of this blessing has a special significance in this context as the candle is seen as being a sign of the Incarnate Lord. In particular the wax is seen as representing His Body, the wick, His Soul, and the flame, His Divinity.

Lastly, there is the special blessing of bread, wine, water, and fruit in honor of the Saint for the relief of throat ailments. The blessing is as follows:

℣. Our help is in the name of the Lord.

℟. Who made heaven and earth.

℣. The Lord be with you.

℟. And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

God, Savior of the world, Who consecrated this day by the martyrdom of blessed Blaise, granting him among other gifts the power of healing all who are afflicted with ailments of the throat; we humbly appeal to your boundless mercy, begging that these fruits, bread, wine, and water brought by Your devoted people be blessed + and sanctified + by Your goodness. May those who eat and drink these gifts be fully healed of all ailments of the throat and of all maladies of body and soul, through the prayers and merits of St. Blaise, bishop and martyr. We ask this of You Who live and reign, God, forever and ever.

℟. Amen.

The items are then sprinkled with holy water.5

While this blessing is only to be performed on the feast of St. Blaise, the blessed items can be saved and consumed as needed throughout the year.

In addition to receiving the yearly blessing of throats, the faithful, especially those who are prone to ailments of the throat, are also encouraged to take advantage of this unique blessing of bread, wine, water, and fruit. Of course, it is best to coordinate this with one’s priest ahead of time.

Fr. Wiliam Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, vol. 4 (Septuagesima). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), p. 236.

- Latin original Rituale Romanum, Titulus IX – Caput 3, 7; English adopted from the Weller translation of the Roman Ritual provided online by EWTN.

- From the Weller translation of the Roman Ritual provided online by EWTN, “Chapter II: Blessings for Special Days and Feasts of the Church Year, 10.”

- Rituale Romanum, Titulus IX – Caput 3, 7; English adopted from the Weller translation provided online by EWTN.

- Rituale Romanum, Titulus IX – Caput 3, 8; English adopted from the Weller translation provided online by EWTN.

January 29, 2024