‘I am a Christian…and in fact a Roman Catholic’

by Fr Brendan Boyce, FSSP

The 20th century, as every competent analysis concludes, was largely one of marked – and deleterious – upheaval at almost every level of human experience: social, political, technological, military and, yes, religious. And yet, amidst the horrors of the age, like a lamp shining in the darkness, this same century saw the flourishing of Catholic literary endeavour of, at times, a most poignant expression.

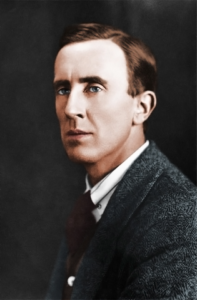

There are Catholic literary giants of the 20th century who need no introduction; individuals such as G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc and Evelyn Waugh, to name but a few. However, the person of J.R.R. Tolkien,1 while generally acknowledged to have been a great author, is not often associated in the same way as these others as a particularly Catholic author.2

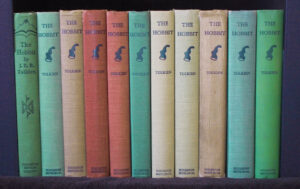

In one sense, this is understandable. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, for example, does not proclaim itself to be Catholic, at a surface reading, in the same way as Brideshead Revisited; nor even as generically Christian, as does C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. But all this is to put the cart before the horse, because what should be first in our gaze on the works of Tolkien is the man himself.

And Tolkien was nothing if not a (very devout) Catholic. His own words bear this out (to give two examples among many); firstly in a letter written to his son Christopher in 1941, in the midst both of the Second World War and the writing of what was to become the Fellowship of the Ring:

Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament….There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth, and more than that: Death: by the divine paradox, that which ends life, and demands the surrender of all, and yet by the taste (or foretaste) of which alone can what you seek in your earthly relationships (love, faithfulness, joy) be maintained, or take on that complexion of reality, of eternal endurance, which every man’s heart desires.3

Just over 20 years later in 1963, writing again to the same son, Tolkien displays once more the great depth of his faith with regard to the Blessed Sacrament:

The only cure for sagging of fainting faith is Communion. Though always Itself, perfect and complete and inviolate, the Blessed Sacrament does not operate completely and once for all in any of us. Like the act of Faith it must be continuous and grow by exercise. Frequency is of the highest effect. Seven times a week is more nourishing than seven times at intervals. I witnessed (half-comprehending) the heroic sufferings and early death in extreme poverty of my mother who brought me into the Church; and received the astonishing charity of [Father] Francis Morgan. But I fell in love with the Blessed Sacrament from the beginning – and by the mercy of God never have fallen out again…4

Other examples abound of Tolkien’s firm adherence to the Faith throughout his life, from his devotion to Our Lady and attendance at daily Mass, to the testimonies of his family and life-long friends to his deep faith. Allowing this representation to stand, then, the question of the impact of his faith on the writing of his works may be considered.

Tolkien himself gives us the clearest insight into answering the question. In his view, it was impossible for an author to ‘disentangle’ faith and art. Tolken felt deeply that the writing of fantasy (and by extension all literary output) is a natural human activity and right. This conviction was based on his adherence to Catholic teaching (and biblical truth) that human persons are made in the image and likeness of God. Further to this is that since God creates, one would unquestioningly be less than human if one were not to express the ‘creative’, or ‘sub-creative’, side of one’s nature. In his important essay, On Fairy Stories, Tolkien declared: ‘…we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.’5

Holly Ordway, in her impressive and very readable work Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography, notes that art necessarily reflects something of the artist’s most deeply held beliefs, at least at some level, however subtle or implicit. For Tolkien, faith was not merely a set of superficial opinions, but something integral to his real character – and to his own self-understanding as an author of fiction.6 She continues: ‘So, it follows that if we are to understand and appreciate Tolkien’s writings to the fullest degree, we need to come to an understanding of what he himself identified as central to his identity: his faith, which could not be disentangled from his art.’7

In considering, then, the works of Tolkien, such as The Lord of the Rings, these things must be borne in mind. Further to that, we have Tolkien’s own view upon these matters, written to his friend Robert Murray SJ, who had commented upon elements of the work itself, with a particularly Catholic point of view:

The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.8

This is the sense, then, in which we must see The Lord of the Rings as a ‘fundamentally religious and Catholic work’, because it is in the intention of the author. Not for Tolkien the unabashed allegory of the Narnia Chronicles; nor the ‘realism’ of a Brideshead Revisited. His work is imbued in a manner redolent of that quiet, unhurried, gentle way of the working of grace in its harmony with matters of the Faith. One of his avid readers perhaps captures this best: ‘You…create a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp.’9

Greater writers than I, in works more mature than this, have delved into discussions of what is Catholic in The Lord of the Rings; but let us at least allude to some of these elements here. They range from the simple – such as the Fellowship departing from Rivendell on Christmas Day, or, if it is not giving too much away, the fall of Sauron on the Feast of the Annunciation/Incarnation – to the more profound, such as the roles of heroic self-denial and mercy and the presence and effect of lembas, the Elvish way-bread which is evocative of the Eucharist, particularly in its effects (feeding the will of those who rely upon it alone10). In the words of characters, also, we may discern sometimes more fundamentally religious and Catholic sentiments, such as in the inn at Bree, where Aragorn, despite his high destiny, states his willingness to give his life to protect Frodo; or at the Council of Elrond, in Frodo’s act of faith in being prepared to take the ring, though he does not know the way; or, most strikingly, Gandalf’s words to the Balrog upon the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, as one good angelic figure faces down a fallen angel, that he is (for those who have ears to hear) the servant of the Secret Fire (the One God) and that the dark fire of Udûn (hell) shall not avail the balrog. Beyond this work too, especially in The Silmarillion and other early (posthumously published) works, the influence of his faith may be even more readily discerned.

What matters in all of this is that we are not afraid to name a work Catholic, and to understand that it is Catholic, when its author is Catholic and when this author calls his work Catholic, even when that work may not be to our taste, or even when that work may be in a genre not necessarily ‘recognised’ as Catholic. For Catholicism has always found expression in various forms of art, from visual art to music to the written word, and within these modalities are various forms, which in their own unique way grant access, to those who are disposed, to the great truths of the Faith. We should see The Lord of the Rings, among Tolkien’s other works, as firmly (if uniquely) ensconced within the Catholic literary tradition of the 20th century, as a signal contribution to the light of our beautiful faith within the darkness of our modern age. Suggested further reading:

Suggested further reading:

- B.J. Birzer, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle Earth (Tempus, Stroud, UK, 2006).

- L. Coutras, Tolkien’s Theology of Beauty: Majesty, Splendor, and Transcendence in Middle-earth (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2016).

- A. Freeman, Tolkien Dogmatics: Theology through Mythology with the Maker of Middle-earth (Lexham, Bellingham WA, 2022).

- P. Kerry and S. Miesel, Light Beyond all Shadow: Religious Experience in Tolkien’s Work (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Madison WI, 2011).

- H. Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography (Word on Fire Academic, Grove Village IL, 2023).

- J. Pearce, Tolkien: Man and Myth (Harper Collins, London, 1998).

- J.R.R. Tolkien, The Nature of Middle-Earth (ed. C. Hostetter) (Harper Collins, London, 2021), especially Appendix I, ‘Metaphysical and Theological Themes’, pp. 401-412.

Fr Brendan Boyce FSSP was born and raised in New Zealand (also known as Middle-earth). He is currently posted to the FSSP apostolate in Canberra, Australia, but remains hopeful of one day being sent, like Gandalf, back to Middle-earth.

- The title of this article is taken from Tolkien’s Letter n. 213 (J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter n. 213, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter, [HarperCollins Publishers: London, 2006].)

- Another example of this would be the American author Flannery O’Connor (+1964), whose faith informed her writing to a superlative degree, although in general her writings are not considered to be (at least explicitly) Catholic.

- Letter n. 43, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- Letter n. 250, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf, ‘On Fairy Stories,’ (HarperCollins Publishers: London, 2001), p. 66. See also Holly Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography (Word on Fire Academic, Grove Village IL, 2023), especially pp. 3-12.

- Holly Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith, A Spiritual Biography (Word on Fire Academic, Grove Village IL, 2023), p.8.

- Ibid.

- Letter n. 142, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- Letter n. 328, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- See especially the chapter ‘Mount Doom’ in The Return of the King.

March 25, 2024