Marcus Tullius Cicero and the Traditional Latin Mass

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

As the name suggests, the Traditional Latin Mass is mostly prayed in Latin. While there is some Hebrew and Greek, the majority of the ceremony is carried out in the Latin language. But to say that the Traditional Latin Mass is in Latin does not completely capture the state of things, as there are varieties in the Latin used. For example, the readings (Lessons, Epistles, Gospels) are taken from St. Jerome’s [d. A.D. 420] translation of the Sacred Scriptures (the Vulgate), while the chants (Introit, Gradual, Alleluia, Offertory, Communion, etc.) are drawn from Latin translations of Holy Writ which pre-date Jerome’s work.1

The Latin of the Orations (Collects, Secrets, and Postcommunions) is also noteworthy in that these prayers utilize a specialized vocabulary, setting it apart from the Latin with which one would normally converse.2 Additionally, the arrangement of the words themselves are not without consideration. Word placement at the end of clauses follows certain patterns which can be traced back to a Roman oratory style first used by Marcus Tullius Cicero, a renowned Roman orator [d. 43 B.C.], drawing from patterns used by the Greeks.3

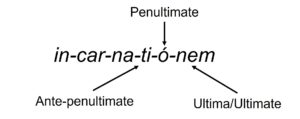

In order to understand how these patterns are present in the Orations, an understanding of spoken Latin must come first. In spoken Latin, only the second-to-last (penultimate) or third-to-last (ante-penultimate) syllable receives stress. In some cases, stressing the proper syllable distinguishes between words with the same spelling. Without knowing which syllable is stressed, and without context, Maria could be either Mary (María) or seas (Mária). When Latin is written, the stressed syllable is marked by an accent to aid the reader.

The oratory patterns direct how words are to be arranged at the end of clauses based on where the words are stressed/accented for rhetorical weight. This also sets the rhythm of the prayers. There are four agreements, each called a Cursus.4 The Postcommunion of the Feast of the Annunciation, which is also the prayer used at the conclusion of the Angelus, will serve as the basis for exploring three of the Cursus.5

Grátiam tuam, quǽsumus, Dómine, méntibus nostris infúnde; ut, qui, ángelo nuntiánte, Christi Fílii tui incarnatiónem cognóvimus, per passiónem eius et crucem, ad resurrectiónis glóriam perducámur. Per eúndem Dóminum nostrum Iesum Christum Fílium tuum, qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitáte Spíritus Sancti, Deus, per ómnia sǽcula sæculórum.

In the Cursus Planus, “a word accentuated on the penultimate syllable is followed by a word of three syllables also accentuated on the penultimate syllable; that is, the accents are placed on the second and fifth syllables from the end.” This is seen in the Postcommunion as follows: méntibus nó-stris in-fún-de;.

In the Cursus Tardus, “a word accentuated on the penultimate syllable is followed by a word of four syllables accentuated on the ante-penultimate syllable, that is, accents on the third and sixth syllable from the end.” The phrase in-car-na-ti-ó-nem cog-nó-vi-mus, follows this Cursus in the Postcommunion.

The Cursus Velox is “the most solemn and also the most elegant: a word of three syllables or more accentuated on the ante-penultimate is followed by a word of four syllables accentuated on the penultimate; that is, accents on the second and seventh syllable from the end.” Two examples of this type can be found in the Postcommunion: gló-ri-a per-du-cá-mur. and saé-cu-la sae-cu-ló-rum. As saécula saeculórum is present at the conclusions of the prayers at Mass, this Cursus is pervasive.

Lastly, there is the Di- or Tri-spondiac Cursus where the accents are “on the second and sixth syllables from the end.” There are not examples of this type in the Postcommunion prayer, but they can be found in the Collects of Easter (mór-te, re-se-rá-sti:) and of Pentecost (il-lu-stra-ti-ó-ne do-cú-is-ti:).

The objection might be raised that Christian prayer should be free from any “pagan contamination” and that making use of these patterns pollutes what should be pure Christian worship. Here, the principle explained by St. Augustine in his De doctrina Christiana should be applied.6 According to the Saint, all that is true, good, and beautiful belongs by right to the True Church of God, regardless of its origin. He points to how the Hebrews used the gold provided to them by the Egyptians as they departed to make the Ark of the Covenant and the other liturgical items commanded by God. If such can be done with pagan gold, Christians can surely use all else which is true, good, and beautiful in their worship, regardless of its origin. Besides, is it not fitting for Christians, when addressing God, the Supreme Being, most worthy of honor and worship, to employ high forms of language when composing public, liturgical prayer? High things for the Highest.

Now, it is not expected that the faithful will comb through their hand Missals and identify all of the Cursus contained therein or for this to be a focus of one’s attention during Mass. But it is important to know that these Cursus exist, as this knowledge, even if it is only general, will deepen the faithful’s understanding and appreciation of the treasures contained in the traditional Roman Missal.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- More recent feasts will also use a translation of the Psalms prepared during the pontificate of Pope Pius XII (A.D. 1939-1958)

- See Mohrmann, Christine. Liturgical Latin: Its Origins and Character. London: Burns & Oates, 1959.

- Cursus | Encyclopedia.com

- This is the spelling of the singular and the plural in the Latin.

- The foundation of the information for this article, along with the quotes explaining the Cursus, is drawn from Amiot, François. The History of Mass. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1959, pp. 44-45.

- Book II, Chapter 40.

May 31, 2022