Near the Apostles: the Feasts of the First Popes

Historically it is very clear–contrary to the opinion of some implacable skeptics–that St. Peter governed the Church of Rome and was martyred there, after having appointed men to succeed him in that role.

It’s well worth thinking about those men whom Peter chose to succeed him in that very first century of Christianity, as these men set the standard for that post-Apostolic Petrine office that would endure to the present day. We don’t know very much about them, but it’s important for us to know that their authority derives from that of Peter and the other Apostles.

Fortunately, the liturgy is there to help us in that regard.

As it happens, early Papal feasts form something of a repeating pattern toward the end of the Fall months: St. Linus (Sept. 23), St. Evaristus (Oct. 26), and finally St. Clement (Nov. 23). One other first-century Pope, St. Cletus, is honored on April 26th–in Spring, but still around the same time of the month.

These dates come down to us from antiquity: they first appear in the Liber Pontificalis, a chronicle of the Popes that was likely written in the 5th or 6th century but was compiled from older documents. Because not all of those older documents are extant any longer, it is debatable to what degree the dates preserved in the Liber Pontificalis go all the way back to the 1st century and reflect historical dates of martyrdom. They are, however, certainly ancient.

While the liturgical connections between the early Popes and Peter are obvious–most notably in the Mass Si diligis me–their feast days also echo a larger pattern seen in the other Apostles, which tend to cluster likewise in the 20s of each month. The Pontiffs’ feasts are very close to St. Matthew (Sept. 21), Ss. Simon and Jude (Oct. 28), St. Andrew (Nov. 30), and St. Mark (Apr. 25).

Thus, for 1500 years, the calendar has made a subtle connection between the early Popes and the whole Apostolic College.

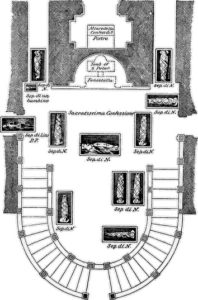

Proximity to Peter and the Apostles is a very old theme. The Liber Pontificalis states that Popes Linus, Cletus, and Evaristus were buried “near the body of the Blessed Peter”. St. Clement is a notable exception here, as he was martyred along the Black Sea.

And indeed, when the necropolis under the Vatican Basilica’s high altar was excavated in the mid-20th century, archaeologists found numerous early graves clustered around the central grave of St. Peter. These unmarked ancillary graves appear to be of poor Christians, and are likely of the second century rather than the first. Nonetheless, these burials, and the burials of subsequent Popes down the ages all the way up to John Paul II, show how proximity to an Apostle remained an important principle.

The pious Catholic is intrigued to find corroborating evidence from history or archaeology.

Yet it’s perhaps even more comforting to know that even if we did not have documents and ancient ruins to point the way, the sacred deposit of the faith preserved in the liturgy already helps us see the continuation between the Apostles and the men they appointed.

Ss. Linus, Cletus, Clement, and Evaristus, pray for us!

September 20, 2022