On Rights of Citizens, part 1

Immigration has been a hotly contested issue over the past twenty years and the more recent presidential administrations, to the point of becoming a crisis. And it can be argued that widespread illegal immigration can be tantamount to an occupation of sorts, a veritable onslaught to dismantle national sovereignty, blur borders, and establish a new and dependent (or controllable) electorate.

When we look at the Ten Commandments, we note that the first three deal with our duties to God; the last seven deal with our duties to neighbor. The latter are consequences of the first three.

At the top of our duties to neighbor is the Fourth Commandment: Honor thy father and thy mother, which is all about respect for lawful authority, beginning with one’s parents.

The family is the basic building block of a society, of a state; families comprise a state and are therefore prior to it in origin. The government is put in place to see to the true welfare of its constituents, which is called the common good. Therefore, members of a state should rightly expect their government to preserve and protect their true rights so that they can pursue temporal and eternal happiness as a whole. (Notice how God and religion are indeed constituent to common good, and that the state is not the grantor of all rights.)

The family is the basic building block of a society, of a state; families comprise a state and are therefore prior to it in origin. The government is put in place to see to the true welfare of its constituents, which is called the common good. Therefore, members of a state should rightly expect their government to preserve and protect their true rights so that they can pursue temporal and eternal happiness as a whole. (Notice how God and religion are indeed constituent to common good, and that the state is not the grantor of all rights.)

The purpose of the federal government is first and foremost to protect the rights and common good of the citizens it governs. Consequently, the state is responsible for making laws that see to the maintenance and safety of its members, as well as making due provision for the future to ensure that the state continues to exist.

If the state does its job, it has the right to expect allegiance and respect from its members. At the most fundamental level, this entails respect for internal law and external borders by all members of a state, both the governed and the governors.

Internal law sees to the smooth governance of the members. The external borders determine where the jurisdiction of the state extends, and also who benefits from the state’s protection and who does not. In other words, a state exists to provide stability for a particular human society. As a result, those who inhabit a particular state have duties towards it.

This is where the distinction between human rights and rights of citizens is of tremendous importance.

The distinction between human rights and citizen rights is based upon a relation of justice; that is, a relation of mutual obligation and dependence between a government and those governed by it.

The distinction between human rights and citizen rights is based upon a relation of justice; that is, a relation of mutual obligation and dependence between a government and those governed by it.

All in all, human rights are much broader in scope than citizen rights, as the former pertain to the rights every human being has to life, liberty, and the lawful possession of private property.

Citizen rights, however, are more specified, in that certain human rights require assistance from a specific sovereign government in order to be better realized, all in the interest of promoting the common good, to which we share responsibility, for things we cannot attain individually but collectively.

This includes greater employment opportunities for the able-bodied and able-minded, development of resources for national advancement, the creation of wealth, public safety, police, public health, and national self-defense. Citizen rights are acquired by contract with a state – a state which is determined by borders and common law – and a contract which is entered into either by birth or by choice, under which a citizen is now subject and which a citizen supports.

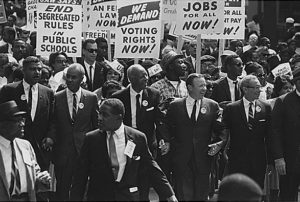

Since they contribute and since they pledge allegiance to their state – meaning they stand ready to defend it, citizens of a nation alone have rightful and just claim on the benefits from their government.

Therefore, although a state can make due provision for those who may live and work within its borders who are not citizens, it is obliged to ensure that citizens’ rights are not infringed upon by their presence, because that would upset the common good. In considering its relationship then with other sovereign states, especially for purposes of trade, a state must realize, in efforts to preserve and promote human rights for all, that its primary interest is in the protection of the rights of its citizens.

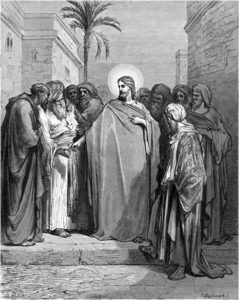

This is what Christ meant when He commanded rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s; these should never be in opposition, since what belongs to Caesar also belongs to God.

This is what Christ meant when He commanded rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s; these should never be in opposition, since what belongs to Caesar also belongs to God.

A citizen is one who is bound in justice to support the state he lives in, in return for the stability a state should provide. Those who are not citizens of a specific state do not possess any of these rights and entitlements because they are not strictly bound to support it.

So, in virtue of its duty to protect and promote the common good for those under its care and responsibility, a sovereign government has the right to know who its citizens are and also who are non-citizens living within its borders. It has the right to increase or limit the presence of non-citizens, and even certain nationalities of non-citizens for a just cause, including immigration and the process towards legal citizenry.

The citizens have a right to expect this, since they have first claim on the limited resources of a nation. They are the ones who must support the state, so the government also has the right to impose restrictions on the benefits non-citizens receive while living within its jurisdiction.

Thus a government can demand remuneration of some kind from legal non-citizens while, at the same time, extending only limited, albeit just, benefits in return.

October 28, 2020