On the Stars

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

According to the Genesis creation account, on the Fourth Day, God created the sun, the moon, and the stars:

And God said: Let there be lights made in the firmament of heaven, to divide the day and the night, and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days and years: to shine in the firmament of heaven, and to give light upon the earth, and it was so done. And God made two great lights: a greater light to rule the day; and a lesser light to rule the night: and the stars. And he set them in the firmament of heaven to shine upon the earth. And to rule the day and the night, and to divide the light and the darkness. And God saw that it was good. And the evening and morning were the fourth day. (Gen 1:14-19).

It is of great importance to note that in addition to marking the distinction between the day and the night, these heavenly bodies were also given “for signs, and for seasons, and for days and years.” As the Hebrew word translated here as “seasons” can also mean “feasts,”1 this passage indicates that God intended these heavenly bodies to play a role in the religious observances of the pinnacle of material creation, man. The role of the sun in this regard, particularly with respect to the solstices and the equinoxes, was explained previously. More recently, an explanation of the role the phases of the moon play in this regard was also presented. This just leaves the stars to be treated.

The roles of the stars when first encountered might strike some as strange as the foundation of the stars’ role is found in the 12 constellations of the zodiac. For some, the word “zodiac” immediately calls to mind the sin of astrology, but this was not the case for our Christian forefathers. For them, the constellations which comprise the zodiac were placed there by God for the sake of measuring time. The solar year was determined by the time it took the sun to traverse all 12 signs of the zodiac. That this is how Christians measured the year is attested to by William Durandus the Elder, Bishop of Mende (d. A.D. 1296), the great medieval liturgical commentator, in his Rationale Divinorum Officium (see VIII, III, 4). Additionally, the Roman Liturgical books contained a section entitled “The Year and its Parts” (De Anno et ejus Partibus) which begins:

The year comprises twelve months, or fifty-two weeks and one day; more precisely, 365 days and almost six hours; this being the time taken for the sun completely to traverse the Zodiac.2

The text then goes on to explain leap years and that the year actually falls short of the 365 days and six hours.

As the sun progresses through the zodiac, it enters, is in, and then leaves each of the constellations, dividing the year into 12 segments based on which constellation the sun is currently traversing. However, just as it was explained previously that in addition to the astronomical full moon and astronomical Spring Equinox there are the Ecclesiastical full moon and the Ecclesiastical Spring Equinox, there is also the Ecclesiastical zodiac which is the counterpart to the astronomical zodiac. But, in order to understand this, one must have an understanding of how the Roman calendar expresses the days of the month.

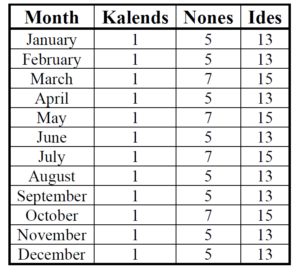

Like many ancient peoples, the early Romans used the phases of the moon to determine the months.3 The first day of the month, the Kalends, was the day of the new moon (when the first crescent of the waxing moon was visible), the Nones marked the first lunar quarter (the half moon while the moon is waxing), and the Ides, the full moon.4 On the Kalends, a pagan Roman priest, the pontifex minor, would announce the new crescent and how many days until the Nones. On the Nones, he would announce how many days until the Ides. The days between the Kalends and the Nones and between the Nones and the Ides were kept in a count-down fashion. These three days, the Kalends, the Nones, and the Ides, served as the reference days for the rest of the days of month.

As the calendar developed, the months became disassociated from the phases of the moon, but the method of determining the days within the month as well as the names for the reference days were retained.5 The Kalends still indicated the first day of the month, while the Nones was either the fifth or seventh day of the month, and the Ides the thirteenth or fifteenth day of the month, depending. Although these reference days were no longer tied to the phases of the moon, the relationship between them continued to reflect this origin. The full moon occurs “about 14 days”6 after the full moon (the Ides is on the thirteenth or fifteenth day of the month) and the first quarter around seven days after the new moon (the Nones is on the fifth or seventh day of the month). The following little poem is way of remembering how the Nones and Ides fall in each month:

In March, July, October, May,

The Ides are on the fifteenth day,

The Nones the seventh; but all besides

Have two days less for Nones and Ides.”

– Gildersleeve’s Latin Grammar

Laid out in a table, the reference days would fall as follows:

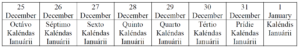

In the reckoning of the day of the month, a given day either fell on one of the three reference days, the day before one of the reference days (the Pridie), or a count back from one of the three reference days, inclusively. Yes, the days were counted backwards from the reference days. Remember, days between the Kalends and the Nones and between the Nones and the Ides were originally kept in a count-down fashion. In the calendar introduced by Julius Caesar, which was later adopted by Christians, this method for reckoning the days of the month was maintained.

By way of an example, in the current method of determining the day of the month, the Feast of the Nativity of Our Lord falls on the 25th day of December, but, in the Roman Books, it falls die octavo ante Kalendas Mensis Ianuarii, that is, on the eighth day before the first day of January, counting inclusively. The following explains visibly how that was determined.

According to this method, the Nativity of Our Lord and the Nativity of John the Baptist are celebrated on the same day of the month, the eighth day before the Kalends of January and of July respectively, although according to the currant usage one falls on the 25th and the other on the 24th.

In his Rationale, Durandus explains that each Ecclesiastical zodiac period begins on each 15th day before the Kalends (see VIII, III, 5). So, for example, during the month of March, Ecclesiastical Aries begins on the 15th day before the Kalends of April, which is March 18th (currently, astronomical Aries begins around March 21st). In the month of April, Ecclesiastical Taurus begins on the 15th day before the Kalends of May, April 17th (currently, astronomical Taurus begins around April 20th). Durandus then spends the next 12 paragraphs explaining each of the different constellations of the zodiac.

In his treatment of Aries, Durandus explains that this constellation is the start of the zodiac, as it is claimed that the sun was created in Aries and that this is the sign which the sun is in around the beginning of spring, the Spring Equinox (see VIII, III, 6). Here, Durandus, as he does throughout his work, is just echoing an earlier tradition for

many ancient Christians such as Julius Africanus believed that God created the sun on March 25th, the [original Julian observed] spring Equinox. Their reasoning was based on Scripture. In Genesis, the reason God makes the heavenly lights-the sun, moon, and stars-is to “separate the day from the night” (Genesis 1:14). It was assumed that when God divided the day and the night, He separated them evenly. Since day and night are evenly divided during the spring equinox, March 25 was believed to be the day God created the sun and the moon.7

A March 25th date for the creation of the sun would both fall within Ecclesial and astronomical Aries.

But why does this matter to Christians?

In his letter to the Emperor Marcian (CXXI), Pope St. Leo the Great (d. 461) expressed that the celebration of Easter was always to occur in the first month (Paschale etenim festum, quo sacramentum salutis humanae maxime continetur, quamvis in primo semper mense celebrandum sit8), no doubt referring back the ordinance that the Hebrew Passover was to be celebrated in “the first month” (Lev 23:5). The writings of the Jewish historian Josephus (d. ~A.D. 100) shed some relevant light onto how the “first month” is to be determined. In his Antiquities of the Jews (3.10.5), Josephus wrote:

In the month of Xanthicus, which is by us called Nisan, and is the beginning of our year, on the fourteenth day of the lunar month, when the sun is in Aries, (for in this month it was that we were delivered from bondage under the Egyptians,) the law ordained that we should every year slay that sacrifice which I before told you we slew when we came out of Egypt, and which was called the Passover.

According to Josephus, “the first month” is when the sun is in Aries, corresponding with Durandus’ claim that Aries marked the beginning of the zodiac cycle and thus the year.

While St. Leo, for his part, does not state exactly how the month he referenced is to be determined, he does indicate that Easter, according to ancient custom, can only be celebrated from March 26th (the day after an observed Spring Equinox) to April 21st (Siquidem ab undecimo kalendarum Aprilium, usque in undecimum kalendarum Maiarum, legitimum spatium sit prefixum, intra quod omnium varietatum necessitas concludatur: ut Pascha Dominicum nec prius possimus habere nec tardius9). An earlier reference to this tradition can be found in the Festal Letter of St. Athanasius for the year A.D. 349. This Letter expresses that the date of Easter for that year proposed by the church of Alexandria — after the First Council of Nicaea, the church of Alexandria was entrusted with calculating the date of Easter — was rejected by the church of Rome because it fell beyond the limits received from St. Peter (ob traditionem a Petro apostolo acceptam).10 The window provided by St. Leo of March 26th to April 21st corresponds to when the sun is, for the most part, in Aries (March 21st to April 19th astronomically or March 18th to April 16th ecclesiastically), corresponding to the determination of the “first month” given by Josephus. The occasion of this letter to Marcian by Leo was a dispute with the Bishop of Alexandria who had, again, proposed a date for Easter outside of the Roman range. Reflecting on this, Cardinal Ratzinger, in his Spirit of the Liturgy, wrote the following:

In the fifth century there was a controversy between Rome and Alexandria about what the latest possible date for Easter could be. According to Alexandrian tradition, it was April 25. Pope St. Leo the Great (440-461) criticized this very late date by pointing out that, according to the Bible, Easter should fall in the first month, and the first month did not mean April, but the time when the sun is passing through the first part of the Zodiac — the sign of Aries. The constellation in the heavens seemed to speak, in advance and for all time, of the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world (Jn I:29), the one who sums up in himself all the sacrifices of the innocent and gives them their meaning. The mysterious story of the ram, caught in the thicket and taking the place of Isaac as the sacrifice decreed by God himself, was now seen as the pre-history of Christ. The fork of the tree in which the ram was hanging was seen as a replica of the sign of Aries, which in turn was the celestial foreshadowing of the crucified Christ.11

After the conflict which prompted his letter, Pope St. Leo sought a more permanent solution to the disagreement with Alexandria. The result was the work of Victorius of Aquitaine. Unfortunately, even though he was tasked by Rome, Victorius did not use the Roman limits when he developed his Easter Tables and, as a result, the Alexandrian range became the standard.12 Thus the current range of the Gregorian Easter is March 22nd to April 25th, the Alexandrian range. Even so, because the date of Easter is tied to the observed Spring Equinox, which itself is associated with Aries, the date of Easter is thus always associated with Aries, even if Easter occurs when the sun has left Aries.

With regards to Easter and its association with the Spring Equinox, it would be worthwhile here to note that by the time of the Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325), due to defects in the Julian Calendar, the observed date of the Spring Equinox (March 25th) no longer corresponded with the actual astronomical event, which was then occurring around March 21st. As a result, March 21st became fixed as the Ecclesiastical/observed date for the Spring Equinox.13 The earliest Easter could be in the Alexandrian range (March 22nd) was still the day after the observed Spring Equinox (March 21st). It was imperative for the early Christians that Easter fall after the Spring Equnoix, for, as (?pseudo-)Anatolius, Bishop of Laodicea in Syria, wrote in his De ratione paschali, around the year A.D. 270:

In this correspondence of the sun and moon [i.e., the Spring Equinox], the Pasch [the Easter Sacrifice] is not to be offered up, because so long as they are discovered in this combination, power of darkness is not overcome, and as long as equality between light and darkness prevails and is not diminished by the light, it is shown that Pasch is not to be offered. And therefore it is enjoined that the Pasch be offered after the vernal equinox.14

Here Anatolius is commenting that since the Winter Solstice, the longest night and shortest amount of daylight in the year, the amount of daylight has been steadily increasing and the night has been growing shorter, while at the Spring Equinox the amount of night and daylight is equal. Anatolius reasons that since in the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ, the Light overcame darkness, its liturgical commemoration should not be celebrated until the natural light has overcome the natural darkness, which is not until at least the day after the Spring Equinox when they are equal.15

The Feast of Easter, then, is associated not only with the sun (Easter is to be celebrated after the Spring Equinox) and the moon (Easter is to fall after the full moon) as explored previously, but also with the stars by its association with Aries, the three types of heavenly bodies created by God in the Genesis account.

In a materialist society such as that in which we find ourselves today, it is very easy to see the heavenly bodies simply as combinations of atoms governed by the laws of physics, but our Christian forefathers saw in these bodies vestiges of the Divine given to provide structure to the universe. It would serve us well to regain such a worldview, one which rises above the material and sees in creation the great harmony set there by the Creator intended for all men, but especially for those redeemed by the Blood of the Son of God Who entered into the great cycles of days, months, and years, which He Himself set into motion.

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to St. Stanislaus Parish in Nashua, NH.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

-

- Strong’s Dictionary, H4150.

- Taken from an English translation from a 1967 Dominican Breviary provided by the Divinum Officium Project here.

- Bickerman, E. J. (Elias Joseph). Chronology of the Ancient World. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968), pp. 16-21.

- Ibid., p 44.

- Ibid., p. 47.

- See What is the moon phase today? Lunar phases 2024 | Space.

- Barber, Michael, Patrick. The True Meaning of Christmas-The Birth of Jesus and the Origins of the Season. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press: 2021), p. 162.

- PL 54:1055 (1844).

- PL 54:1057 (1844).

- PG 26:1355 (1857).

- Ratzinger, Joseph. The Spirit of the Liturgy. Trans. Saward, John. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), p. 99-100

- Cullen, Olive M. A Question of time or a Question of Theology: A study of the Easter controversy in the Insular Church. (Maynooth: 2007), pp. 73-74.

- The Old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Reform of the Calendar.”

- As quoted by Godard, Philip J. Festa Paschalia-A History of the Holy Week Liturgy in the Roman Rite. (Herefordshire: Gracewing, 2011), p. 20.

- The reader is no doubt familiar with the fact that the Nativity of John the Baptist (June 24th) occurs soon after the Summer Solstice (June 21st), the day with the most daylight and shortest night, and that Our Lord’s Nativity (December 25th) occurs slightly after the Winter Solstice (December 21st), the day with the least daylight and longest night. Liturgical commentators have associated the decrease of daylight associated with the Nativity of John and the increase of daylight associated with the Nativity of Christ with the following line spoke by John: “He must increase: but I must decrease” (Joh 3:30). The increase of Christ then goes on to the Spring Equinox, when daylight and night are equal, and then past to when daylight prevails, signaling the Light’s victory over darkness by Christ’s Passion, Death, and Resurrection. There does not seem to be any comparable association with the Fall Equinox, when daylight and night are equal length, although the Fall Ember Days and the associated Hebrew Festivals are celebrated around this time. In the days following the Fall Equinox, the amount of night will increase until the Winter Solstice.

September 3, 2024