Parables of Christ Part IX: Parable of the Wicked Tenants

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the August 2011 Newsletter

The parable of the wicked husbandmen is one of a select few which are found in all three synoptic Gospels. At Mass on the Friday after the second Sunday of Lent it is read from Matthew. Though it is not without its difficulties, the point of the parable—i.e. the rejection of Jewish leaders and those who followed them—was clearly understood by the chief priests and Pharisees who “knew that he spoke of them” (cf. Mt. 21:45; Mk. 12:12; Lk. 20:19).

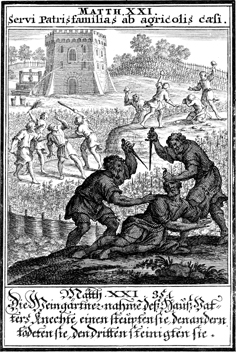

In the parable Our Lord says that a man let out his vineyard to husbandmen but when he sent his servants to request his share of the harvests, the servants were beaten and treated shamefully; some were even murdered. Lastly, the owner sent his only son who was cast out of the vineyard and killed.

In Mark and Luke, Christ tells his audience that the owner “will come and destroy those husbandmen and will give the vineyard to others.” In Matthew the audience, in response to Christ’s question about what the owner will do to punish such wickedness, replies: “He will bring those evil men to an evil end; and will let out his vineyard to other husbandmen who will render him the fruit in due season” (Mt. 21:41).

In his book, The Parables of the Gospel, Father Leopold Fonck, S.J. observes that the Jews whom Our Lord was instructing were familiar with the image of the vineyard. Isaias had written: “For the vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel” (Isaias 5:7). In speaking of the vineyard, therefore, Christ is talking about the Kingdom of God which in the Old Testament was identified with the House of Israel.

The owner of the vineyard who planted it with care is the Lord God and the messengers are the prophets whom He sent to His people. These men were treated shamefully and their message rejected. Jeremias 20:2, for example, says: “And Phassur struck Jeremias the prophet and put him in the stocks that were in the upper gate of Benjamin, in the house of the Lord.” Some were even put to death. Speaking of the prophet Urias, Jeremias writes: “And they brought Urias out of Egypt: and brought him to king Joakim, and he slew him with the sword: and he cast his dead body into the graves of the common people” (Jeremias 26:23).

When the wicked husbandmen kill the only son of the vineyard owner, their destruction is sealed. Christ, the Word made flesh, is the only Son of the Eternal Father who by means of this parable prophecies that He will be slain by the leaders of the Jews. Pontius Pilate indeed sentenced Our Lord to death but— in the words of Saint Augustine—the Jews slew Him with the sword of their tongue when they cried out to the Roman governor: “Crucify Him.” Because they rejected the Messiah, the kingdom of God is taken from them.

Christ calls Himself the cornerstone because He unites Jews and Gentiles in His Church. “And whoever falls upon this stone,” He says, “will be broken: but on whomever it shall fall, it shall grind him to powder.” In his interpretation, Father Fonk writes: “As a light potter’s vessel, if it strikes against a big stone or is hit by it, in either case is smashed to pieces, so the rejected Messiah will prove the temporal and eternal destruction of Israel.”

Father Cornelius A. Lapide, however, says that the one who falls on the stone shall bring harm to himself but in such a way that the harm may be repaired by repentance. The one on whom the stone shall fall can have no hope of reparation or restitution. Saint Thomas Aquinas, referring to Saint Jerome’s commentary, says that the one who falls on the stone is one who believes in Christ but falls on Him by committing serious sins, but the one on whom the stone falls is the one who who does not believe. A salutary application of the parable was made by Alphonsus Salmeron, S.J., one of the original companions of St. Ignatius of Loyola who became an outstanding biblical scholar. “For what the Lord predicted would happen to the Jews,” Salmeron said, “we see also to have happened in many Christian nations in Africa, Asia and in Greece.” This same application was made even more trenchantly by Bishop Cornelius Jansen, a scriptural scholar who attended the last session of the Council of Trent, “It is to be feared,” he wrote, “that the same thing happen to us, if, as many in this part of the west have already been affected, they continue to hold in contempt ecclesiastical teaching which venerable antiquity has handed down to us listen instead with itching ears to those who speak novel teachings.”

August 5, 2011