St. Peter Claver and his Interpreters

September 9th in many countries marks the feast of St. Peter Claver, who won the honors of the altar by tending to Africans being trafficked in the Atlantic Slave Trade. Claver has been specially honored across the diaspora as a great patron saint, and the study of African languages played an absolutely crucial part in his holy work.

Claver’s predecessor ministering to the Africans at Cartagena was the Jesuit Alonso de Sandoval, who had counted 70 different languages among them. Slave-masters refused to help the Jesuit find interpreters, so he was compelled to walk around the entire day looking for them. Exhausted by this, Sandoval compiled and used a little notebook, alphabetically listing interpreters’ names and addresses so that they could be easily tracked down. And even after all that, some interpreters, whether due to lack of understanding or lack of interest, didn’t faithfully convey what he told them.

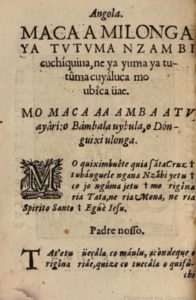

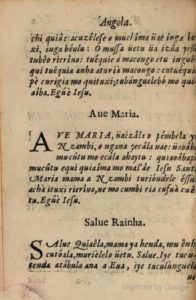

For his part, St. Peter Claver tried to remedy the situation by learning “the Angola language”, one of the primary languages spoken by the slaves at this time. This was likely the language we know today as Kimbundu, which is spoken by around 2 million souls in modern Angola, and among the first Bantu languages to be published and studied.

We do not have a great deal of information about Claver’s progress in the language, but that is perhaps the way he wanted it. For he seems to have relied not so much on his own scholarship, but on surrounding himself with a set of trustworthy African interpreters whose linguistic prowess proved absolutely indispensable to his ministry. Many of them spoke multiple languages, and one was even named after the famous Augustinian linguist Ambrosio Calepino and described as follows in 1638:

“One of them was named Calepino for knowing eleven [languages], through which God’s paternal providence evidently fights and shows how much He esteems and protects this occupation and saintly ministry, giving him to this school as a singular insignia and honor.”

Some 30 interpreters are named in the documents of the time–some of whom were consulted in Claver’s Processes of Beatification and Canonization. And from them we get a little taste of the humility of the saint.

Francisco Yolofo, a Wolof interpreter from Senegambia, related to the commission that during catechism sessions, Father Claver would have the interpreters speak from tall chairs with armrests, while he sat on a clay pot or on a piece of wood. Some European officials became angry at Fr. Claver for this arrangement, saying it was not right for the black interpreters to be seated in positions of authority over him. But the priest insisted that the interpreters were more necessary in this work than he was, and that it was vital for the catechumens to respect the catechists’ authority and believe what they said.

Toward the end of Claver’s life, his health did not permit him to go to the ships in the harbor. So he sent the interpreters by themselves–allowing them to take on his life’s work upon their own shoulders.

It is perhaps too easy for us to simply read the hagiographical accounts of thousands and thousands of Baptisms and forget that many of these were beset by seemingly insurmountable complications of language. We may think of a slave in chains bowing his head to receive the sacred waters, but we don’t generally think of the chains of interpreters required to bring him to that sacramental moment.

Certainly, as Claver himself said, it was charity and kindness that won hearts at first, not eloquence: “This was how we spoke to them, not with words but with our hands and our actions.” But we also know that the canons of the Church do not allow Baptism without prior instruction and willing acceptance–for which communication is absolutely essential. The food and water that Claver brought could only refresh bodies, not souls.

So while we honor the way St. Peter Claver and his African interpreters softened the hearts of his catechumens with physical comforts, let us remember, too, the prodigious intellectual labors involved, which opened those catechumens’ minds to a more glorious freedom than could ever be experienced on earth.

September 9, 2020