Audience with Pope Leo XIV

Official communiqué of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter – Fribourg, January 20, 2026

Following a request presented by the Superior General of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, Pope Leo XIV received Father John Berg in private audience at the Vatican on Monday, January 19, 2026. He was accompanied by Father Josef Bisig, one of the founders of the Fraternity, former Superior General, and current Rector of Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary in Denton, USA.

The cordial half-hour meeting was an opportunity to present to the Holy Father in greater detail the foundation and history of the Fraternity, as well as the various forms of apostolate that it has been offering to the faithful for almost 38 years. The proper law and charism that guide the sanctification of its members were recalled.

This audience also provided an opportunity to evoke any misunderstandings and obstacles that the Fraternity encounters in certain places and to answer questions from the Supreme Pontiff. At the end of this meeting, Pope Leo XIV gave his blessing, which he extended to all members of the Fraternity.

The Fraternity of St. Peter is grateful to the Holy Father for offering this opportunity to meet with him and encourages the faithful to continue to pray fervently during the thirty-days novena of preparation for the renewal of its consecration to the Immaculate Heart of Mary on February 11.

Source : www.fssp.org

Photos : © Vatican Media

January 20, 2026

The Other Tenth Month (Lunar)

by Fr. Mark Wojdelski, FSSP

(This is part of a series of articles, and will make little sense without the introductory articles: (1) , (2), (3), and (4). There are more than four articles in the series, but the first four are very important to understanding the conceptual framework.)

The tenth month of the lunar calendar, called Tevet, generally corresponds to the time from the end of December to the beginning of January in the Gregorian solar calendar.

It might seem strange to go through the calendar slowly like this, when nothing particularly interesting is going on. The idea is not to approach this project as liturgical scholarship strictly speaking, but rather as a kind of art appreciation. The alternative would be to fall back on a sterile historico-critical analysis of the liturgy based on the supposition that it, like everything else in our very advanced and enlightened society, can be fully and completely explained in its present form by a process of mistakes and historical processes of generation and corruption guided by some sort of “evolution.” Whether such supposed “evolution” was guided by God or not seems irrelevant to such scholarship, although scholars professing the faith would presumably not dare to suggest that the process was random, or that a certain type of popular piety at some early stage in the life of the church that became incorporated into the liturgy before detailed records were being kept was somehow a mistake. If we look at the liturgy as something that we have received, as opposed to something that is the work of particular men living at particular times in history, whose names are known, such considerations become irrelevant. Even a masterwork of art has parts that are not particularly spectacular, but are part of the whole and worthy of consideration. The liturgy makes our Lord present to us every day in much the same way that He was given to us the first time: “Yet we know where this man comes from; but when the Christ appears, no one will know where he comes from.” (Jn 7:27)

We’ve already looked at the fast observed on the tenth day of Tevet, the tenth month of the lunar calendar, and the first month of winter. (here) By way of reminder, recall that this day commemorates the beginning of the siege of Jerusalem before the destruction of the first temple. (Ezek 24:1-2) But there were a few other things that scripture records as having happened in those first two weeks of the month. I’ve previously explained why those weeks, corresponding to the first and second Sundays after Epiphany, are the only weeks that matter for our purposes.

First of all, on that same day, the 10th of Tevet, this happens to Ezekiel:

Also the word of the Lord came to me: “Son of man, behold, I am about to take the delight of your eyes away from you at a stroke; yet you shall not mourn or weep nor shall your tears run down. Sigh, but not aloud; make no mourning for the dead. Bind on your turban, and put your shoes on your feet; do not cover your lips, nor eat the bread of mourners.” So I spoke to the people in the morning, and at evening my wife died. And on the next morning I did as I was commanded.

And the people said to me, “Will you not tell us what these things mean for us, that you are acting thus?” Then I said to them, “The word of the Lord came to me: “Say to the house of Israel, Thus says the Lord God: Behold, I will profane my sanctuary, the pride of your power, the delight of your eyes, and the desire of your soul; and your sons and your daughters whom you left behind shall fall by the sword. And you shall do as I have done; you shall not cover your lips, nor eat the bread of mourners. Your turbans shall be on your heads and your shoes on your feet; you shall not mourn or weep, but you shall pine away in your iniquities and groan to one another. Thus shall Ezekiel be to you a sign; according to all that he has done you shall do. When this comes, then you will know that I am the Lord God.” (Ezek 24:15-24)

The siege of Jerusalem was announced to Ezekiel by almighty God on this day, and on that very evening, going into the following day (11 Tevet), he was to lose his wife. Moreover, he was told not to perform any outward mourning. This would have been very unusual for an observant Jew, who typically observed an entire month of mourning, beginning with with a period of seven days of intense mourning.

Perhaps we can find some connection with the end of the matins reading assigned for today, the Wednesday after the Second Sunday after Epiphany: “For godly grief produces a repentance that leads to salvation and brings no regret, but worldly grief produces death.” (2 Cor 7:10) Grief is not a bad thing, St. Paul explains, if it leads to humility and repentance. Ezekiel is not told that he should not be sad on the inside, but he is instructed not to do anything outwardly to manifest those feelings.

Although Ezekiel received word of the beginning of the siege of Jerusalem in a vision from God, he did not receive word of its destruction until three years later, but in the same month:

In the twelfth year of our exile, in the tenth month, on the fifth day of the month, a man who had escaped from Jerusalem came to me and said, “The city has fallen.” Now the hand of the Lord had been upon me the evening before the fugitive came; and he had opened my mouth by the time the man came to me in the morning; so my mouth was opened, and I was no longer mute. (Ezek 33:21–22)

The matins reading assigned for this day, the Thursday of the first week after Epiphany, is an interesting one, because it seems to be absent from the regular course of readings in the modern liturgy.

Now concerning the matters about which you wrote. It is well for a man not to touch a woman. But because of the temptation to immorality, each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband. The husband should give to his wife her conjugal rights, and likewise the wife to her husband. For the wife does not rule over her own body, but the husband does; likewise the husband does not rule over his own body, but the wife does. Do not refuse one another except perhaps by agreement for a season, that you may devote yourselves to prayer; but then come together again, lest Satan tempt you through lack of self-control. I say this by way of concession, not of command. I wish that all were as I myself am. But each has his own special gift from God, one of one kind and one of another. To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain single as I do. But if they cannot exercise self-control, they should marry. For it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion. (1 Cor 7:1–9)

Mutual rights of spouses over each other’s bodies, the preferability of continence even within marriage, and the superiority of the celibate state over the married state are rather fundamental postulates of Christianity, ideas that have sadly been under increasing attack, implicitly and explicitly, even by some inside the church. A church that attempts to overcome the unbelieving nations surrounding it by strength of numbers or any other material advantage (rather than trying to convert those people) is fighting a losing battle, putting its faith in the strength of men. (“It is better to take refuge in the LORD than to put confidence in man.” [Ps 117:8] and “Cursed is the man who trusts in man and makes flesh his arm, whose heart turns away from the LORD.” [Jer 17:5])

This might seem to have nothing to do with this day, but see what else Ezekiel says later that day, the 11th of Tevet:

Then they will know that I am the Lord, when I have made the land a desolation and a waste because of all their abominations which they have committed.

“As for you, son of man, your people who talk together about you by the walls and at the doors of the houses, say to one another, each to his brother, ‘Come, and hear what the word is that comes forth from the Lord.’ And they come to you as people come, and they sit before you as my people, and they hear what you say but they will not do it; for with their lips they show much love, but their heart is set on their gain. And behold, you are to them like one who sings love songs with a beautiful voice and plays well on an instrument, for they hear what you say, but they will not do it. When this comes—and come it will!—then they will know that a prophet has been among them.” (Ezek 33:29–33)

Three years ago, we saw Ezekiel being told not to mourn for his deceased wife, and today God speaks through him again, upbraiding the Jews for their covetousness and worldliness, and pointing ahead to the word of God spoken through St. Paul:

I mean, brethren, the appointed time has grown very short; from now on, let those who have wives live as though they had none, and those who mourn as though they were not mourning, and those who rejoice as though they were not rejoicing, and those who buy as though they had no goods, and those who deal with the world as though they had no dealings with it. For the form of this world is passing away. (1 Cor 7:29-31)

The message of Ezekiel is very similar to what our Lord said (quoting Isaiah) to those gathered to listen to Him: “This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far from me.” (Mk 7:6) Rather than allow themselves to be led by the Holy Spirit, many would rather prefer to see how hard they might push against Him without sinning.

One final event needs to be examined in this month, which took place on 8 Tevet, corresponding to the Second Sunday after Epiphany. On that day, according to an old Jewish tradition, the Septuagint translation was ordered to be prepared, supposedly at the request of King Ptolemy II of Egypt. The Septuagint (or LXX) is the translation of the Hebrew scriptures into Greek made by Jews in the diaspora. The Jews see this as a sad day; we can rather see it as something positive, as it allowed the Old Testament to be read by many very wise people who could not read Hebrew. This may have even been the means by which the wise men, well versed in the knowledge of many different religions and philosophies, knew to go to Jerusalem to consult the priests regarding the birth of the Messiah, to see if perhaps they were misreading their texts due to translation issues. The translators of the Septuagint also made a number of exegetical decisions that influenced how the scriptures would be interpreted even in the first century A.D., and Greek speakers, like St. Paul, freely used the Septuagint version directly in their writing and preaching rather than interpret the original text for their audience. It is then perhaps interesting that this day falls during the time in the cycle of the scriptural readings of the Divine Office when all the epistles of St. Paul, the apostle to the gentiles, are read at matins, starting at Christmas and ending the day before Septuagesima.

January 7, 2026

The Eyes of Our Mind

by Rev. Cav. William Rock, FSSP, SMOCSG

The Preface of the Nativity, used during the Twelve Days of Christmas, on the Feast of the Presentation (2 February, Candlemas), as well as traditionally on the Feasts of Corpus Christi (and its Octave) and of the Transfiguration (6 August),1 reads as follows:

It is truly meet and just, right and for our salvation, that we should at all times, and in all places, give thanks unto Thee, O holy Lord, Father almighty, everlasting God, for through the Mystery of the Word made flesh, the new light of Thy glory hath shone upon the eyes of our mind (mentis nostræ óculis), so that while we acknowledge God in visible form, we may through Him be drawn to the love of things invisible. And therefore with Angels and Archangels, with Throne and Dominations, and with all the hosts of the heavenly army, we sing the hymn of Thy glory, evermore saying: Holy…

Within this text is the curious phrase “eyes of the mind.” An equivalent phrase is also found the Third Oration used in the Blessing of Candles on Candlemas, the final day of the Christmas Season understood in its widest sense: “that the eye of our mind being cleansed / ut, purgáto mentis óculo.” Being aware of all this, the questions can naturally arise, what is meant by the phrase “eye(s) of the mind?” and from whence does it come? As it turns out, this phrase, “eye” or “eyes of the mind,” has a very ancient pedigree.

The ecclesiastical writer Origen (d. ~ A.D. 253) in his work Against Celsus (VII, 39), notes that the distinction between “the eye of the body and the eye of the mind,” is “borrowed from the Greeks,” that is from Greek philosophers, but he does not name which ones. An equivalent phrase, “the eye of the soul /το ομμα της ψυχης,” however, is found in the Republic (Book 7, 533.d) of Plato (d. 348/347 B.C.). The phrase “eye(s) of the mind / ocul–us, –i mentis,” or its equivalent, can be found in the works of Christian writers such as:

- St. Paul (d. A.D. ~65) used the phrase “the eyes of your heart / oculos cordis vestri / τους οφθαλμους της καρδιας υμων” in Ephesians 1:18

- St. Irenaeus of Lyon (d. A.D. ~202), Against Heresies, IV, 39, 1

- St. Hilary (d. A.D. ~367), Commentary on Matthew, Chapter 9

- St. Cyril of Jerusalem (d. A.D 368), Catechetical Lectures, Prologue, 15

- St. John Chrysostom (d. A.D. 407), Homily 7 on First Corinthians, 2

- St. Jerome (d. A.D. 420), On Isaiah, ch. 6

- St. Augustine (d. A.D. 430), passim2 (e.g. On the Trinity, XI, 3)

- St. John Cassian (d. A.D. ~435), De Inst. Coenob. viii, 6, uses the equivalent phrase “oculum cordis”

- St. Gregory the Great (d. A.D. 604), Moral. v, 45, Hom. xiv in Ezech.

- St. Isidore of Seville (d. A.D. 636), Etym. vii, 8 where he uses “intuitum mentis” and posits the soul’s imagination as another eye

- The Venerable Bede (d. A.D. 735), as quoted in the Catena Aurea, Luke, Chapter 9 where he uses “mentis aciem“

- St. Thomas Aquinas (d. A.D. 1274), e.g. Commentary on the Sentences, II, d. 22, q. 1, a. 1, ad. 1; Commentary on the Sentences, IV, d. 4 , q. 2, a. 2, r. 3

This list suffices to demonstrate the pedigree of the phrase “eye(s) of the mind,” or its equivalent, in both the East and the West. But the question still remains, what does it mean?

To answer this question, we turn to St. Augustine who made great use of this phrase. According to St. Augustine, the three highest powers of the soul are the intellect, will, and memory (see De Trin. x, 11, 17) and he identifies the “eye of the mind” with the particular power of the soul which views things (see De Trin. x, 3, 6). For Augustine, the memory presents that which is viewed by the “eye of the mind,” so the memory is distinct from the “eye of the mind.” Additionally, the will, which the Saint marks as distinct from the “eye of the mind,” does not view but rather chooses and loves. So, the “eye of the mind” cannot be the will. This leaves intellect.

So, by “eye of the mind,” one should understand the intellect, the highest power of the soul. But not just the intellect in general, nor the intellect when it undertakes discursive reasoning nor when making profound judgments, but specifically the intellect when it is contemplating, studying, identifying what is placed before its gaze. This corresponds with what St. Thomas wrote about intellectual vision (e.g. S.T. I, q. 12, a. 2, c) where the intellect is, in a sense, a “power of sight” illuminated by the natural “light” of reason and/or by supernatural “light.” Additionally, the “eyes of the mind” must be strengthened, or augmented, to be able to “see” connaturally by supernatural “light.” This augmentation is brought about by the sacrament of Baptism for, as St. Thomas wrote in his Commentary on the Sentences (cited above),

Baptism leads to external and interior spiritual vision: interior, inasmuch as Baptism is called the sacrament of faith, which makes the eye of the mind suited to seeing divine things; and external, because it is granted to the baptized and not to others to gaze upon the sacred Eucharist, as Dionysius says; and thus both Damascene and Dionysius attribute illuminative force to Baptism.

In the thought of St. Thomas, then, it is the Virtue of Faith, which is infused at Baptism and resides in the intellect (S.T. II-II, q. 4., a. 2), which augments the “eyes of the mind” to be able to “see” connaturally by supernatural “light” in this life. The supernatural “light” needed to “see” actually in a particular instance would be the “light” granted by actual grace.

Now, as the intellect is an immaterial, or spiritual, power, the “eye of the mind” is able to perceive deeper realities than the “eyes of the body,” which are limited by being material, even on the natural level. This penetration, however, is limited by the “lights” by which the “eyes of the soul” “see” and by the conditions of the “eyes of the mind” themselves. Thus, for example, while the “eyes of the body” may only see/perceive the accidents of bread when gazing on the consecrated Eucharistic Host, the “eye of the mind,” augmented by the virtue of Faith and enlightened by actual grace, “sees”/perceives/discerns the Body of Christ.

But, just as the ability of the “eye of the mind” to perceive deeper realities can be augmented/strengthened, it can also be weakened or obscured. In his work referenced above, St. Gregory wrote that “anger which comes of evil blinds the eye of the mind,” indicating that strong passions/emotions can obscure the intellect’s vision. The same can be said of sin and vice as one of the effects of sin is a blindness or a darkening of the intellect, which makes it difficult to “see” things properly (see S.T. I-II, q. 85). St. Thomas, for example, notes that by pride “the eye of the mind was impeded from actually attending to the truth of what God said [to Adam].” The removal of sin and vice allows the “eye of the mind” “to see” things more clearly in general, hence the phrase quoted earlier from the Third Oration in the Candlemas Blessing of Candles – “Blessed are the clean of heart: they shall see God” (Mat 5:8). Additionally, controlling the passions/emotions in situations when they are being greatly agitated allows for a clearer “vision” in a particular situation.

With this understanding, the Preface of the Nativity, when used during the Christmas season, can be understood in this way: The “eyes of the body” see only what is materially before them which, in the case of the newborn Christ (“God in visible form”), would only be His material Body, His Humanity. The “eyes of the mind” (the intellect), already augmented by the Faith received in Baptism, however, having received a new, supernatural “light,” that is actual grace, due to the Church’s celebration of the Lord’s Nativity, are able to perceive deeper things in “seeing” the same subject, namely “things invisible,” such as Our Lord’s Divinity.

As we continue through this year’s Christmastide, and in Christmastides of the future, may these reflections give us a deeper appreciation and a deeper understand of this curious Preface of the Nativity.

Rev. Cav. William Rock, FSSP, SMOCSG was ordained in the fall of 2019 and was invested as an Ecclesiastical Knight of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of St. George in the summer of 2025. He currently resides at the FSSP Canonical House of St. Casimir in Nashua, NH, and ministers at St. Stanislaus parish.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

- In the 1962 Missal, the Common Preface is indicated for the Feasts of Corpus Christi and of the Transfiguration. However, the 2021 CDF Ordo Divini Officii Recitandi Sacrique Peragendi allows the preface of the Nativity to be used on the Feast of Corpus Christi (p. 109) and on the Feast of the Transfiguration (p. 134) restoring the older practice. The Octave of Corpus Christi was removed from common observance under Pope Pius XII, but the same Ordo allows for exercises of piety to be continued during the days of the former Octave where there is the custom of so doing (“Peculiaria pietatis exercitia, quae cum populi concursu, diebus olim intra octavam Ss.mi Corporis Christi, ex traditione, celebrari consueverunt, continuari possunt“) (p. 109).

- In his post Upward and Inward: Augustine and Suso on Finding God Beyond and Within, Dr. Jason Baxter identified that in his Confessions, St. Augustine used the following phrases: “oculus animae /eye of the soul” (VII.10.16; VII.16.6), “acies mentis / eye of the mind” (VI.4.6; VII.1.1; VII.3.5), “interior oculus / interior eye” (XII.20.29).

January 2, 2026

Notes on Christmas and Epiphany

by Fr. Mark Wojdelski, FSSP

This is a slight departure from my series of articles on the lunar calendar in order to make some observations about the octave of Christmas. Anyone interested in the lunar calendar can start with the introductory articles: (1) , (2), (3), and (4). There are more than four articles in the series, but the first four are very important to understanding the conceptual framework.

The twelve days of Christmas have undergone a number of changes over the years. Even comparing a missal from 1862 to one from 1920, one can see significant changes, most of which took place during the reforms introduced by St. Pius X with his bull Divino Afflatu in 1911.

Before 1911, the period from December 25 to January 1 was not just a celebration of the Nativity; it was a series of overlapping octaves, where the Octave of Christmas coexisted with the octaves of the so-called Comites Christi (“Companions of Christ”): St. Stephen, St. John, and the Holy Innocents. These have been described elsewhere (here), but one should realize that by Dec. 29, the feast of St. Thomas of Canterbury, a priest celebrating Mass would have been commemorating four different octaves.

A close study of the rubrics of the octave of Christmas in the pre-Divino Afflatu missal shows some interesting things, most of which have been observed previously (e.g. here). First of all, the three saints immediately after Christmas, even if they fall on a Sunday, were always celebrated on their proper days. The observance of the Sunday within the octave in these cases was moved to the 30th of December, immediately after the feast of St. Thomas of Canterbury. However, if Sunday fell on the 29th of December, the day of the feast of St. Thomas, a much later addition to the octave (13th cent.), the Sunday was celebrated on that day, and St. Thomas was forced to move to the 30th. This represented a departure from the normal rankings of feasts, as St. Thomas was celebrated as duplex feast, while the Sunday was semiduplex, as almost all Sundays were.

Another strange thing happened if Christmas fell on a Monday. In this case, and this is the only case in which this can occur after St. Thomas of Canterbury was added to the octave, the “Missa de Octava” is celebrated on Saturday, Dec. 30. This Mass is still used on all the days of the Christmas octave that do not have a saint’s feast assigned to them. It is essentially the third Mass of Christmas day, with the epistle and gospel from the Mass of dawn. In the 1960 rubrics, this Mass can theoretically be celebrated on Dec. 29-31, since the saints’ feasts on those days were reduced to commemorations.

In the pre-Divino Afflatu rubrics, there was only one case in which this Mass could ever be celebrated during the octave of Christmas: if the day after St. Thomas (Dec. 29) should fall on a Saturday. Then on Sunday, Dec. 31, St. Sylvester (a feast going back to the fourth century) was celebrated, and the Sunday was only commemorated. This is very curious, since in other such cases, when an important Sunday was impeded, it was quite natural to anticipate its Mass and office on the previous Saturday. This is what used to happen if, for example, a Sunday after Epiphany (always the second) were “swallowed up” by Septuagesima because of a very early Easter. There is clearly something unusual about the Sunday within the octave of Christmas, the Mass “Dum medium silentium,” which was also used for the Vigil of Epiphany (also suppressed in the rubrical reforms of 1960).

This might seem to be irrelevant information, but the apparent liturgical chaos that takes place between Christmas and Epiphany seems to overlap with some of the 11 days which my lunar calendar schema cannot deal with. I will just say now that I have no idea what to do with it, except to note two things: first, that the first Sunday after it (wherever “it” might be) corresponds to the first day of Tevet, the first winter month. The second thing to note is that Epiphany in the West was not uniformly observed. In the Eastern traditions it was celebrated as the birthday of Christ, before the feast on Dec. 25 began to be observed, but this was a feast which migrated from the West. In the Milanese tradition, it even seems to have been a movable feast (to some extent) celebrated before Christmas.1 But it is generally agreed upon that the feast of the Nativity of Christ on Dec. 25 was the original observance in Rome, Epiphany not arriving until later, so the fact that it seems to have no place in the reconstructed lunar calendar is not particularly upsetting, since all of these lunar vestiges (revolving around Easter, remember) would have crystallized fairly early, certainly well before St. Thomas was added to the octave, and likely even before St. Sylvester, and probably before there was an octave (or even a feast?) of Christmas.

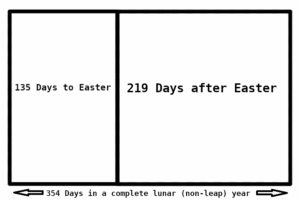

In order to help all of this make sense, here is a “complete” lunar calendar, radiating out from Easter Sunday as previously discussed.

January 1, 2026

The FSSP 30-Day Novena to Our Lady begins January 12th

For the Members of the Confraternity of St. Peter

A thirty-day novena in preparation for the renewal of the Fraternity’s consecration to the Immaculate Heart of Mary is being organized this year.

It will begin on Sunday, January 12, 2026, and end on February 11, 2026, the anniversary of the consecration, when the act of consecration will be publicly renewed.

The preparatory thirty-day novena will consist of the daily recitation of a decade of the Rosary and the Memorare.

To conclude this thirty-day novena, the General House, the seminaries, the North American Province, and the Districts will send representatives this year to Fatima, on February 10 and 11, 2026. There, they will renew the consecration of the entire Fraternity to Our Lady at the site of the apparitions.

December 30, 2025

Upcoming FSSP Retreats in the Philadelphia Area

St. Mary’s apostolate in Conshohocken, PA has announced two FSSP-led silent retreats in the Philadelphia area. Note that the Registration cutoff for the Men’s Retreat is Jan 15th, and the cutoff for the Women’s Retreat is Feb 6th.

Traditional Men’s Silent Retreat

February 6-8th, 2026

The Holy Name Society of St. Mary, Conshohocken, PA is organizing a Traditional Men’s Silent Retreat at Malvern Retreat House in Malvern, PA from February 6-8, 2026.

Retreat Master: Fr. Lee, FSSP Professor at FSSP Seminary in Nebraska

Open to family and friends that are practicing Catholics – men 18 and older. Cost is $345 – includes accommodations & meals. Contact Ken Orner at stmarys.hns.treasurer@gmail.com for additional information.

Traditional Women’s Silent Retreat

March 20-22 , 2026

The Confraternity of Christian Mothers of St. Mary, Conshohocken, PA is organizing a Traditional Women’s Silent Retreat at Malvern Retreat House in Malvern, PA from March 20-22, 2026. Retreat Master: Fr. Gregory Eichman, FSSP. Head of the Year of Spirituality at the FSSP Seminary in Nebraska.

Open to family and friends that are practicing Catholics – women 18 and older. Cost is $345 – includes accommodations & meals. Contact Robyn Stratton at stmarywomansretreat@gmail.com for questions.

Please register at this link: https://forms.gle/jRjUR1WKPwepJPtf6

December 22, 2025

The Fast of the Tenth Month

by Rev. Cav. William Rock, FSSP, SMOCSG

Before there was Advent, there were the precursors of Advent, the Greater Ferias, the Church’s response to Saturnalia, and the days of the Fast of the Tenth Month, better known today as the Ember Days of December.1 With respect to their origin, the Ember Days seem to be a christianization of Roman agricultural celebrations with the December Ember Days being the christianization of the feriæ sementivæ,2 the festival after sowing,3 “for the seeding.” Lest there be any confusion regarding calling the December Ember Days the days of the Fast of the Tenth, and not the Twelfth, Month, it is important to note that the Roman calendar, prior to the reform under Julius Caesar (d. 44 B.C.), originally marked the beginning of the year in the spring with March being the first month,4 thus making December the tenth, hence the name (decem, “ten”).5 And while December was not the tenth calendar month at the dawn of Christianity, it was still the tenth month by name.

For those who may be unfamiliar, the Ember Days are four sets of three days (Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday) somewhat evenly spaced throughout the year which are kept as days of penance. In the 1917 Code of Canon Law, the Ember Days were to be kept as days of fasting and abstinence, with no exception for those which corresponded with the Octave of Pentecost (the Ember Days, it should be noted, predate this Octave) (canon 1252.2). By 1962, the abstinence on Ember Wednesdays and Saturdays was reduced to partial. These sets of days, as they correspond, some better than others, with the changes of natural seasons, were observed as a way to give thanks to God for the blessings of the previous season and to ask His blessing on the one beginning. As ordinations at Rome historically occurred on Ember Saturdays, these days were also days of preparation for this event.

Some authors, such as Servant of God Dom Prosper Guéranger,6 attempt to justify the keeping of the Ember Day fasts by invoking the Prophet Zacharias (8:19): “Thus saith the Lord of hosts: The fast of the fourth month, and the fast of the fifth, and the fast of the seventh, and the fast of the tenth shall be to the house of Juda, joy, and gladness, and great solemnities: only love ye truth and peace.” The Fast of the Tenth Month mentioned by the Prophet, then, would correspond with the December Ember Days. The Fast of the Seventh Month, for its part, would correspond with the September Ember Days, September being the original seventh Roman month (septem, seven).7 The Fast of the Fourth Month would correspond with the Ember Days following the Feast of Pentecost which can fall between May (the third month) 10 and June (the fourth month) 13. If one were to assign a correspondence in the Roman liturgical calendar for the Fast of the Fifth Month, the fasts before the Feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist and before the Feast of Sts. Peter and Paul, both celebrated in late June, close to July, the original fifth Roman month, serve as possible candidates. It is not by coincidence, then, such authors would argue, that this passage of the Prophet is read as part of the Fourth Lesson on September’s Ember Saturday (Zach 8:14-19). Rather, it is the Church’s liturgy itself giving witness to the origin of these fasts.

It is clear, however, that there is not a perfect correspondence between the passage from Zacharias and the Roman liturgical calendar. This is most likely due to the Prophet being invoked as a justification for a practice which was already being kept rather than the passage serving as the inspiration of the practice. As was said above, the origin of the Ember Days is more likely a christianization of Roman agricultural celebrations at a very early date rather than the application of the writings of an Old Testament Prophet to the Christian liturgical year, although the Scripture text may have inspired the names of these christianized observances. Repeating what was said above, the Winter Ember Days seem to correspond with the December sowing festival, while the Summer Ember Days correspond with the feriæ messis (“for a bountiful harvest”), and the Autumn Ember Days with the feriæ vindimiales (“for a rich vintage”), with the Lenten, or Spring, Ember Days, which seem to be without an agricultural precedent, being added to balance out the year.8 Dom Guéranger himself notes that “in the early writers” there is mention “of the three times [of fasting] and not the four,”9 but argues this is because the Ember Days of Lent add nothing to the Lenten fast already being observed. Again, it seems more likely that the Spring Ember Days were added later, but by the time of Pope Gelasius (A.D. 492-496), to balance out the calendar.

In Matins, the Church’s night office, for the First, Third and Fourth Sundays of Advent, prior to the changes made to the Breviary under Pope John XXIII (d. A.D. 1963),10 the readings for the second nocturns are taken from the sermons of Pope St. Leo the Great (d. A.D. 461) on the Fast of the Tenth Month.11 For the sake of the edification of the faithful as we enter into these Winter Ember Days and so that they may keep these days with the same spirit which was expected of the early Christians and which the Church perennially expected of her children by including them in her liturgy, I here present translations of these readings.

For the First Sunday of Advent from Leo’s Eighth Sermon on the Fast of the Tenth Month and Almsgiving:

Our Saviour Himself instructed His disciples concerning the times and seasons of the coming of the Kingdom of God and the end of the world, and He hath given the same teaching to the Church by the mouth of His Apostles. In connection with this subject then, Our Lord biddeth us beware lest we let our hearts grow heavy through excess of meat and drink, and worldly thoughts. Dearly beloved brethren, we know how that this warning applieth particularly to us. We know that that day is coming, and though for a season we know not the very hour, yet this we know, that it is near.

Let every man then make himself ready against the coming of the Lord, so that He may not find him making his belly his god, or the world his chief care. Dearly beloved brethren, it is a matter of every day experience that fulness of drink dulleth the keenness of the mind, and that excess of eating unnerveth the strength of the will. The very stomach protesteth that gluttony doth harm to the bodily health, unless temperance get the better of desire, and the thought of the indigestion afterward check the indulgence of the moment.

The body without the soul hath no desires; its sensibility cometh from the same source as its movements. And it is the duty of a man with a reasonable soul to deny something to his lower nature and to keep back the outer man from things unseemly. Then will his soul, free from fleshly cravings, sit often at leisure in the palace of the mind, dwelling on the wisdom of God. There, when the roar and rattle of earthly cares are stilled, will she feed on holy thoughts and entertain herself with the expectation of the everlasting joy.12

For the Third Sunday of Advent from Leo’s Second Sermon on the Fast of the Tenth Month and Almsgiving:

Dearly beloved brethren, with the care which becometh us as the shepherd of your souls, we urge upon you the rigid observance of this Fast of the Tenth Month [décimi mensis celebrándum esse jejúnium]. The month of December hath come round again, and with it this devout custom of the Church. The fruits of the year, which is drawing to a close, are now all gathered in, and we most meetly offer our abstinence to God as a sacrifice of thanksgiving. And what can be more useful than fasting, that exercise by which we draw nigh to God, make a stand against the devil, and overcome the softer enticements of sin?

Fasting hath ever been the bread of strength. From abstinence proceed pure thoughts, reasonable desires, and healthy counsels. By voluntary mortifications the flesh dieth to lust, and the soul is renewed in might. But since fasting is not the only mean whereby we get health for our souls, let us add to our fasting works of mercy. Let us spend in good deeds what we take from indulgence. Let our fast become the banquet of the poor.

Let us defend the widow and serve the orphan; let us comfort the afflicted and reconcile the estranged; let us take in the wanderer and succour the oppressed; let us clothe the naked and cherish the sick. And may every one of us that shall offer to the God of all goodness of the sacrifice of this piety of fasting and alms be by Him fitted to receive an eternal reward in His heavenly kingdom! We fast on Wednesday and Friday; and there is likewise a Vigil on Saturday at the Church of St. Peter, that by his good prayers we may the more effectually obtain what we ask for, through our Lord Jesus Christ, Who with the Father and the Holy Ghost, liveth and reigneth, God, world without end. Amen.

For the Forth Sunday of Advent from Leo’s First Sermon on the Fast of the Tenth Month and Almsgiving:

Dearly beloved brethren, if we study attentively the history of the creation of our race, we shall find that man was made in the image of God, that his ways also might be an imitation of the ways of his Maker. This is the natural, real, and highest dignity to which we are capable of attaining, that the goodness of the Divine nature should have a reflection in us, as in a glass. As a mean of reaching this dignity, we are daily offered the grace of our Saviour, for as in the first Adam all men are fallen, so in the Second Adam can all men be raised up again i Cor. xv. 22.

Our restoration from the consequences of Adam’s fall is sheer mercy of God, and nothing else; we should not have loved Him unless He had first loved us 1 John iv. 19, and scattered the darkness of our ignorance by the light of His truth. This the Lord promised by the mouth of Isaiah, where He saith: Isa. xlii. 16, I will bring the blind by a way that they knew not, and I will lead them in paths that they have not known I will make darkness light before them, and crooked things straight. These things will I do unto them and not forsake them. And again: Isa. lxv. 1, 2; Rom. x. 20, I was found of them that sought Me not; I was made manifest unto them that asked not after Me.

And we know from the Apostle John how God fulfilled His promise, 1 John v. 20. We know that the Son of God is come, and hath given us an understanding, that we may know Him That is True, and be in Him That is True, even in His Son. And again: iv. 19, Let us therefore love God, because He first loved us. For His great love then wherewith he hath loved us, Eph. ii. 4, God reneweth His likeness in us. And, moreover, in order that He may find in us the reflection of His goodness, He giveth us that whereby to work along with Himself, (Who worketh all in all,) lighting, as it were, candles in our dark minds, and kindling in us the fire of His love, to make us love not Himself only, but likewise, in Him, whatsoever He loveth.

Rev. Cav. William Rock, FSSP, SMOCSG was ordained in the fall of 2019 and was invested as an Ecclesiastical Knight of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of St. George in the summer of 2025. He currently resides at the FSSP Canonical House of St. Casimir in Nashua, NH, and ministers at St. Stanislaus parish.

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

- Talley, T. J. The Origins of the Liturgical Year. (New York: Pueblo Books, 1986), pp. 149-151.

- The old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Ember Days.”

- Whitaker’s Words, s.v. “Sementivus.”

- Whitaker’s Words, s.v. “Decem.”

- The old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “New Year’s Day.”

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, vol. 1 (Advent). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto

Publications, 2000), pp. 218-221. - Whitaker’s Words, s.v. “Septem.”

- The old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Ember Days.”

- Guéranger, p. 219.

- In the changes made by Pope John XXIII in 1960, Sunday Matins was reduced to one nocturn and the readings of the second nocturns omitted. With respect to the matter at hand, it seems to be a great loss that the Winter Ember Day sermons of Leo, which testify to their antiquity, are no longer part of the Church’s official liturgy.

- The corresponding readings for the Second Sunday of Advent are from St. Jerome’s commentary on Isaias 11, touching particularly on the Root of Jesse, from which the readings of the first nocturn are drawn.

- The translations of Leo’s sermons are taken from the Divinum Officium Project with modifications in some places.

December 14, 2025

The Ninth Month, concluded

by Fr. Mark Wojdelski, FSSP

(This is part of a series of articles, and will make little sense without the introductory articles: (1) , (2), (3), and (4). There are more than four articles in the series, but the first four are very important to understanding the conceptual framework.)

Continuing our look at the month of Kislev, loosely corresponding with December, the last fall month in the Roman calendar:

“And the Lord opened the womb of Leah, and she conceived and bare Jacob a son, and he called his name Reuben, on the fourteenth day of the ninth month, in the first year of the third week.” (Jubilees 28:11)

The book of Jubilees is a pre-Christian work, dated between 160-150 B.C., and is regarded as apocryphal by Christians and Jews alike. Nevertheless, it sometimes adds some details that might be significant, especially given its antiquity. Such ancient texts often reflect some old traditions that might be worthy of consideration. It is important to remember that the spirit of prophecy still existed among the people of God (perhaps in a more subdued form) even in the later post-exilic centuries before the coming of Christ.

Returning to the canonical scriptures, the birth of Reuben is very appropriate for this time of year:

And Leah conceived and bore a son, and she called his name Reuben; for she said, “Because the Lord has looked upon my affliction; surely now my husband will love me.” (Gen 29:32)1

God the Father was certainly greatly pleased by the birth of His Son from the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and He loved her all the more because of it. The 14th day of the month is typically the day on which the full moon rises at sunset, heading into the 15th day.2

Things take a turn for the worse for the Jewish people, however, for on the very next day in their history the following event is commemorated (skipping ahead quite a bit historically speaking). We now find ourselves in the time of the Maccabees:

Now on the fifteenth day of Chislev, in the one hundred and forty-fifth year, they erected a desolating sacrilege upon the altar of burnt offering. They also built altars in the surrounding cities of Judah, and burned incense at the doors of the houses and in the streets. The books of the law which they found they tore to pieces and burned with fire. Where the book of the covenant was found in the possession of any one, or if any one adhered to the law, the decree of the king condemned him to death. They kept using violence against Israel, against those found month after month in the cities. (1 Mac 1:54-58)

This “desolating sacrilege” is perhaps better known as an “abomination of desolation.” This continues through to the end of the month:

They kept using violence against Israel, against those found month after month in the cities. And on the twenty-fifth day of the month they offered sacrifice on the altar which was upon the altar of burnt offering. According to the decree, they put to death the women who had their children circumcised, and their families and those who circumcised them; and they hung the infants from their mothers’ necks. (1 Mac 1:59-60)

All these events harmonize well with the matins reading assigned to the Saturday of the second week of Advent, from Isaiah, the prophet of consolation (15 Kislev on our constructed calendar):

O Lord, you are my God; I will exalt you, I will praise your name; for you have done wonderful things, plans formed of old, faithful and sure.

For you have made the city a heap, the fortified city a ruin; the palace of strangers is a city no more, it will never be rebuilt.

Therefore strong peoples will glorify you; cities of ruthless nations will fear you.

For you have been a stronghold to the poor, a stronghold to the needy in his distress, a shelter from the storm and a shade from the heat; for the blast of the ruthless is like a storm against a wall, like heat in a dry place.

You subdue the noise of the strangers; as heat by the shade of a cloud, so the song of the ruthless is stilled.

On this mountain the Lord of hosts will make for all peoples a feast of fat things, a feast of choice wines—of fat things full of marrow, of choice wines well refined. And he will destroy on this mountain the covering that is cast over all peoples, the veil that is spread over all nations. He will swallow up death for ever, and the Lord God will wipe away tears from all faces, and the reproach of his people he will take away from all the earth, for the Lord has spoken.

It will be said on that day, “Behold, this is our God; we have waited for him, that he might save us. This is the Lord; we have waited for him; let us be glad and rejoice in his salvation.” (Is 25:1-9)

The Ember days of Advent have been often connected with the “fast of the tenth month.” (Zech 8:19) As we have previously seen, this is not entirely accurate but understandable in the context of the possible development of the Roman liturgy from primitive Jewish practices, because Roman sensibilities were also taken into account, according to whom, the “first month” was not April, but March. Absolutely no reference is made in the Roman liturgy at this point in the year to the fast of the tenth month commemorating the beginning of the siege of Jerusalem. Instead, the Ember Days of Advent all deal with some aspect of the Incarnation, that is, the rebuilding of the temple that was destroyed. The gospel of Ember Friday is particularly significant, as it reminds us that it is the voice of Our Blessed Mother that “undoes” the curse of Eve3 when she salutes Elizabeth, and it is at the sound of her call that the infant John leaps in the womb of St. Elizabeth.

We continue on through the month, and leaving aside the hardships that the Jews are going through in the time of the Maccabees, we are reminded of still other hardships that they underwent after their time of exile in Babylon. Unfortunately we are jumping all around history now, from the time of the Maccabees all the way back to the time of the building of the second temple:

On the twenty-fourth day of the ninth month, in the second year of Darius, the word of the Lord came by Haggai the prophet, Thus says the Lord of hosts: Ask the priests to decide this question, ‘If one carries holy flesh in the skirt of his garment, and touches with his skirt bread, or pottage, or wine, or oil, or any kind of food, does it become holy?’ ” The priests answered, “No.” Then said Haggai, “If one who is unclean by contact with a dead body touches any of these, does it become unclean?” The priests answered, “It does become unclean.” Then Haggai said, “So is it with this people, and with this nation before me, says the Lord; and so with every work of their hands; and what they offer there is unclean. Please now, consider what will come to pass from this day onward. Before a stone was placed upon a stone in the temple of the Lord, how did you fare? When one came to a heap of twenty measures, there were but ten; when one came to the winevat to draw fifty measures, there were but twenty. I struck you and all the products of your toil with blight and mildew and hail; yet you did not return to me, says the Lord. Consider from this day onward, from the twenty-fourth day of the ninth month. Since the day that the foundation of the Lord’s temple was laid, consider: Is the seed yet in the barn? Do the vine, the fig tree, the pomegranate, and the olive tree still yield nothing? From this day on I will bless you.” (Hag 2:11-19)

It seems the point being made here is that the container does not sanctify what touches it, implying that the Blessed Virgin was sanctified before becoming the mother of God. Mere physical proximity or contact is not enough to remove a stain of sin, even if it can cure one of physical ailments, as it did several times during the earthly ministry of Christ and even the apostles. But once the body is sanctified by grace, that grace cannot be lost except by an act of the will, since we have been taught that nothing that goes into the body can defile it, only what comes out of it. (Mt 15:11) In the case of the Mother of God, neither what went into her nor what came out of her ever defiled her. How many mothers can say the same about what came from their wombs, the very same which was nourished and raised by them? Only one mother in all human history can honestly say that she did not contribute to the problem of every act of procreation propagating the sin of Adam, because she did not participate in this act natural generation which serves to propagate the sin of Adam.

The word of the Lord came a second time to Haggai on the twenty-fourth day of the month, “Speak to Zerubbabel, governor of Judah, saying, I am about to shake the heavens and the earth, and to overthrow the throne of kingdoms; I am about to destroy the strength of the kingdoms of the nations, and overthrow the chariots and their riders; and the horses and their riders shall go down, every one by the sword of his fellow. On that day, says the Lord of hosts, I will take you, O Zerubbabel my servant, the son of Shealtiel, says the Lord, and make you like a signet ring; for I have chosen you, says the Lord of hosts.” (Hag 2:20-23)

Zerubbabel is a direct ancestor of our Lord. (Mt 1:12) The foundations of the second temple were laid in Jerusalem on this day. Some later traditions connect this to the rededication of the second temple under the Maccabees (see below). Presumably the temple was recaptured on this day, the 24th, and the rededication took place on the following day.

Jumping forward again to the time of the Maccabees, after their city and temple were defiled, we are told:

But many in Israel stood firm and were resolved in their hearts not to eat unclean food. They chose to die rather than to be defiled by food or to profane the holy covenant; and they did die. And very great wrath came upon Israel. (1 Mac 1:63-64)

After the heroic Jews regain control of the temple three years later, we read:

Early in the morning on the twenty-fifth day of the ninth month, which is the month of Chislev, in the one hundred and forty-eighth year, they rose and offered sacrifice, as the law directs, on the new altar of burnt offering which they had built. At the very season and on the very day that the Gentiles had profaned it, it was dedicated with songs and harps and lutes and cymbals. All the people fell on their faces and worshiped and blessed Heaven, who had prospered them. So they celebrated the dedication of the altar for eight days, and offered burnt offerings with gladness; they offered a sacrifice of deliverance and praise. They decorated the front of the temple with golden crowns and small shields; they restored the gates and the chambers for the priests, and furnished them with doors. There was very great gladness among the people, and the reproach of the Gentiles was removed.

Then Judas and his brothers and all the assembly of Israel determined that every year at that season the days of the dedication of the altar should be observed with gladness and joy for eight days, beginning with the twenty-fifth day of the month of Chislev. (1 Mac 4:52-59, cf. 2 Mac 10:5)

This, of course, is the origin of the Jewish observance of the eight days of Hanukkah, nowadays observed some time in late November through mid-December. Just as we have seen some other solar dates line up with lunar observances, this one comes as no surprise, and is celebrated around the same time of year. December is in fact considered a fall month, not a winter month, snowy decorations aside, and so once again we see signs that some days numbered on the lunar calendar show up on the same-numbered analogous day on the solar calendar (the third fall month in both cases). This particular day seems to be the one nobody argues about because everyone wants to feel warm and fuzzy around the holidays. Hanukkah rarely beginning on or after Dec. 25 might explain the secular Christmas season creeping back into Advent. It is ironic, but very consoling, that we consider as inspired scripture the very writings (the books of the Maccabees) that establish this observance, while the Jews themselves (as well as most protestants) consider them apocryphal. This is most unfortunate, as the stories of the heroic Maccabees have been inspiring to Catholics for centuries, especially the story of the seven brothers and their mother who were martyred. (2 Mac 7) We just read about these events about two months ago. Perhaps we are meant to turn these things over in our minds once again around this time of year, as the the Nativity of our Lord draws near, since, as we well know, the disciple is not greater than the Master.

1 “Reuben. The name, literally “Look, a son!” is given a composite symbolic explanation (from two sources): rāʾā be– “he saw, looked at,” and (yeʾehā) banī “he will love me.” The plain connotation is of course the real one; cf. the Akkadian name Awīlumma “it’s a man/male,” and cf. Job 3:3.” [quoted from E. A. Speiser, Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, vol. 1, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 230].

2 Most definitely in a “short month” of 29 days, which this is in our arrangement

3 i.e. And to Adam he said, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife, and have eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, ‘You shall not eat of it,’ cursed is the ground because of you.” (Gen 3:17)

4 “At Milan the Christmas feast comes after the feast of Epiphany, the latter being celebrated earlier at Milan than at Rome. To calculate the feast of Epiphany at Milan, the Eastern computation, which was based on the phase of the moon, was used. Thus the celebration of the feast of Easter at Milan did not coincide with the celebration at Rome.” (Gabriel Ramis, “The Liturgical Year in the Non-Roman West,” in Liturgical Time and Space, ed. Anscar J. Chupungco, vol. 5 [The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, MN, 2000], 212)

December 12, 2025

Liturgical Guides to the Seasons

New to the Latin Mass, or do you just need a quick guide to the seasons as we start a new liturgical year?

New to the Latin Mass, or do you just need a quick guide to the seasons as we start a new liturgical year?

Our own Fr. William Rock has authored a number of Extraordinary Guides. These 2-page guides are information-packed glimpses at each liturgical season, showcasing the origin of the season’s name, its major themes, its dates and duration, and its special liturgical and devotional characteristics, such as changes to the Mass, colors, and special blessings and feasts.

Print them out and share them with friends and family, and make your liturgical year more extraordinary!

December 1, 2025

The Ninth Month

by Fr. Mark Wojdelski, FSSP

(This is part of a series of articles, and will make little sense without the introductory articles: (1) , (2), (3), and (4). There are more than four articles in the series, but the first four are very important to understanding the conceptual framework.)

Now we will look at Kislev, the ninth month of the Hebrew religious calendar, i.e. the third month of the civil calendar, to see what else might be hiding in plain sight. Something odd will happen between this month and the next month, which we will see when it happens in its proper place, and any suggestions as to what is going on at that point will be more than welcome. Nevertheless, we arrive at the beginning of this month not counting forwards from Easter, but in the backwards direction, and according to that method of reckoning, the first day of the month falls on Saturday, the Sabbath. This is interesting because it just so happens that no matter what, according to the modern Molad1 used by the Jewish people, the beginning of Kislev can never fall on the Sabbath, just as according to their same manner of arranging the calendar, Nisan always has 30 days, whereas in our idealized schema, as has been shown, it must have had 29, at least in those years when it mattered.

The idea of counting days backward before Easter has already been discussed (here) but exactly how far forward and back one should go is not immediately obvious. It might seem that going back only as Septuagesima or the first Sunday after Epiphany or some other arbitrary point might be preferable and our reconstructed lunar year could end with Kislev, rather than the alternative. However, the striking thing about this precise arrangement is that the days before and after Easter are arranged in the so-called golden ratio. 220/134 is within .02 of the “golden ratio” (~1.618).2 Recall that the ordinary lunar calendar of 354 days divides neatly into two halves, each comprised of 177 days. We’ve already seen that pivot points around Easter and Sukkot, and Good Friday and the Ember Friday in September exist, but Christianity takes the lunar year and causes it to undergo an asymmetric fission, as it were, with the point of cleavage being the Feast of Feasts, the Resurrection.3

Regardless of the arrangement of the matins readings of previous weeks, which were arranged according to the solar month, we can be very certain of the readings of the final week after the 24 Sundays of Pentecost. The reading assigned for the day immediately before the beginning of Advent is from the prophet Malachi, the last of the prophetic books of the Old Testament:

The oracle of the word of the Lord to Israel by Malachi.

“I have loved you,” says the Lord. But you say, “How have you loved us?” “Is not Esau Jacob’s brother?” says the Lord. “Yet I have loved Jacob but I have hated Esau; I have laid waste his hill country and left his heritage to jackals of the desert.” If Edom says, “We are shattered but we will rebuild the ruins,” the Lord of hosts says, “They may build, but I will tear down, till they are called the wicked country, the people with whom the Lord is angry for ever.” . . . I have no pleasure in you, says the Lord of hosts, and I will not accept an offering from your hand. For from the rising of the sun to its setting my name is great among the nations, and in every place incense is offered to my name, and a pure offering; for my name is great among the nations, says the Lord of hosts. (Mal 1:1-4,10-11)

The end of this book is also very appropriate:

Behold, I send my messenger to prepare the way before me, and the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple; the messenger of the covenant in whom you delight, behold, he is coming, says the Lord of hosts. ( Mal 3:1)

For behold, the day comes, burning like an oven, when all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble; the day that comes shall burn them up, says the Lord of hosts, so that it will leave them neither root nor branch. But for you who fear my name the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings. You shall go forth leaping like calves from the stall. And you shall tread down the wicked, for they will be ashes under the soles of your feet, on the day when I act, says the Lord of hosts.

“Remember the law of my servant Moses, the statutes and ordinances that I commanded him at Horeb for all Israel.

“Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and awesome day of the Lord comes. And he will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, lest I come and strike the land with a curse.” (Mal 4:1-6)

These would be the most relevant passages, but the whole book is worth reading; it is not that long. The fact that in our hypothetical calendar this day falls on the Sabbath, the seventh day of the week, is certainly noteworthy. The last day of the week dawns into the first day of the week, the first day of the season of Advent, the beginning of the liturgical year, which might also remind us of the new beginning on Easter Sunday: “Now after the sabbath, toward the dawn of the first day of the week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to see the tomb.” (Mt 28:1)

And then, a few days after that, 8 Kislev, Saturday, the day of the week that eventually became devoted to the Blessed Virgin Mary, at matins we have the following:

And the Lord spoke again to Achaz, saying: Ask thee a sign of the Lord thy God, either unto the depth of hell, or unto the height above. And Achaz said: I will not ask, and I will not tempt the Lord.

And he said: Hear ye therefore, O house of David: Is it a small thing for you to be grievous to men, that you are grievous to my God also? Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign. Behold a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son and his name shall be called Emmanuel. He shall eat butter and honey, that he may know to refuse the evil, and to choose the good. (Is 7:10-15)

It’s probably nothing, but such coincidences do seem to happen from time to time. Keep in mind that if there is anything to these distant connections, they are but faint echoes. The main action takes place during the weeks leading up to and following the Exodus. It is hoped that these reflections might continue to help the reader integrate the liturgy and scripture into his life in a new, more profitable way.

1 The tables that are used to calculate when the new moons should fall according to an idealized calculation (see earlier articles for an explanation)

2 The “exact” center is about 5 hours after sunset on Easter Sunday, while the Israelites might have been crossing the Red Sea.

3 The idea of looking for the golden ratio was suggested (after I had intuitively decided how to make the division) by a close childhood friend of mine, Prof. Mark Nowakowski, a music professor at Kent State, who has been working on a book on aesthetics.

November 26, 2025