Tolkien’s Creation of Species

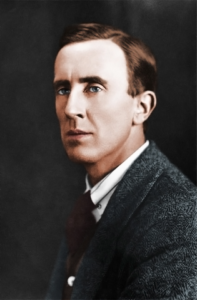

As Amazon has released and wrapped up their first season of “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power”, regardless of how the show has performed, it is safe to say that the imaginative world of J.R.R. Tolkien is back on the menu. For many, it is an opportunity to delve back in to a world of fantasy that formed many of our imaginations in our youth; for others, perhaps it is a first taste and an invitation to truly explore this world in its source material for the first time. While the world created by Tolkien is a fantasy, it is a fantasy that comes from the mind and imagination of a Catholic man, and in this way there are many aspects that are imbued with a elements of Catholic faith and symbolism. To this end we offer the following reflection on some of the Catholic symbolism and imagery contained in the world of Tolkien, originally presented by our French district in their publication “Claves”.

Originally published at Claves.org. Translated by Anastasiia Cherygova.

Who are the creatures inhabiting the world of “The Rings of Power”?

The series produced by Amazon opens with a very quick indication of the creation of the world of rings, elves, dwarves and many others – in Tolkien’s writings, these species tell us much about ourselves by means of a symbolic device of a fairy tale, which is possible to decode through the author’s own correspondence.

Introduction: Biblical Allegory or Christian Fairy Tale?

The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings are fairy-tale-like works whose inspiration is inherently Christian. Tolkien formally stated that: “The Lord of the Rings is, of course, a fundamentally religious and Catholic work”.1 However, one must understand in what way it is such: Tolkien never intended to create an allegory of revealed mysteries, like, for instance, was done in the Chronicles of Narnia of his friend C.S. Lewis.2

The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings are fairy-tale-like works whose inspiration is inherently Christian. Tolkien formally stated that: “The Lord of the Rings is, of course, a fundamentally religious and Catholic work”.1 However, one must understand in what way it is such: Tolkien never intended to create an allegory of revealed mysteries, like, for instance, was done in the Chronicles of Narnia of his friend C.S. Lewis.2

According to Tolkien, in allegories, the author would use a sort of “code language” which one would then decipher.3 Once the audience discovers how, all the symbols become transparent; for instance, that of Aslan being Christ, the White Witch being the devil, etc.

Tolkien did not write that way: he does not seek to impose on his audience a single framework for decoding. He is also not the master of his work to the point of telling what aspect of the “secondary world” corresponds verbatim, word for word, to another aspect of the “primary world”. Instead, he presents which figures of his fairy tale can be compared to a certain reality because the aforementioned figures are more or less consciously inspired from these realities.4 Thereby we get what we could call a diffused Christian symbolism, spread throughout Tolkien’s entire written corpus, so that every reader may, if desired, put oneself to the task and recognize it. On the surface, The Lord of the Rings does not advertise itself as a Christian work. Yet in its essence and central inspiration it is such a work. From time to time, perhaps even often, in one or another character or situation, a Christian idea would present itself, becoming almost evident, but the reader must be willing to see it.

1. A Christian-Inspired Mythology: Eru, Valar and Maia

Tolkien’s fantasy work begins in The Silmarillion with what could be called a creation myth of his world. Yet from the first lines it is obvious that this creation myth is born of a Christian inspiration. First and foremost because there is only one god. Tolkien’s secondary world is not explicitly Christian – there is no question about the Trinity – but it is basically monotheistic. Everything that exists proceeds from the only god named Eru (the Only One) or Illuvatar (the Illuminator). The first creation, in turn, consists of pure spirits called Ainur (meaning Blessed or Saints) or Valar (meaning Powers or Authorities). Whom do Ainur/Valar resemble in the primary world? With whom are they “associated”? Tolkien responds to this in numerous letters: with angels.5 These are created spirits among whom exists a hierarchy. Some rest with the Only One to sing the eternal music of creation. They are like the seraphim (“angels in waiting”) in the terminology of Dionysius Areopagite. Others are closer to the visible world, Earth, Arda in The Silmarillion, which would become “Middle Earth” after a great cataclysm, reminding us of the Biblical flood and especially the Atlantis myth. These are like the archangels (“sent angels”), working on a mission in the visible world for the sake of its inhabitants. Valar are themselves Ainur, the angelic spirits of the first order that the Only One sent on Earth, and these Valar in turn sent the spirits of a lesser order, Maia. Gandalf is one of the Maia, the most loyal and the most active, sent by Valar in the third age of the world to help humans in their battle against Sauron, who is himself a fallen Maia.

Thus, there is an entire invisible host of creation in Tolkien’s secondary world, a hierarchy of spirits created by the Only One that clearly harkens back to the angelic orders of the Christian revelation. Gandalf was compared by Tolkien to a guardian angel, akin to the guardian angel of Middle Earth.6 And through a character like Gandalf, Tolkien reminds us that the lot of humans in visible creation does not depend only on the visible causes. Instead, humans depend, first and foremost, on the actions of invisible, but completely, real forces. Forces that could sometimes become visible, and that are always helping us or harming us. Man thus belongs to two worlds: to the invisible world through his soul and to the visible world through his body. His battle is therefore primarily a spiritual one, bearing a challenge that surpasses the visible world.

2. Man and His Images: Elves, Dwarves and Hobbits

One of Tolkien’s ideas consists in the fact that, before the “fourth age”, the age of human dominion, many species would appear on Earth and prepare it for the reign of man. These are Elves, the firstborns of the Only One in Arda, as well as Dwarves and Hobbits, or halflings. Why go with these imaginary species, at times similar to man, yet also different from him? Tolkien himself answers quite clearly: elves, dwarves and hobbits are in and of themselves images of man and his nature, with his very complex and very different capacities and aspirations.

Elves

Elves, as writes Tolkien, “represent the artistic, aesthetic and purely scientific aspects of human nature elevated to a higher degree than what we find among humans”. This is why elves are passionate about art, poetry, music, but also sciences. They very much like to work with matter to improve and beautify it. In addition to this, elves possess certain privileges that allow them to attain in their work great perfection. Privileges that are inaccessible for fallen man, specifically immortality. Tolkien specifies that this immortality is limited, measured by the life of the physical world itself. Elves last as long as the Earth itself lasts, until the end appointed by Eru. What will come of them afterwards is not indicated.

Does this suggest that elves are akin to humans raised to perfection in every way, freed from all human foibles? The answer is no: elves could be killed. Even more significantly, they are morally fallible, like all creatures. They could become prideful, egotistical, excessively possessive, as represented in the storyline of The Silmarillion. Elves could become entangled in attachment to their craft to the point of rejecting one of the most essential characteristics of the world: its finitude, its corruptibility, its proneness to change and, ultimately, to destruction. This is the tragedy of the elves: they are immortal, but the created world, which they love deeply, isn’t. If they revolt against this condition, they subsequently become the “embalmers”, those who in vain attempt to rid the present world from its eventual change and from its finitude, constraining it in a “perfect” state, at least in the elves’ eyes.7 They thereby fall victim to the temptation of a kind of transhumanism.

Thus, elves constitute for us, just as Tolkien’s other imaginary species, at one and the same time an example and a warning. If you could surpass yourself by science or by art, if you could create a truly beautiful masterpiece, or if you could discover through your research new scientific realities, you will overcome death as long as it is allotted to you, being “sagely elf-like”. But if you would flee into the aesthetic dreams, if you would become egoistical and possessive about your knowledge or your art, if you would enclose yourself in the nostalgia for a bygone past, then you would become “foolishly elf-like”, degrading yourself by what is supposed to elevate you.

Dwarves

When it comes to the dwarves, they represent an “earthly” side of human nature; the desire to work the land, to extract its various riches, to construct sturdy homes that would defy time. That’s why dwarves are small – close to the ground – robust, capable stone masons, blacksmiths and exceptional goldsmiths, living in mountains and caves. They are brave and tough, but they could also be terribly stubborn, spiteful and prone to unbridled greed, the traits that are exemplified by dragons. This was the situation of Thorin in The Hobbit. The dwarves of Tolkien tell us: “Work the land, shape gold and silver, but do not become voracious like the dragons because you are made for something greater than this.”

Hobbits

Finally, hobbits are an ordinary humble people of simple tastes, with a penchant for good food and cozy homes. They are “average men”, whence comes their small size. They are often too limited, too down-to-earth homebodies, but they are also capable of rising to heroism, if they are helped by their greaters. It is the meeting with Gandalf and the elves that would reveal the dormant heroism of Bilbo and subsequently that of Frodo and Sam.

Conclusion

Through his imaginary species, Tolkien managed to present a lively and convincing image of the possibilities of human nature, of all its strengths and its desires, which could ennoble man or at the same time degrade him. The perfect man would be the one who is able to embody simultaneously the contemplative spirit of the elves, the readiness to work and the patience of dwarves, and the good sense of realism of hobbits. In creating a fellowship of two humans, four hobbits, an elf and a dwarf together around Gandalf, “the guardian angel” of Middle Earth, in their battle against Sauron, it is as if Tolkien tells us: do not neglect anything that you have within yourself, cultivate your best gifts and let the grace of God purify them and elevate them. This is how you will contribute, for your part, to pushing back against evil and increasing the good in the world.

References

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Letters, Letter No. 142 to Fr. Robert Murray, (S.J.), p. 332.

- Tolkien would reiterate this affirmation more than once in his correspondence. For example, in letter 181 to Michael Straight, dated approximately January or February 1956 (estimated), op.cit., pp. 447-448: “There is absolutely no (underlined within text) moral, political or contemporary “allegory” in this work. It is a “fairy tale”, but written – according to the conviction that I previously expressed in a long essay “About the Fairy Tale”, that it is an appropriate audience – for adults. For I think that fairy tale has its own way of reflecting about the “truth”, different from the one expressed in allegory, in satire or in “realism” – and in a certain way a more powerful one.”

- Tolkien underscores several times in his letters that he himself discovered certain characters and certain events of his story in the process of writing. He was personally quite surprised by it. Cf., for instance, letter 163 to W.H. Auden, pp. 416-417.

- We find a good example of this viewpoint in the already cited letter to R. Murray. Father Murray had written to Tolkien that the elf-queen Galadriel made him think of the Virgin Mary. Tolkien answers him by saying: “I think I see exactly what you mean (…) by your references to Our Lady, on whom is built all of my own perception, a limited one, of beauty, in majesty and in simplicity alike” (Letter 142, p. 331). Tolkien did not at all conceive Galadriel as an allegory of the Blessed Virgin. But the Blessed Virgin represents for him an ideal of feminine beauty. In imagining a very beautiful elf-queen, that is to say a human woman, but endowed with a fairy-like beauty which surpasses all the possibilities of this world, he could not have not been inspired, even unconsciously, by the idea that he got from the Blessed Virgin Mary. He thus gave to Galadriel the traits that are “associated” to the Blessed Virgin.

- For example, letter 153 to Peter Hastings, op. cit., p. 373: “The immediate authorities are the Valar (the Powers or the Authorities): the “gods”). But they are only created spirits – of an elevated angelic order, we should say, assisted by lesser angels – worthy of reverence, thus, but not of adoration.”

- Cf. Letter 156 to Robert Murray, November 4, 1954, p. 389: “I would venture to say that he (Gandalf) was an ‘angel’ incarnate, strictly speaking about an ἀγγελος: that is to say, with other Istari, mages, ‘those who know’ (Istari is translated as “wizard” because of a link with the words “wise” or “witting”, mind and knowledge, specified by Tolkien, p. 399), an emissary of the Gods of the West, send to the Middle Earth while a formidable crisis provoked by Sauron was looming on the horizon.” Tolkien well specifies in this letter in what sense Gandalf is really “dead” following the battle with the Balrog, and the fact that his return, with a new body, endowed with greater powers, is not thanks to the Valar, but to the Creator.

- Cf. Letter 181, p. 455 : “Like if a man should hate a very long, unending book, fixating himself on the chapter that he likes the most.” Some elves have “fallen into the trap of Sauron” that the art rings taught them because they had an excessive desire for power, in hopes of “stopping the change, keeping everything new and beautiful, forever.”

November 23, 2022