Use, Representation, and Being – The Rational Elevation of Material Creation in Man’s Worship

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

Man is called to worship the True God “in spirit and in truth” (Joh 4:23). This, however, should not be construed to limit man’s worship to simply an internal activity taking place in one’s intellect and will, his spiritual powers. As man is a creature composed of body and soul, it is natural and fitting that man’s internal sentiments be expressed externally during his acts of worship, which externals also then serve to stir up further the internal sentiments. These external manifestations of one’s internal sentiments most naturally include actions and position of the body. Furthermore, to make this external worship even more fitting, man makes use of other material creatures. By so doing, these other material creatures are elevated from their natural condition and become participants in man’s rational worship of their common Creator. However, there are other ways in which man brings the rest of material creation with him into worship.

It is clearly expressed in the Holy Scriptures that God has given man dominion over the rest of material creation (e.g., Gen 1:26, 28). A dominion which, while weakened, was not lost with the Fall (e.g., Gen 9:2; Ps. 8:5-9 [Vulgate numbering]). Those that have dominion are, due to that very fact, empowered to represent those who are under their care. The head of the house can represent the entire household. The king can represent all those in his kingdom. Man, then, can represent all of material creation before God when worship is being officially conducted.

Additionally, man is able to represent all of creation before God because in man all of the various aspects of creation are unified. At the conclusion to the Gospel of Mark, Our Lord commands the Apostles to “preach the Gospel to every creature” (Mar 16:15). In his 29th Sermon on the Gospel, St. Gregory the Great explains this passage as follows:

When then, He had rebuked the hardness of their [the Apostles’] heart, what command did He give them? Let us hear. “Go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel to every creature.” Was the Holy Gospel, then my brethren, to be preached to things insensate, or to brute beasts, that the Lord said to His disciples: “Preach the Gospel to every creature”? Nay, but by the words “every creature” we must understand man, in whom are combined the qualities of all creatures. Being [existence/esse] he hath in common with stones, life in common with trees, feeling in common with beasts, understanding in common with angels. If, then, man hath something in common with every creature, man is to a certain extent every creature. The Gospel, then, if it be preached to man only, is preached to every creature.1

If the Gospel, in being preached only to man, is preached to every creature, then when man worships, every creature worships, in a certain way, also.

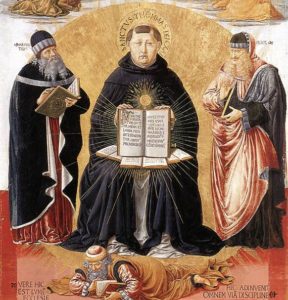

The final mode in which man incorporates the rest of creation in his worship is a bit intricate. I ask your indulgence, dear reader, as we progress. According to Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy (the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas building on that of Aristotle), the substantial form of the thing makes a thing to be the type of thing it is. A tree, then, is a tree because it possesses the substantial form of tree, a dog is a dog because it possesses the substantial form of dog, and so on. It is also the conviction of Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy that in his process of knowing, man replicates in his mind, through an involved process, the substantial form of what he knows. So, in knowing trees and dogs, the substantial forms of trees and dogs are obtained by the knowing human mind. But if the possession of substantial form makes something to be this or that type of thing, and if man possesses the substantial forms of other things in his mind (importantly, in a way different from that by which the other things possess their proper substantial forms), then man, while still remaining a human being, in a way, becomes also all those other things which he knows. It is the position of Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy that man becomes, in a certain way, what it is he knows.2 This is expressed by Aristotle when he wrote in his De Anima that “in the soul is there something by which it becomes all things.”3 Fr. Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange, O.P., arguably the greatest Thomist of the twentieth century, following the long and prestigious line of those following St. Thomas Aquinas, encapsulates this position as: “the knower becomes the other inasmuch as it is other.”4

As man becomes, in a certain way and while still remaining substantially human, what he knows, then when man comes to worship, he not only elevates material creation by its use and represents all of creation before God, man worships God as what he knows. Man not only represents, for example, trees during his worship, he actually worships, if he knows them, as tree. In short, man worships as those other aspects of creation which he knows by a change in his own being through his act of knowing.

An application of this final mode of representing creation before God can be found in praying the hymn Benedicite, which the three youths sang in the fiery furnace in Babylon (Dan 3:57-88, 56). Throughout the course of this hymn, the one at prayer invites many aspects of creation to join him in blessing the Lord. But by doing so, he himself becomes, in a certain way, that portion of creation he is addressing and worships God on their behalf.5

With the greater appreciation which the knowledge of this article brings to the Faithful of the role they have in worship with respect to the rest of creation, it would be proper, as each is preparing for Mass, to form an intention to represent all of creation before God.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Translation based on that from The Divinum Officium Project; Ninth Reading of the Feast of the Ascension.

- See S.T. I, q. 14, a. 2; S.T. I, q. 87, a. 1, ad 3; Summa Contra Gentiles, II, 74; Commentary on the De Anima III, lect. 7, n. 787-790; McInerny, D. Q. Epistemology. (Elmhurst: The Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, 2007), especially pp. 72-73 (The Epistemological Marriage).

- Aristotle, De Anima, III, 4, 430a10-17 as quoted by St. Thomas (S.T. I, q. 79, a. 3, s.c.).

- Garrigou-Lagrange, Réginald. Philosophizing in Faith: Essays on the Beginning and End of Wisdom. Trans. Minerd, Matthew K. (Providence: Cluny Media Publications, 2019), 63. See also Garrigou-Lagrange’s articles The Threefold Foundation of Thomistic Realism (Le réalisme thomiste: Son triple fondement) and On the Nature of Knowledge as Union with the Other as Other (Cognoscens quodammodo fit vel est aliud a se), available in translation in this work.

- Dr. Peter Kwasniewski, PhD, in his New Liturgical Movement article “Preach the Gospel to Every Creature”: The Benedicite, also addresses the subject of this article.

August 22, 2022