Benjaminite Comites

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

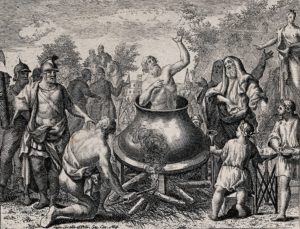

The three Feasts following Christmas – St. Stephen, St. John the Apostle, and the Holy Innocents – are known as the Comites Christi, that is, the “Companions of Christ,” as they are the first Saints on the liturgical calendar to attend, as it were, to the newborn Christ Child. These three feasts are also seen as representing the three forms of martyrdom. St. Stephen, the Protomartyr, was a martyr in desire and in act, St. John was a martyr in desire but not in act (he was miraculously saved when cast into boiling oil, which miracle resulted in his exile to the Island of Patmos),1 and the Holy Innocents were martyrs in act but not in desire. The liturgical colors traditionally assigned to each day reinforced this distinction – St. Stephen’s feast with red, St. John’s with white, and the Holy Innocents’ with violet.2 The importance of these feasts was also manifested in that each, in addition to Christmas, was celebrated with an octave. But there is another discernible theme running through these feasts and that is the Hebrew tribe of Benjamin.

Depending on where the stoning of St. Stephen, the first martyr after the Resurrection, occurred, he may have been martyred in the territory of the tribe of Benjamin as the city of Jerusalem is divided between the territories of the tribes the Judah and Benjamin (Act 7:58). More clearly, the conversion of the Apostle Paul, of the tribe of Benjamin (Phil 3:5), is attributed, at least in part, to the prayers offered up by Stephen for those persecuting him (Act 7:59). For Paul was present and held the cloaks of those conducting the execution, thus consenting to it.

St. John can also be seen as having a connection to the tribe of Benjamin. But in order to understand this, it is important to recognize, as Dr. Brant Pitre explains in his Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary – Unveiling the Mother of the Messiah, that the person of Joseph, son of Jacob/Israel and Rachel, is a type or foreshadowing of Our Lord and Rachel of Our Lady. As Dr. Pitre spends an entire chapter explaining these connections, a full analysis cannot be presented here, but it is important to note that Joseph and Benjamin were brothers, the sons of Jacob/Israel and Rachel and that Rachel was the most-favored and most-beloved wife of Jacob. This is why Joseph was favored by Jacob above the rest of his brothers. He was the firstborn of Rachel, the most-beloved wife. Joseph, for his part, showed special love and affection for his only full-brother, Benjamin, the younger son of Rachel.

The Benjaminite connection with St. John the Apostle comes from his crucifixion account where Our Lord, the new Joseph, gives St. John to Our Lady, the new Rachel, as a second son. The second son of Rachel, as was stated, was Benjamin. Following the pattern, this would make St. John a new Benjamin. Dr. Pitre argues the St. John was aware of this as he never names himself in his Gospel, rather he calls himself the “disciple whom Jesus loved.” For in the Book of Deuteronomy (33:12), it is written that Benjamin is “beloved of the Lord.” Dr. Pitre’s position can be summarized as follows:

In order words, just as Benjamin was specially loved by Joseph because they were both sons of Rachel, so John is especially “loved” by Jesus because they have the same mother. Just as Joseph was the firstborn son of Rachel in the Old Testament, so Jesus is the firstborn son of Mary in the New Testament. And just as Benjamin was the “son” of Rachel’s “sorrow” [Rachel originally named her second son “Benoni, that is, the son of my sorrow: but his father called him Benjamin, that is, the son of my right hand” (Gen 35:18)], because she had to die to give birth to him, so John becomes the “son” of Mary’s sorrow, because Mary becomes his mother only through the anguish and “sorrow” that she experiences at the foot of the cross.3

Finally, there are the Holy Innocents. The connection between the Holy Innocents and Benjamin is made explicitly by Scripture itself, for in their regard St. Matthew in his Gospel draws from this prophecy of Jeremias: “then was fulfilled that which was spoken by Jeremias the prophet, saying: A voice in Rama was heard, lamentation and great mourning; Rachel bewailing her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not” (Mat 2:17-18). This prophecy is applicable because Rachel “was buried in the highway that leadeth to Ephrata, this is Bethlehem” (35:19) and it was not just the babies in Bethlehem who were martyred, but also those “in all the borders thereof” (Mat 2:16), and Bethlehem, although in the territory of the tribe of Judah, is close by the territory of the tribe of Benjamin, whose mother was Rachel. As such, the horror ordered by Herod would have spilled over from the territory of the tribe of Judah into that of Benjamin also. The Roman Church recognizes the connection of the Holy Innocents with tribe of Benjamin by appointing the Church of St. Paul Outside the Walls as the Station Church for this feast. As stated above, St. Paul was of the tribe of Benjamin.

The question can now be asked, what is the purpose of the theme of Benjamin present in these feasts? In the first place, Benjamin, by association, brings to mind Joseph and Rachel. As such, these feasts shed light on the two major feasts between which the Comites fall. On Christmas Day, the beloved Son of the Father was born from the most-beloved Spouse of the Holy Ghost, the Blessed Virgin Mary, the new Rachel. This Son will be condemned by those to whom He desires to be close, as Joseph was, but, in the end, God, as He did with Joseph, will use the inflicted evil to save those who share in the guilt of the condemnation. Turning to the Octave Day of Christmas, it must be noted that the prophecy of Jeremias quoted in connection with the Holy Innocents was made centuries after Rachel’s death and gives witness to the belief that Rachel, although dead, was still aware of what was occurring in the land of the living and would intercede on behalf of the living. In fact, it was held that her intercession was greater than that of Moses and Abraham.4 As the new Rachel, it would be expected that Mary would also act as a maternal intercessor in heaven for those still on the earth. And this is what is found in the Collect and Postcommunion in the Mass for the Octave Day of Christmas. In these prayers, the Church invokes Mary’s intercession.

Secondly, it must be remembered that Benjamin means “son of my right hand.” In Sacred Scripture, the “right hand” is often a sign of strength or power (e.g., Ps 117:16). So, Benjamin could be understood to mean “son of my power.” Martyrdom, for its part, requires a special grace from God to undergo not only death in witnesses of the Faith, but also to endure without apostatizing the horrible tortures and pains which, in many cases, accompany the deathblow.5 In honoring the martyrs, then, Christians not only celebrated the witness provided by individual martyrs but also the victory won by Christ through them. As a special grace, a special strength, from God is needed to undergo martyrdom for the faith, each martyr can be seen as a “son of God’s power,” every martyr can be seen as a Benjamin of God. This may explain why the theme of Benjamin is present in these three feasts which represent the three types of martyrdoms.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Prior to the liturgical reforms of 1960, the Feast of St. John before the Latin Gate, which commemorated this attempted martyrdom, was observed on the universal Roman liturgical calendar as a major double on May 6th. While the feast is no longer observed, the Mass of this feast may be said on this day.

- For more information about these feasts see Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, 2 (Christmas). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000).

- Pitre, Brant. Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary – Unveiling the Mother of the Messiah. (New York: Image Press, 2018), 177.

- Pitre, 168.

- For example, see Garrigou-Lagrange, Réginald. The Priest in Union with Christ. Part 3, Section 2, Chapter 3

December 26, 2022