Do You Hear What I Hear?

By Fr. William Rock, FSSP

The Liturgical Year, with all of its seasons and feasts of the temporal cycle, is a whole. While this is hard to see as the faithful progress from one season to another, from one feast to another, it is nevertheless true and can be seen when examined with this view in mind. Holy Mother Church, for her part, leaves little hints here and there to lift the minds of the faithful to such considerations. One of the ways she does is by her use of chant and this from nearly the beginning of the Liturgical Year.

During the Office of Prime, the Martyrology1 entry for the following day is sung, when the Office is fully chanted, in the Prophecy Tone. This tone is also used for all the pre-Epistle Lessons sung at Mass, such as on Ember Days, during the ceremonies of the Triduum, and other such occasions. But during Prime of the Vigil of Christmas, Christmas Eve Day, something unique happens. After the usual introduction (which indicates the day of the Moon), the reading of the Martyrology commences with the Christmas Proclamation which details the lapse of time from various historical events to the Nativity of the Lord. There is a fittingness that these historical events leading up to the coming of the Lord should be sung in a Tone called Prophecy as at those times there was only a promise of a Redeemer yet to come.

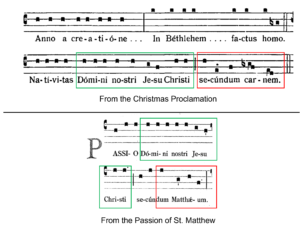

But then, when the chanter reaches the phrase “in Bethlehem of Juda, is born of the Virgin, Mary, being made Man,” he raises the pitch of the chant a fourth,2 marking, perhaps, with excitement, the end of the time of promise, of expectation, and the start of something new, while all kneel, reverencing the Mystery of the Incarnation as during the Angelus, the Credo, and the Last Gospel of St. John’s Prologue. Then, exceptionally, the last line of the Proclamation – “The Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ according to the Flesh!” – is sung in tone which is similar to that used by the narrator during the Passions in Holy Week. In this way, the Liturgy links the celebration of the Nativity of Our Lord and His Passion and Death as presented during the liturgies of Holy Week and brings to mind that Christ came into this world to suffer and to die for our salvation.

As an aside, but still in keeping with the broader subject matter of this article, this is not the only instance during Advent which points forward to the Passion of Christ. During Vespers on the Sundays and Ferias of Advent, the Church sings in her hymn Creator alme siderum the following:

Who, that thou mightst our ransom pay

And wash the stains of sin away,

Wouldst from a Virgin’s womb proceed

And on the cross a victim bleed.3

Thus, from the First Vespers of the First Sunday of Advent, the Church is looking forward to the Passion. A similar tone is taken in the Advent Lauds Hymn, En clara vox redarguit:

Lo, the Lamb, so long expected,

Comes with pardon down from heaven;

Let us haste, with tears of sorrow,

One and all to be forgiven.4

The Lamb, referring to Christ, is an animal of sacrifice.

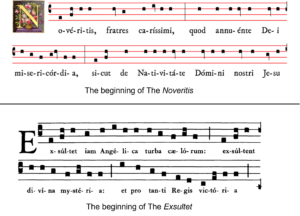

As the Liturgical Year transitions from Advent to Christmas, and then from Christmastide to the Feast of the Epiphany, another instance emerges. After the chanting of the Gospel on the feast of the Epiphany, the Noveritis (named from the first word of the text) is traditionally chanted at principal churches. This proclamation makes known to the faithful that year’s dates of Easter, Septuagesima, Ash Wednesday, Ascension, Pentecost, Corpus Christi, and the First Sunday of Advent (which are all moveable). As Dom Guéranger wrote in his Liturgical Year, “this custom…shows both the mysterious connection which unites the great Solemnities of the year one with another,” echoing the current general theme, “and the importance the faithful ought to attach to the celebration of the greatest one of all,”5 Easter. As the faithful are honoring the manifestations of Christ on the Epiphany, they will also celebrate Him, on the announced date of Easter, as the Conqueror of Death. But it is not just in the announcing of the Feast of Easter that this connection is made, for the chant of the Noveritis is nearly the same as the Exsultet of the Easter Vigil. As such, this chant gives a taste of Paschal joy and expectation to this publication of the date of Easter.

If these aforementioned chants can be used to point future events in the Liturgical Year, then their later use must necessarily point backwards. For would not hearing the Narrator of the Passions during Passion Week bring the faithful back in mind to the start of the Liturgical Year when it first resounded through the sacred edifice? And would not the strains of the Exsultet harken the listeners back to the proclamation which followed so quickly on the Lord’s Nativity? And just as Easter Sunday could not exist without Good Friday, so neither could the Exsultet be sung if it were not proceeded by the Passions. Nor could there be a Passion if there were no Incarnation and no public manifestations (epiphanies) of the Incarnate One.

If these aforementioned chants can be used to point future events in the Liturgical Year, then their later use must necessarily point backwards. For would not hearing the Narrator of the Passions during Passion Week bring the faithful back in mind to the start of the Liturgical Year when it first resounded through the sacred edifice? And would not the strains of the Exsultet harken the listeners back to the proclamation which followed so quickly on the Lord’s Nativity? And just as Easter Sunday could not exist without Good Friday, so neither could the Exsultet be sung if it were not proceeded by the Passions. Nor could there be a Passion if there were no Incarnation and no public manifestations (epiphanies) of the Incarnate One.

This wholeness of Our Lord’s life, then, is not neglected by His Spouse, Holy Mother Church, for when she makes present to the faithful, through the sacred signs of the liturgy, what must necessarily be expressed in distinct observances by her children, time-bound, material creatures, she expresses that such observances are parts of a greater whole, connecting them in ways which reveal both her maternal solicitude for her children and her liturgical ingenuity.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

1. A book which contains many of the Saints and liturgical events associated with each given day.

2. Johner, Dominic. A New School of Gregorian Chant. New York: Fr. Pustet & Co., 1925, p 325. The notation for the Christmas Proclamation shown in the image is taken from here also, while the notation for the Passion, slightly modified, is taken from Cantus Passionis Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Matthaeum, Marcum, Lucam et Joannem. Ex Editione Vaticana, 1953, p. 7.

3. Britt, Matthew. The Hymns of The Breviary and Missal. New York: Benziger Brothers, 1936, pp. 95-97. This hymn is from the 7th century and is from the Ambrosian school. A more literal translation of the above is: “To expiate the common guilt of mankind, Thou, a spotless Victim, didst go forth to the Cross from the sacred womb of a Virgin.”

4. Ibid., pp 99-100. This hymn is from the 5th century and is from Ambrosian school. A more literal translation of the above is: “Behold, the Lamb is sent to us, to pay our debt gratuitously: together, let us all with tears pray for pardon.”

5. Prosper, Guéranger. The Liturgical Year – Volume III – Christmas, Book II. Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000, p. 124. The translation of the Christmas Proclamation is taken from the same work, volume I, p. 511. The notation for the Noveritis shown in the image, as well as the image from the Pontificale is taken from Schola Sainte Cécile’s and the notation for the Exsultet is taken from the Roman Missal.

December 15, 2021