The New Founders of Rome, Part 2: The Monuments

by Claudio Salvucci

Out of the thousands of modern tourists who flock to Rome yearly, it’s doubtful that any are there primarily to pay their respects to monuments of King Romulus or the god Quirinus.

There was actually a quite famous site associated with Romulus in antiquity: the Casa Romuli or “Hut of Romulus” at the southwest corner of the Palatine, which apparently consisted of a mud-and-straw peasant’s house that had been repeatedly damaged and rebuilt over the centuries. St. Jerome lived in sight of it during his time in Rome, but he thought very little of it and was more at home with the holy places of Bethlehem.

The Romulan legacy still endures in archaeology and myth, but his story is not the one whose monuments draw the crowds.

That distinction belongs to St. Peter and the Roman martyrs.

Tourism to Rome’s Christian sites can be traced back to the second century. Gaius, a local priest who flourished around the year 200, tells us the following, in a quote that was preserved by Eusebius:

“But I can show the trophies of the apostles. For if you will go to the Vatican or to the Ostian way, you will find the trophies of those who laid the foundations of this church.”

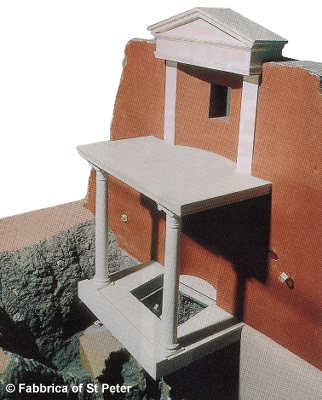

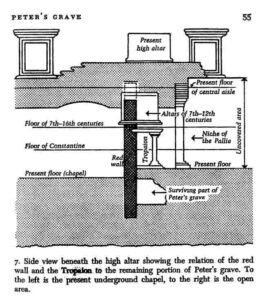

“Trophies” here is not like a modern athletic trophy but is a translation of the Greek word tropaion, a victory monument. And in fact, the monument Gaius spoke of, lost to the eyes of men for centuries, was rediscovered during the archaeological excavations under St. Peter’s Basilica in the 1940s.

The Liber Pontificalis, an ancient chronicle of the Popes, contains additional information. It states that the second and third Popes, St. Linus and St. Cletus, were both “buried near the body of blessed Peter in the Batican”. Furthermore, it states that the third Pope, Anencletus:

built and adorned the sepuchral monument of the blessed Peter, forasmuch as he had been made priest by the blessed Peter, and other places of sepulchre for the burial of bishops. There he himself was buried near the body of the blessed Peter, July 13.

We are not certain of the reliability of this information, mainly because the extant sources differ on whether Popes Cletus and Anencletus are two separate people or the same person. Moreover, the excavations have not turned up evidence for a sepulchral monument built during the years given for Anencletus: A.D. 84-95.

What archaeology has confirmed, however, is that 1st-century and 2nd-century graves surrounded Peter’s own grave, as if the deceased had wanted to be buried as close to the original grave as possible. Then, around the years 150-165, as determined by dateable bricks found at the site, Gaius’s tropaion was built at the site. As it happens, the Pope reigning from 157-168 was named Anicetus–so some scholars are convinced the Liber Pontificalis got the facts right but transcribed the name of the Pope wrong.

In any case, historical documents and archaeology both point to the fact that Peter’s grave was remembered and honored continually, starting from his earliest successors in the first century, and continuing into the middle of the second century when Christians first built a small monument over the grave.

Of course we also know that the modest monument that was first built over the tomb of the Apostle was not the last.

Of course we also know that the modest monument that was first built over the tomb of the Apostle was not the last.

But note: the sanctity of the site was such that even as subsequent Emperors and Pontiffs added to the majesty of the memorial, they shied away from destroying the work of their predecessors, instead tending to simply add to what was there already. Grave beside grave, tropaion above grave, memorial around tropaion, altar atop memorial, and finally altar atop altar.

The great Constantinian basilica that was built to honor Peter’s grave was precisely engineered over the existing tropaion–a project that required massive construction work, including leveling the natural hill and some of the necropolis that had grown up around the site. Constantine’s basilica, regrettably, is no more, but it stood for over a thousand years, and only when it was crumbling and beyond repair was an even larger and more magnificent basilica built around it.

This “new” basilica is the St. Peter’s that we know today.

And during that building process five centuries ago, the Popes created a new body called the Reverenda Fabrica Sancti Petri, the Factory of St. Peter, to manage the construction, maintenance, and decoration of the building as well as the tomb of the Apostle.

This organization is still plugging away at that task today, with no end in sight. So much so that the modern Romans have an expression “com’a fabrica de San Pietro”–“like the Factory of St. Peter”–for an interminable task that is perennially under construction and never actually finished.

As such the Basilica Sancti Petri may well serve as a metaphor for the whole church militant here on earth–still carefully guarding the Apostolic legacy it received during its earliest days, and still being built slowly and laboriously by human hands.

But still–what humanity can do with its own hands is limited. Even monuments solidly built and carefully tended still degrade and decay. Moreover, a stone monument can only remind us of ones who once walked on the earth–it is an inferior and inanimate remembrance of a living human soul.

A far better tribute would be to elevate a living person into a higher level of being. Something greater than he was. Something supernatural.

This even the pagans knew, which is why the Romans deified their first founder.

Yet they hardly expected to share his fate. Deification was a singular privilege of Romulus’s status as a demi-god and his foundation of Rome. His wife Hersilia was allowed to share his singular privilege; but that was as far as it went. As Augustine pointed out (see Part I for the quote), not even Romulus’s brother and co-founder Remus was deified.

Ordinary, mortal Romans were at best destined for the Limbo-like pleasantries of Elysium rather than experiencing any kind of transformation by the divine nature that the gods enjoyed.

Their second founder, however, taught to them a new and quite different doctrine, received directly from the lips of a Divinity:

Simon Peter, servant and apostle of Jesus Christ, to them that have obtained equal faith with us in the justice of our God and Saviour Jesus Christ. Grace to you and peace be accomplished in the knowledge of God and of Christ Jesus our Lord: As all things of his divine power which appertain to life and godliness, are given us, through the knowledge of him who hath called us by his own proper glory and virtue. By whom he hath given us most great and precious promises: that by these you may be made partakers of the divine nature: flying the corruption of that concupiscence which is in the world.

Through Christ it is not just Rome’s founder, but the Roman people themselves–all the Roman people–who are invited to partake in the divine nature. Not just Peter, but Agnes, Cecilia, Frances, and all the saints whom we honor at our altars in addition to myriads we have never even heard of.

In the eyes of eternity, and of the faithful who visit the city, these are all a part of Rome’s truest and greatest tropaion, and a more permanent memorial than a few marble columns and slabs beneath the Vatican.

July 14, 2023