The New Founders of Rome, Part 1: the Feast

by Claudio Salvucci

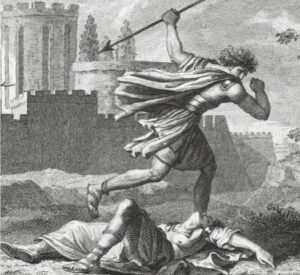

According to legend, the city of Rome was founded on April 21st, 753 B.C. by a pair of twins named Romulus and Remus. When Remus made sport of Romulus’s still rudimentary defenses and leapt over them, he was killed for the slight, and so it was Romulus who gave his name to the city, became its first king, and established so many of its civic institutions, including its calendar and its religion.

According to legend, the city of Rome was founded on April 21st, 753 B.C. by a pair of twins named Romulus and Remus. When Remus made sport of Romulus’s still rudimentary defenses and leapt over them, he was killed for the slight, and so it was Romulus who gave his name to the city, became its first king, and established so many of its civic institutions, including its calendar and its religion.

As Ovid tells the story, Mars then prevailed upon Jupiter to deify Romulus:

“…he caught up Romulus, son of Ilia, as he was dealing royal justice to his people. The king’s mortal body dissolved in the clear atmosphere, like the lead bullet, that often melts in mid-air, hurled by the broad thong of a catapult. Now he has beauty of form, and he is Quirinus, clothed in ceremonial robes, such a form as is worthier of the sacred high seats of the gods.”

From then on, under the new name Quirinus, Romulus would be worshipped as a deity by the Romans. And April 21st, the putative day of the founding, continued to be celebrated throughout Roman history as the Natalis Urbis, the Birthday of the City. In A.D. 248, we hear that the reigning Emperor Philip the Arab celebrated the 1000th year anniversary of the city with “games of all kinds”.

But this was, perhaps, the last great celebration of the sort.

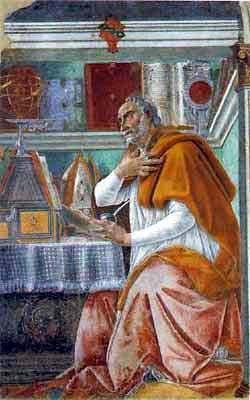

In the post-Constantinian era, as Christianity increasingly rivaled and then finally supplanted paganism, the character of Romulus came under increasing scrutiny. The Church Fathers repeatedly presented him as a man not worthy of emulation, much less deification, as we see in Augustine (City of God, 22:6), Tertullian, (De Spectaculis 5). Minucius Felix (Octavius, 25), and Lactantius (Divine Institutes, 20).

Augustine, as usual, is the most devastating in his rhetoric–not because he was the most polemical but because as a long-time admirer of Roman legends himself, he understood their flaws at a very deep level. With calm precision, and in his inimitable way, he contrasted the religion of Christ with the religion of Romulus:

For, not to mention the multitude of very striking miracles which proved that Christ is God, there were also divine prophecies heralding Him, prophecies most worthy of belief, which being already accomplished, we have not, like the fathers, to wait for their verification. Of Romulus, on the other hand, and of his building Rome and reigning in it, we read or hear the narrative of what did take place, not prediction which beforehand said that such things should be. And so far as his reception among the gods is concerned, history only records that this was believed, and does not state it as a fact; for no miraculous signs testified to the truth of this.

Christ was a more fitting deity than Romulus not only because He did the things that only a deity can do, but also because He was the fulfillment of a prophecy that long antedated Him. Augustine goes on to take apart the legend of Romulus piecemeal:

For as to that wolf which is said to have nursed the twin-brothers, and which is considered a great marvel, how does this prove him to have been divine? For even supposing that this nurse was a real wolf and not a mere courtesan, yet she nursed both brothers, and Remus is not reckoned a god.

Besides, what was there to hinder any one from asserting that Romulus or Hercules, or any such man, was a god? Or who would rather choose to die than profess belief in his divinity? And did a single nation worship Romulus among its gods, unless it were forced through fear of the Roman name?

He concludes his argument as follows:

And thus the dread of some slight indignation, which it was supposed, perhaps groundlessly, might exist in the minds of the Romans, constrained some states who were subject to Rome to worship Romulus as a god; whereas the dread, not of a slight mental shock, but of severe and various punishments, and of death itself, the most formidable of all, could not prevent an immense multitude of martyrs throughout the world from not merely worshipping but also confessing Christ as God.

In the late stages of an increasingly decadent Roman Empire, the Christian martyrs’ courage stood in stark opposition to the conduct of the age. Even though they served a different deity, the martyrs recalled by their courage a bygone Rome, appealing to those citizens who lamented the dissolution of the old Roman pietas that was in very short supply among their contemporaries.

Thus was the mind of pagan Rome opened to the revelation of Christ. And through her most famous martyrs of all, the Eternal City would inherit a new set of founding fathers to replace the ones they lost.

The New Founders

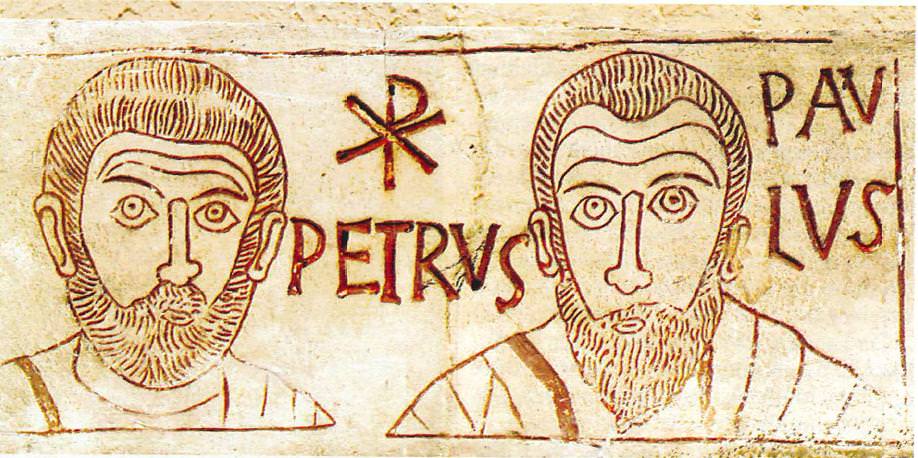

The Apostles Peter and Paul–a Galilean fisherman and a scholarly Pharisee–might be thought extremely unlikely candidates to replace Romulus and Remus. They were not even brothers in flesh, although they were brothers in Christ.

Yet they were very well situated for a Christian recalibration of the founding myth. As Pope St. Leo the Great said in his homily for their feast:

The whole world, dearly-beloved, does indeed take part in all holy anniversaries, and loyalty to the one Faith demands that whatever is recorded as done for all men’s salvation should be everywhere celebrated with common rejoicings. But, besides that reverence which today’s festival has gained from all the world, it is to be honoured with special and peculiar exultation in our city, that there may be a predominance of gladness on the day of their martyrdom in the place where the chief of the Apostles met their glorious end.

For these are the men, through whom the light of Christ’s gospel shone on you, O Rome, and through whom you, who was the teacher of error, was made the disciple of Truth. These are your holy Fathers and true shepherds, who gave you claims to be numbered among the heavenly kingdoms, and built you under much better and happier auspices than they, by whose zeal the first foundations of your walls were laid: and of whom the one that gave you your name defiled you with his brother’s blood.

These are they who promoted you to such glory, that being made a holy nation, a chosen people, a priestly and royal state, and the head of the world through the blessed Peter’s holy See you attained a wider sway by the worship of God than by earthly government. For although you were increased by many victories, and extended your rule on land and sea, yet what your toils in war subdued is less than what the peace of Christ has conquered.

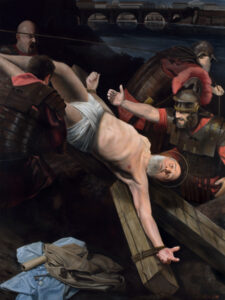

Even though Peter and Paul labored together in Rome, tradition has long maintained that they were martyred separately. The Prince of the Apostles died on the Vatican upon a cross. The Apostle to the Gentiles was beheaded along the Via Laurentina, as he was a citizen and could not be crucified.

One could certainly imagine a liturgical situation where St. Peter had his own feast and St. Paul had another completely separate one–but that is not what we see in the sources. Peter and Paul have been honored together on June 29th from time immemorial.

Dionysius, the Bishop of Corinth around the year 170, says that Peter and Paul “suffered martyrdom at the same time” (as quoted in Eusebius’s History of the Church II.25). But the passage does not offer any specific date. The actual feast day first appears in an ancient collection called the Chronography of 354, which contains a martyrology as well as a catalog of Popes. The first entry of the papal catalog is as follows:

Peter 25 years, 1 month, 9 days. He was in the times of Tiberius Caesar and Gaius and Tiberius Claudius and Nero, from the consulate of Minucius and Longinus [AD 30] to that of Nero and Verus [AD 55]. However he died with Paul on the 3rd day before the kalends of July, the emperor Nero being consul.

In the Depositionis Martyrum, a calendar of martyrs’ feasts in the same collection, the exact same date (the 3rd before the kalends of July) is given for Peter and Paul. Yet it also adds a puzzling note: “[during the] consulship of Tuscus and Bassus”. These two consuls are from A.D. 258, two centuries after Peter died. Some have surmised that the date must refer to a translation of the Apostles’ relics instead of their deaths, though there is also a Bassus who was consul under Nero in A.D. 64, complicating the matter.

As the papal catalog is meant as a historical document, its clear and explicit reference ought to command greater weight than an unclear reference mentioned as an aside in a liturgical calendar. Thus, considered together with the passage from Dionysius, it seems safest for history to side with the papal catalog that June 29th commemorates the actual deaths of Peter and Paul, and not merely a translation of their remains.

Finally, we cannot fail to mention another early tradition that is seen in St. Augustine (Sermo 295, 381), whereby Paul was indeed martyred on the same day as Peter, but not in the same year.

The Old Dates Prefiguring the New

So it was that Rome left off celebrating the date of founding by Romulus and Remus, and began celebrating Peter and Paul’s martyrdoms instead.

And perhaps Almighty God had already been preparing Romans for the transition through the natural course of history; sowing, long before Christ was even born, three seeds of the future Christian revelation into the ancient fabric of Italian paganism.

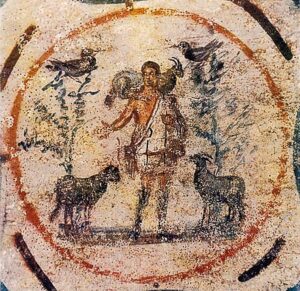

First, April 21st was not merely the secular date of Rome’s founding. It was also a religious festival called the Parilia, named for Pales, the god of shepherds and livestock, to whom the Romans prayed to keep the flocks fed and protected from diseases and wolves. Romulus and Remus’s association with shepherding was very strong; that was their occupation before they founded Rome, having inherited it from their foster-father, the shepherd Faustulus.

The season of the Parilia took on a deeper Christian meaning in the Roman Liturgy. Good Shepherd Sunday is the 2nd Sunday of Easter, which frequently falls around April 21st. The Epistle of St. Peter is read often in these early weeks of Eastertide, and at this Mass it anticipates the Gospel with the passage: “For you were as sheep going astray: but you are now converted to the shepherd and bishop of your souls.”

Thus, it would have been very natural for Roman Christians to see the Parilia as an anticipation not only of Christ the Good Shepherd but also Peter and his successors, who faithfully served their See with the words of the Risen Christ still resounding in their ears: “feed my lambs, feed my sheep.”

Second, on the Quirinal Hill there stood a temple dedicated to Quirinus/Romulus–said to be one of oldest temples in Rome, going to back to at least 293 B.C. and perhaps even earlier. At this temple was held the festival known as the Quirinalia, which took place annually on February 17th.

Note how close this date is to February 22nd, the second feast of the Chair of St. Peter. Despite its later associations with Antioch, this feast is Roman enough and ancient enough that it appears on the Chronography of 354. Christian Romans thus honored Peter in the very same week that their pagan counterparts honored Romulus, which no doubt strengthened the associations between the two.

Third is perhaps the most striking coincidence.

In 49 B.C., civil war was breaking out between Caesar and Pompey, and inauspicious portents like earthquakes and eclipses were alarming the Roman populace. The temple of Quirinus was consumed by fire. Lightning damaged a sceptre of Jupiter and a shield and helmet of Mars on the Capitol–the symbols of power of the very same gods who were said to have deified Romulus. To the Romans, it would have been crystal clear that divine wrath was falling on their city. And in hindsight, it looks rather like it was falling on their gods as well.

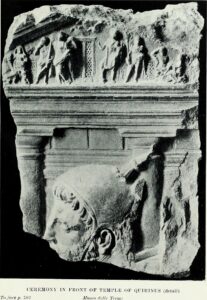

The temple of Quirinus was rebuilt and rededicated by Augustus in 16 B.C., and there remains to this day an ancient relief showing its restored pediment, with Romulus and Remus taking the auspices (image at right). This rededication occurred not during the traditional Quirinalia but in summer, after the Secular Games and just before Augustus left the city for Gaul. From Ovid we learn the exact date: the third day before the kalends of July.

Some sixteen years before the birth of Christ, roughly around the time that the Virgin Mary would likely have been born, the Romans began to celebrate a feast of their founders . . . on the 29th of June.

And they have been doing it ever since.

June 21, 2023