The Sacramentals of St. Blaise Day

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

Many Catholics are no doubt familiar with the blessing of throats performed on the feast of St. Blaise (February 3rd), one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, who miraculously healed “a boy, whose life was despaired of by the physicians, on account of his having swallowed a bone, which could not be extracted from his throat,” as it is stated in his biography from Matins.1 The blessing involves having blessed candles joined in the shape of a cross held to the throat while the Priest recites the following:

By the intercession of St. Blaise, bishop and martyr, may God deliver you from every malady of the throat, and from every possible mishap; in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, + and of the Holy Spirit. ℟. Amen.2

The use of candles as part of this blessing may have its origin in the following account: “Blaise met a poor woman whose only pig had been snatched up in the fangs of a wolf but at the command of the bishop the wolf restored the pig alive to its owner. The woman did not forget the favor, for later, when the bishop was languishing in prison, she brought him tapers to dispel the darkness and gloom.”3

But this blessing of throats is not the only special sacramental associated with the feast of St. Blaise. To begin with, one might think that these candles used in the throat blessing were blessed the day before, the Feast of Candlemas, but these candles have a unique (and long) blessing of the day applied to them. This blessing is as follows:

℣. Our help is in the name of the Lord.

℟. Who made heaven and earth.

℣. The Lord be with you.

℟. And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

God, almighty and all-mild, by Your Word alone You created the manifold things in the world, and willed that that same Word, by Whom all things were made, take flesh in order to redeem mankind; You Who are great and immeasurable, awesome and praiseworthy, a worker of marvels. Hence in professing his faith in You the glorious martyr and bishop, Blaise, did not fear any manner of torment but gladly accepted the palm of martyrdom. In virtue of which You bestowed on him, among other gifts, the power to heal all ailments of the throat. And now we implore Your majesty that, overlooking our guilt and considering only his merits and intercession, it may please you to bless + and sanctify + and impart Your grace to these candles. Let all men of faith whose necks are touched with them be healed of every malady of the throat, and being restored in health and good spirits let them return thanks to You in Your holy Church, and praise Your glorious name which is blessed forever; through Christ our Lord.

℟. Amen.

The candles are then sprinkled with holy water.4

The reference to Our Lord’s incarnation at the beginning of this blessing has a special significance in this context as the candle is seen as being a sign of the Incarnate Lord. In particular the wax is seen as representing His Body, the wick, His Soul, and the flame, His Divinity.

Lastly, there is the special blessing of bread, wine, water, and fruit in honor of the Saint for the relief of throat ailments. The blessing is as follows:

℣. Our help is in the name of the Lord.

℟. Who made heaven and earth.

℣. The Lord be with you.

℟. And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

God, Savior of the world, Who consecrated this day by the martyrdom of blessed Blaise, granting him among other gifts the power of healing all who are afflicted with ailments of the throat; we humbly appeal to your boundless mercy, begging that these fruits, bread, wine, and water brought by Your devoted people be blessed + and sanctified + by Your goodness. May those who eat and drink these gifts be fully healed of all ailments of the throat and of all maladies of body and soul, through the prayers and merits of St. Blaise, bishop and martyr. We ask this of You Who live and reign, God, forever and ever.

℟. Amen.

The items are then sprinkled with holy water.5

While this blessing is only to be performed on the feast of St. Blaise, the blessed items can be saved and consumed as needed throughout the year.

In addition to receiving the yearly blessing of throats, the faithful, especially those who are prone to ailments of the throat, are also encouraged to take advantage of this unique blessing of bread, wine, water, and fruit. Of course, it is best to coordinate this with one’s priest ahead of time.

Fr. Wiliam Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

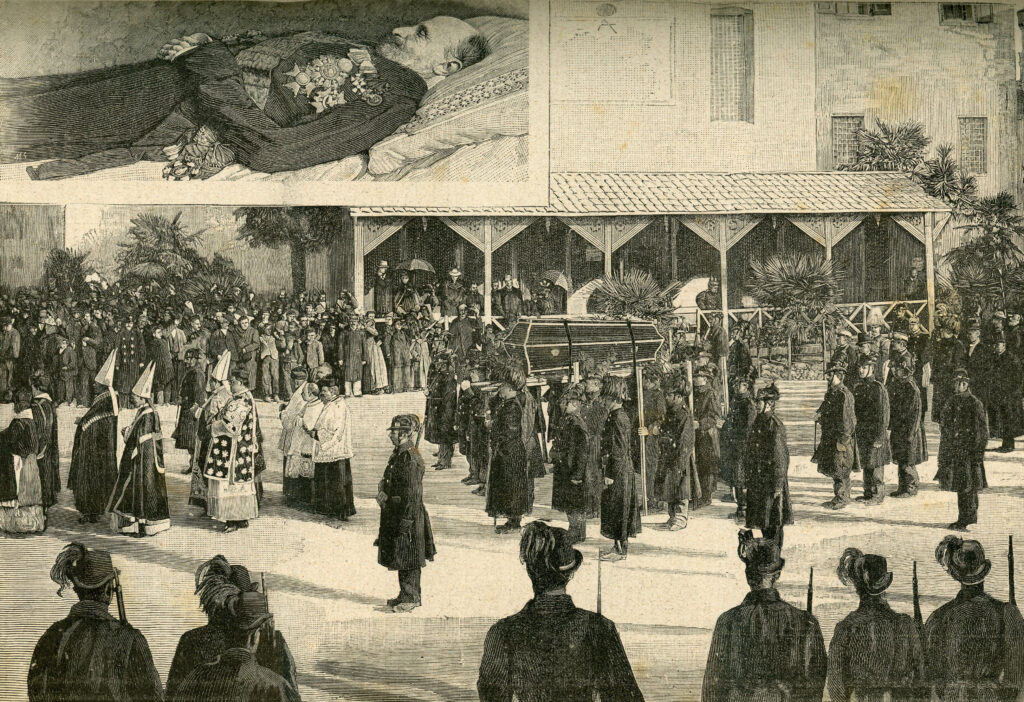

In support of the causes of Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen, and Servant of God Francesco II, King

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, vol. 4 (Septuagesima). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), p. 236.

- Latin original Rituale Romanum, Titulus IX – Caput 3, 7; English adopted from the Weller translation of the Roman Ritual provided online by EWTN.

- From the Weller translation of the Roman Ritual provided online by EWTN, “Chapter II: Blessings for Special Days and Feasts of the Church Year, 10.”

- Rituale Romanum, Titulus IX – Caput 3, 7; English adopted from the Weller translation provided online by EWTN.

- Rituale Romanum, Titulus IX – Caput 3, 8; English adopted from the Weller translation provided online by EWTN.

January 29, 2024

The Blessed Karl of Southern Italy

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

Many readers of the Missive are no doubt aware of the devotion found in traditional circles to Blessed Karl of Austria and his wife, Servant of God Zita. This devotion is founded primarily on the recognition of their virtues, but there is the strong influence of what they represent. As the last Catholic Emperor and Empress, their lives and deaths represent a delineation between a previous order of the world and the present one. As the last monarchs of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, their unjust and forced dethronement is seen as the death of Christendom, the spirit of which many traditional Catholics prefer over the spirit which pervades the world today. For the spirit of Christendom built civilizations, guided nations, and allowed the Catholic Faith to penetrate and infuse every aspect of the faithfuls’ lives.

There is little doubt that Blessed Karl and his devotees would find a kindred spirit in Servant of God Francesco II1 of the House of Bourbon, the last King of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. He ruled over a kingdom which encompassed the southern part of the Italian peninsula and the island of Sicily. This territory was first organized as a kingdom in A.D. 1130 with the crowning of the first King of Sicily, the Norman Roger II. Yet the foundation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Il Regno, are rooted deep in history, going back from the time of Roger II to the various, prior districts governed by the Lombards, Normans, Byzantines, and Muslims, to the former provinces of the Roman Empire, and finally back to the original Greek colonies of Magna Græcia and the settlements of the Phoenicians.

For his part, Francesco d’Assisi Maria Leopoldo was born on 16 January 1836 to King Ferdinando II and Queen Maria Cristina of Savoy, (herself a Blessed whose “religious devotion was legendary”2). The Queen died “in 1836 from complications giving birth to her only child.”3 Having lost his mother so soon after his birth, Francesco turned to the Blessed Virgin Mary and developed a strong, filial devotion to her. His education was overseen by the priests and members of the court. “Like his mother, Francesco was very devout, thought by many to be more seminarian than soldier.”4

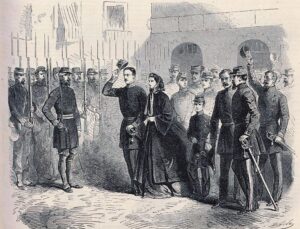

After his father’s death, Francesco II ascended the throne of Il Regno on 22 May 1859 at 23 years of age. The first year of his reign was one of great activity – projects, improvements, and reforms – undertaken for the sake of his citizens and the good of the Kingdom. But, the French Revolution still casting its long shadow, his benevolent and industrious reign was fated to be short. In May 1860, colluding with and aided by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (located in its insular namesake and the north of the Italian peninsula) and with the assistance of the British, Giuseppe Garibaldi’s Expedition of the Thousand landed in western Sicily. In August of the same year, Garibaldi’s troops crossed over to the mainland, bribing officials to treason along the way. Out of love for his people and their patrimony, in early September, Francesco withdrew from Naples, the capital city, to the fortress of Gaeta, located on the western coast midway between Naples and Rome, where he and his wife, Queen Maria Sophia of Bavaria, having left behind their personal wealth and belongings, took refuge with 20,000 troops. Francesco himself fought on the walls with his men while his wife served as a nurse. After several months of siege and bombardment, on 13 February 1861, faced with impossible odds, the fortress surrendered. On 14 February 1861, the King and Queen left the fortress among the tears of their troops, who remained loyal until the end, with a military farewell. They were received aboard a ship waiting in the harbor, and the flag of Il Regno was struck.

Francesco II lived the rest of his life in exile, first in Rome and then, after Rome itself was taken by Piedmontese forces, in Paris and Vienna, with his latter days in Arco. During his exile, he was well-known for his generosity to those in need – no one went away without some assistance. He spent his last days simply in Arco, his royal personage concealed. In the mornings he would attend daily Mass and, in the evenings, return to the church to pray the rosary in common. “Francesco died in Arco, in Trent, then part of Austria”5 on 27 December 1894, the Feast of St. John the Apostle. It is fitting that one who adopted the Blessed Virgin as his mother die on the feast of him to whom Our Lord entrusted His mother while hanging on the cross.

Like Karl of Austria, Francesco II was unjustly and forcefully removed from his throne and lived the rest of his life in exile. But also like the good Emperor, the good King is distinguished more for his Christian faith and virtue than for his royalty. Among the testimonies to his virtue, may it suffice here to quote one of Francesco’s descendants, Charles of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, Duke of Castro, to illustrate the truth of the matter:

Francis II had a varied and complex personality. In the few months of his reign, he was unable to put an end to a crisis which had begun far away, of which he had been bequeathed the difficult inheritance. But still, throughout the course of his life, he knew how to give ample proof of total closeness and identification with the peoples he governed. Not only because he prevented the destruction of Naples.

Giving precise orders to the garrisons present in the city to not shoot upon the arrival of Garibaldi’s troops, but above all, during the battle of Volturno and the following siege of Gaeta, he did so in a way that none of the prisoners, Garibaldi’s men first, and then the Piedmontese, would be treated villainously, as was then the practice among the troops fighting him.

Deeply Catholic, Francis II made of Christian doctrine a doctrine of life, always relieving the sufferings of his people, even following the fall of his Kingdom. And, although restricted economically, his aid was never lacking to those who asked him for it. He always had the dignity of a King.

And throughout his life, made up of mourning and suffering, the least of which was the loss of his only and most beloved daughter, Maria Christina, he faced all of these trials with Christian patience. So much so, to cause Pius IX to say that Francis II resembled a little “Job.”

If you, dear reader, are moved in any way by the preceding, consider taking on the Servant of God Francesco II as a patron, or, perhaps, his mother, Blessed Maria Cristina, as a patroness. And further, if you are so convicted, request a favor through his (or her) intercession, so that God may, by the working of miracles through his (or her) patronage, soon raise them, along with Karl and Zita, to the altars –these last saints of Christendom.

Blessed Karl of Austria, Pray for us!

Blessed Maria Cristina, Pray for us!

Servant of God Francesco II, Pray for us!

Servant of God Zita, Pray for us!

Favors obtained through the intercession of Servant of God Francesco II can be submitted to his Postulation by mail at “Service for the Causes of Saints, Largo Donnaregina 22 – 80138 – Naples (NA), Italy” or by email at postulazione@francescosecondodiborbone.it.

Prayer to Servant of God Francesco II

One and Triune God, Who casts Your glance on us from Your throne of mercy, and called Francis II of Bourbon to follow You, choosing him on earth to be king, modeling his life on the very Kingship of Jesus Christ, crucified and risen, pouring into his heart sentiments of love and patience, humility and meekness, peace and pardon, and clothing him with the virtues of faith, hope and charity, hear our petition, and help us to walk in his footsteps and to live his virtues. Glorify him, we pray You, on earth as we believe him to be already glorified in Heaven, and grant that, through his prayers, we may receive the graces we need. Amen.

A League of Prayer and Charity has also been established to promote the cause of Servant of God Francesco II and to aid his devotees in imitating his virtues.

Favors obtained through the intercession of Blessed Maria Cristina can be submitted to her Postulation by mail at “Postulation of the Cause, Via Santa Maria Mediatrice, 25, 00165 Rome, Italy” or by email at postgen@ofm.org.

Prayer to Blessed Maria Cristina

Let us pray: O God, You adorned Blessed Maria Cristina with diligent and wise charity, so that by her witness, she would contribute to the building up of Your Kingdom. Grant us also by her example, to do good, drawing on the true riches of Your Love. Through her intercession, grant us the grace of […] which we ask with confidence. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

Holy Cards of Blessed Maria Cristina and of Servant of God Francesco II can be obtained by contacting info@smocsg.org.

Additional information about the Servant of God Francesco II can be found in this episode of the Italian American Podcast. Those who can read Italian may be interested in the book Francesco II, Il Re Cattolico.

In conformity with the decrees of Pope Urban VIII, in no way is this article intended to anticipate the ecclesiastical authority; the above prayers are not intended for public use.

Fr. Wiliam Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- His name might also be rendered as Francis II in English, as presented in a quote later in the article. I have chosen to use Francesco, which follows the usage of author Louis Mendola.

- Mendola, Louis. The Royal House of the Two Sicilies: An Introduction to the Orders of Chivalry. (New York: Trinacria Editions; copywrite New York: American Delegation of Sacred Military Constantinian Order of St George Naples Two Sicilies Inc, New York, 2021), p. 46.

- Ibid., p. 46.

- Ibid., p. 48.

- Ibid., p. 49.

December 27, 2023

“Fear Not: For on the Fifth Day, Our Lord Shall Come Unto You”

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

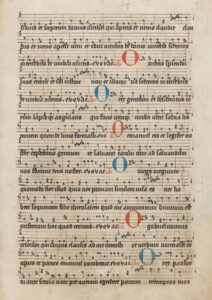

The Greater Ferias of Advent, December 17th to 23rd, the final days of Advent, are set aside by Holy Mother Church to serve as a proximate preparation for the Nativity of the Lord. The most noted feature of these days is the “Great Antiphons” or the “O Antiphons” (as they all start with “O”) sung at Vespers in the evening of each of these Greater Ferias. Each of these Magnificat antiphons invokes the Messias under a different title: Sapientia (Wisdom), Adonaï (Lord), Radix Jesse (Root of Jesse), Clavis David (Key of David), Oriens (Orient / Day-spring), Rex Gentium (King of the Nations / King of the Gentiles), and lastly Emmanuel (Emmanuel / God is with us). These antiphons form the basis of the Advent hymn O Come, O Come Emmanuel. But these O Antiphons are not the only point of interest during this time.

On the morning of December 21st, the Feast of St. Thomas, the following Antiphon is prayed after the oration of the Apostle as part of the commemoration of the Greater Feria: “Nolíte timére; quinta enim die véniet ad vos Dóminus noster / Fear not: for on the fifth day, Our Lord shall come unto you [plural].”1 It should be noted that the fifth day is to be determined by counting inclusively, which is how the Romans and Hebrews counted. This means December 21st is the first day, the 22nd, the second, and so on until the fifth day, December 25th, Christmas Day. But even understanding this, the antiphon is still mysterious. Unfortunately, no interpretation is provided either by William Durandus, the great medieval liturgical commentator, or by Dom Prosper Guéranger (although the latter does provide the text).

To begin with, the question can be asked: why the fifth day and not another? As the antiphon is not a direct quote from Sacred Scripture, there is no direct scriptural context which can serve as basis for the interpretation. Five days, however, does enter into the story of Judith. Fearing the might of the army of Holofernes, Ozias, the prince of Juda, promised to surrender if God did not deliver them within five days (Jdt 7:23). Upon hearing of this, Judith rebuked this tempting of God, but yet said to elders Chabri and Charmi, “You shall stand at the gate this night, and I will go out with my maidservant: and pray ye, that as you have said, in five days the Lord may look down upon his people Israel” (Jdt 8:32). After preparing herself spiritually and physically, Judith and her maid went out of the city to the enemy camp. She was received favorably by the general and given a degree of freedom. On the fourth day (Jdt 12:10), Judith was invited into Holofernes’ tent, an invitation which she accepted. That evening, Judith beheaded Holofernes, and it was on the fifth day that the army, realizing that Holofernes was dead, fled in retreat. So it was that God did indeed deliver His people on the fifth day, unexpectedly, by the hand of a woman.

Now, according to Dr. Nathanael Schmiedicke’s Handy Guide to Biblical Numerology, the number five can be seen as representing “unexpected victory / salvation / life / blessing.” In support of this, Dr. Schmiedicke explains that David had five stones when he defeated Goliath (1 Kin [Sam] 17:40), which was certainly an unexpected victory. Additionally, “Day 5 of creation is the first one to use the word for ‘soul’ and for ‘living’ to describe water and air animals (Gen 1:20). Also, this is the first day God blesses anything (Gen 1:22).” This interpretation of the number five fits well with the story of Judith, for God brought about through her an “unexpected victory,” which brought salvation and life to the Hebrew people, as well as material blessings in the spoils taken from the fleeing enemy’s camp.

Using this Biblical-numerical interpretation of five and the story of Judith, the Lauds antiphon under consideration can be read as follows: “Fear not the enemies which surround you and threaten your destruction: for on the fifth day, Our Lord shall come unto you and will bring about something unexpected through a woman, the true Judith, the Virgin birth of the Incarnate Son of God Who will win a victory which will bring salvation to His people, meriting for them the life of grace and other blessings.”

Additionally, it is worth noting that December 21st is the typical date of the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere, the day with the shortest amount of sunlight each year (and also the start of astronomical winter).s It is fitting, then, that the Great Antiphon for this evening is O Oriens (O Orient! splendor of eternal light, and Sun of justice! come and enlighten those sitting in darkness, and in the shadow of death).3 For, from this day forward, from the singing of the O Antiphon evoking Our Lord as the Orient (Day-spring / Dawn / Sunrise), the amount of daylight per day will steadily increase. As such, there is a fittingness of having the comfort of the Nolíte timére Antiphon also on this day when the darkness of night, symbolizing evil, seems to triumph over the light of day, symbolizing goodness. With this in mind, the Lauds antiphon can be read as follows: “Fear not the seeming triumph of the darkness of evil: for on the fifth day, Our Lord, the Orient, the splendor of eternal light, and Sun of justice, shall come to unto you to enlighten those sitting in darkness, and in the shadow of death.”

May these thoughts accompany the faithful, who fear not the darkness of evil, as they make their final preparations, both spiritually and physically, for the approaching Feast of the Nativity of their Lord.

Fr. Wiliam Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, vol. 1 (Advent). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), p. 494.

- “At the time of the Julian reform [of the calendar] the sun passed the vernal equinox on 25 March, but by the time of the Council of Nicæa (A.D. 325) this had been changed for the 21st” of March (Old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Reform of the Calendar”). Presuming this shift also effected the winter solstice (moving the date from 25 December [see Guéranger, Advent, pp. 308-309] to 21 December), and also presuming that the O Antiphons were “known and used as early as the beginning of the sixth century [A.D. 500s]” (Cabaniss, J. Allen. Liturgy and Literature – Selected Essays. “A Note on the Date of the Great Advent Antiphons”. [University of Alabama, 1970], p. 100), the O Oriens Antiphon would have always been associated with the 21 December winter solstice date. Perhaps the Nolíte timére Antiphon was assigned this date to also specifically coincide with the 21 December winter solstice.

- See Guéranger, p. 500.

December 21, 2023

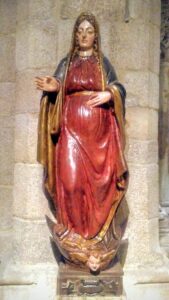

Mass of the Expectation of the Blessed Virgin Mary

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

In editions preceding the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal, in the section for Masses for particular places (Missæ Pro Aliquibus Locis), listed for December 18th, is the Mass of the Expectation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (In Exspectatione Partus B. Mariæ Virg.). In the Advent Volume of his Liturgical Year, Dom Prosper Guéranger explains the origin of this Mass, its associated Feast, and how it was kept as follows:

This feast, which is now kept not only throughout the whole of Spain but in many other parts of the Catholic world, owes its origin to the bishops of the tenth Council of Toledo, in 656. These prelates thought that there was an incongruity in the ancient practice of celebrating the feast of the Annunciation on the twenty-fifth of March, inasmuch as this joyful solemnity frequently occurs at the time when the Church is intent upon the Passion of our Lord, so that it is sometimes obliged to be transferred into Easter time, with which it is out of harmony for another reason; they therefore decreed that, henceforth, in the Church of Spain there should be kept, eight days before Christmas, a solemn feast with an octave, in honour of the Annunciation, and as a preparation for the great solemnity of our Lord’s Nativity. In course of time, however, the Church of Spain saw the necessity of returning to the practice of the Church of Rome, and of those of the whole world, which solemnize the twenty-fifth of March as the day of our Lady’s Annunciation and the Incarnation of the Son of God. But such had been, for ages, the devotion of the people for the feast of the eighteenth of December, that it was considered requisite to maintain some vestige of it. They discontinued, therefore, to celebrate the Annunciation on this day; but the faithful were requested to consider, with devotion, what must have been the sentiments of the holy Mother of God during the days immediately preceding her giving Him birth. A new feast was instituted, under the name of “the Expectation of the blessed Virgin’s delivery.”

This feast, which sometimes goes under the name of Our Lady of O, or the feast of O, on account of the great antiphons which are sung during these days, and, in a special manner, of that which begins O Virgo virginum (which is still used in the Vespers of the Expectation, together with the O Adonai, the antiphon of the Advent Office), is kept with great devotion in Spain. A High Mass is sung at a very early hour each morning during the octave, at which all who are with child, whether rich or poor, consider it a duty to assist, that they may thus honour our Lady’s Maternity, and beg her blessing upon themselves. It is not to be wondered at that the holy See has approved of this pious practice being introduced into almost every other country. We find that the Church of Milan, long before Rome conceded this feast to the various dioceses of Christendom, celebrated the Office of our Lady’s Annunciation on the sixth and last Sunday of Advent, and called the whole week following the Hebdomada de Exceptato (for thus the popular expression had corrupted the word Expectato). But these details belong strictly to the archaeology of liturgy, and enter not into the plan of our present work; let us, then, return to the feast of our Lady’s Expectation, which the Church has established and sanctioned as a new means of exciting the attention of the faithful during these last days of Advent.1

The Great Antiphon to Our Lady

O Virgo virginum, quomodo fiet istud? quia nec· primam similem visa es, nec habera sequentem. Filiae Jerusalem, quid me admiramini? Divinum est mysterium hoc quod cernitis.

O Virgin of virgins, how shall this be? for never was there one like thee, nor will there ever be. Ye daughters of Jerusalem, why look ye wondering at me? What ye behold, is a divine mystery.2

The Mass3 itself opens with the chant Rorate Caeli (Isa 45:8): “Drop down dew, ye heavens, from above, and let the clouds rain the just: let the earth be opened, and bud forth a saviour.” This is a prophecy of Christ, the Just One Who comes from Above, and the Blessed Virgin, who will give birth to the Savior. In addition to being the opening chant of several Masses during Advent, the text is also ubiquitous in the Office of the season. The Psalm verse is Psalm 18:2: “The heavens shew forth the glory of God, and the firmament declareth the work of his hands.” While this verse seems out of place, as it refers symbolically to the Apostles, it must be remembered that this is only the start of the Psalm and, as such, is meant to call to mind its entirety. Later on, verse 6 reads: “He hath set his tabernacle in the sun: and he as a bridegroom coming out of his bridechamber, Hath rejoiced as a giant to run the way.” It is very common for the womb of the Blessed Virgin to be seen as the bridechamber where God the Son entered into a nuptial relationship with humanity by assuming a Human Nature.4 The Common of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Divine Office makes use of this Psalm in the first Nocturne. The Psalm verse sets this Mass proper apart from the Rorate Mass chant for the Saturdays during Advent (which uses Ps 84:2), but is the same as that used in the Rorate Introits of Ember Wednesday of Advent and of the Fourth Sunday of Advent.

The Collect (opening prayer) reads as follows:

Deus, qui de beátæ Maríæ Vírginis útero Verbum tuum, Angelo nuntiánte, carnem suscípere voluísti: præsta supplícibus tuis; ut, qui vere eam Genetrícem Dei crédimus, ejus apud te intercessiónibus adjuvémur. Per eúndem Dóminum…

O God, Who, by the message of an angel, willed Your Word to take flesh in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, grant that we, Your suppliants, who believe her to be truly the Mother of God, may be helped by her intercession with You. Through the same Our Lord…5

This is the same as the Collects in the Mass of the Annunciation and in the Saturday Rorate Mass.

The Epistle is the prophecy of the Virgin Birth found in the seventh chapter of the Book of the Prophet Isaias (Isa 7:10-15), the same used on the Feast of the Annunciation, Ember Wednesday of Advent, and the Saturday Rorate Mass.

The Gradual is taken from Psalm 23:7, 3-4: “Lift up your gates, O ye princes, and be ye lifted up, O eternal gates: and the King of Glory shall enter in. ℣. Who shall ascend into the mountain of the Lord: or who shall stand in his holy place? The innocent in hands, and clean of heart.” The first part, in this context, would seem to indicate the preparation the world should be undertaking to prepare for the One soon to be born, soon to enter into this world. The second part describes the perfections of the One Who is to Come. These lines are also the Gradual for the Ember Wednesday during Advent, and Psalm 23:7 is the text of the Offertory of the Mass of the Vigil of Christmas.

The Alleluia alludes to the prophecy heard in the Epistle and Luke 1:31: “Behold, a Virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, Jesus Christ.” While similar to others, this chant, due to its conclusion, is unique.

The Gospel is the account of the Annunciation found in the Gospel of Luke (1:26-38), the same used on the Feast of the Annunciation, Ember Wednesday of Advent, and the Saturday Rorate Mass.

The Offertory chant is also taken from the Gospel of Luke (1:28, 42), combining the greetings of the Archangel Gabriel and Mary’s kinswoman Elizabeth: “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women: blessed art thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb.” This is the familiar beginning of the Hail Mary. The same chant is used as the Offertory for the Feast of the Annunciation, the Saturday Rorate Mass, and the Fourth Sunday of Advent.

The Secret (prayer over the gifts) is the same as that prayed on the Feast of the Annunciation and the Saturday Rorate Mass:

In méntibus nostris, quǽsumus, Dómine, veræ fídei sacraménta confírma: ut, qui concéptum de Vírgine Deum verum et hóminem confitémur; per ejus salutíferæ resurrectiónis poténtiam, ad ætérnam mereámur perveníre lætítiam. Per eúndem Dóminum nostrum….

Fix firmly in our minds, O Lord, we beseech You, the mysteries of the true faith; that we who believe Him, conceived of a Virgin, to be true God and man, may be found worthy to reach eternal happiness through the power of His redeeming resurrection. Through the same Our Lord…

The Communion chant is taken from the Isaias’ Prophecy (Isa 7:14): “Behold a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son and his name shall be called Emmanuel.” The same is used on the Feast of the Annunciation, Ember Wednesday of Advent, the Fourth Sunday of Advent, and the Saturday Rorate Mass.

The Postcommunion (closing prayer) is familiar as the prayer used in the Angelus:

Grátiam tuam, quǽsumus, Dómine, méntibus nostris infúnde: ut, qui, Angelo nuntiánte, Christi, Fílii tui, incarnatiónem cognóvimus; per passiónem passiónem ejus et crucem, ad resurrectiónis glóriam perducámur. Per eúndem Dóminum…

Pour forth, we beseech You, O Lord, Your grace into our hearts, that we, to whom the incarnation of Christ, Your Son, was made known by the message of an angel, may, by His passion and cross, be brought to the glory of the resurrection. Through the same Our Lord…

This prayer is also used as the Postcommunion in the Mass of the Annunciation and the Saturday Rorate Mass.

Besides the Alleluia, the Mass of the Expectation of the Blessed Virgin Mary shares many propers with the Marian Masses of the Annunciation and the Rorate Mass of Our Lady on Saturdays during Advent along with the Masses of Ember Wednesday in Advent (which itself also commemorates the Annunciation) and the Fourth Sunday in Advent. So, while the texts of this Mass are not overly unique, it is the spirit associated with the Mass which sets it apart, a spirit captured by Dom Guéranger in the lines already quoted above and expressed in the form of the below prayer to Our Lady.

Most just indeed it is, O holy Mother of God, that we should unite in that ardent desire thou hadst to see Him, who had been concealed for nine months in thy chaste womb; to know the features of this Son of the heavenly Father, who is also thine; to come to that blissful hour of His birth, which will give glory to God in the highest, and, on earth, peace to men of good-will. Yes, dear Mother, the time is fast approaching, though not fast enough to satisfy thy desires and ours. Make us redouble our attention to the great mystery; complete our preparation by thy powerful prayers for us, that when the solemn hour has come, our Jesus may find no obstacle to His entrance into our hearts.6

Fr. Wiliam Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, vol. 1 (Advent). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), pp. 588-486.

- Ibid., p. 490

- The Propers of the Mass were taken from this edition of the Roman Missal.

- See, for example, Guéranger’s Advent, p. 156.

- Translations of the orations are taken from The Divinum Officium Project.

- Guéranger, pp. 489-490.

December 18, 2023

Fr. James Buckley, FSSP 1937-2023

A Solemn Requiem Mass for Fr. Buckley will be held at 11am on Friday, December 22nd at Christ the King Church in Dallas, Texas, with burial to follow at a later date at OLGS in Nebraska.

Fr. James Bartholomew Buckley was born on November 29, 1937, in New York City. His parents, John Francis Buckley and Mary Catherine Lyons were Irish immigrants from County Galway.

He attended St. Luke’s grade school in the south Bronx, graduating in June 1951. In the fall of 1951, he entered Mother of the Savior, a Junior Seminary run by the Salvatorian Fathers in Blackwood, New Jersey. After graduating in May 1957, he entered the Salvatorian Novitiate in Colfax, Iowa on September 7th, 1957. After professing his first religious vows on September 8th, 1958, he began his studies in Philosophy at the Catholic University of America. Upon obtaining his B.A. in 1960, he taught Freshman Latin & English for one year at Francis Jordan High School in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. On June 5th, 1965, having completed his study of Theology at Catholic University, he was ordained a priest at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington D.C.

From the fall of 1965 to the spring of 1967, Fr. Buckley taught English and Religion at St. Mary’s High Scholl in Lancaster, New York (Diocese of Buffalo). For the next three years, he taught English, Religion and College Composition at St. Pius X, the Junior Seminary for the Diocese of Sacramento.

From September 1970 to June 1975, Fr. Buckley was a missionary in Southern Tanzania where for two years he administered a parish with three mission stations in the Diocese of Nachingwea. After obtaining his master’s degree in English, he spent the next two years teaching English, Math, and General Paper at the Junior Seminary in Likonde operated by the Benedictine Fathers.

After returning to the states in 1975, Fr. Buckley was an Assistant Pastor at St. Marks Parish in Phoenix, Arizona for two years. He next taught English and Religion from 1977 to 1980 at Bishop Manogue High School in Reno, Nevada. He was the Administrator of St. Margaret of Cortona Parish in Big Lake, Texas for 10 months and then became an Assistant at St. Mary’s in Ft. Worth, Texas. From 1981 to 1985, he was an Assistant for a year at each of the fallowing parishes in the Diocese of Arlington, Virginia: St. Thomas More Cathedral, Our Lady of Fatima, St. Michael, and St. William of York. In 1986, he taught at Seton School in Manassas, Virginia while residing at All Saints rectory.

From the summer of 1987 to the summer of 1992, Fr. Buckley lived with the Fathers of Mercy, preaching Missions and Retreats. On July 5th, 1992, Fr. Buckley joined the Fraternity of St. Peter. For the next two years, he was the Administrator of Mater Dei, the Latin Mass community in Dallas, Texas. From 1994 to the spring of 2016, he taught various courses at Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary, where he served as Spiritual Director. During this time, he wrote a monthly column for the Fraternity Newsletter, published articles and book reviews in Homiletic and Pastoral Review, and conducted the spiritual exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola. He also wrote some booklets including the following titles: You Are Peter, Purgatory, The Real Presence, A Catechism for Making a Good Confession, Miracles, and Collected Articles.

Because of glaucoma and macular degeneration in his right eye, he retired in the spring of 2016. He lived for one year at the Fraternity Apostolate in Fort Wayne, Indiana, before moving to his final assignment in Mater Dei in Irving, Texas.

Please pray for the repose of Father’s soul.

December 15, 2023

Fr. Rock’s Extraordinary Thoughts liturgical guides

Advent is a great time to refresh your memory on the traditional liturgical year!

Fr. William Rock has written an excellent set of Extraordinary Guides to the various church seasons, available on our website here:

December 6, 2023

Rorate Mass at the National Shrine of Saint Alphonsus Liguori

Holy Mother Church has given us the tradition of the Rorate Mass, on a Saturday of Our Lady, in the midst of Advent as an opportunity to contemplate the mystery of darkness and light. Outside, all the world lies in darkness while, inside, the candlelight leaps into the shadows and overpowers them.

We may feel like the darkness of sin and indifference, like the darkness of the troubles that plague our world, our nation, and our Church, threaten to overwhelm and destroy the Light of Christ. But darkness does not overcome light. The light of just one candle is enough to dispel darkness. Imagine the power of the Light of the World!

The Rorate Mass is a visible, burning reminder to us that, by our prayers and offerings, we are to awake the dawn of Christ in our own lives. By vigilantly tending our own flames of faith, of prayer, and of penance, we burn out all inside of us that is not of Him. The candles on our altar, offered by our faithful, are a reminder to us that these spiritual flames are the only real weapons that have any power over the darkness.

It takes days to set up all the candles in the Shrine of Saint Alphonsus Liguori before Rorate. Hundreds of tiny, flickering flames set the altar and sanctuary aglow. But it is a joyful, spiritual labor, because their light in the darkness is a reminder of the Divine Flame that burns inside our hearts, even in a dark world.

Offer a candle to Our Lady this year for your particular intentions. The Rorate Mass will be offered for those intentions enrolled. And the candles that burn for those intentions will continue to bear your prayers to Heaven for seven days and nights. Unite your prayers to our Lady’s at this year’s Rorate Mass by lighting a candle. Together, let us awake the Dawn, hidden just beyond the horizon: https://stalphonsusbalt.org/rorate

Watch the live broadcast of High Mass from the Shrine, featuring Tomás Luis de Victoria’s Missa Alma Redemptoris Mater and his motet Alma Redemptoris Mater, as well as Ola Gjeilo’s Ave Generosa, beginning just before dawn at 6 am on Saturday, 9 December:

https://youtu.be/-m0rRHNT0JQ

December 4, 2023

Video: Christ the King Procession in El Paso

Immaculate Conception Church in downtown El Paso Texas is the Pro-Cathedral of El Paso, meaning that it was the first Cathedral of the diocese until St. Patrick’s Cathedral was finished. Build in 1893, the FSSP has had charge over this historic church since 2014 at the invitation of Bishop Mark Seitz.

This year the parish community has hosted a number of events in honor of the 130th anniversary of the Church, including a Eucharistic Procession on the Feast of Christ the King.

Over 400 people attended Solemn Mass and the procession through the streets of the city, which included Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament in San Jacinto Plaza, the central plaza of downtown El Paso. Over a mile long the procession was attended by faithful from around the city who came together to honor Christ our King and witness to their fidelity to his kingdom.

A faithful parishioner made a beautiful video to honor the occasion that we want to share with you. Never forget that, in the midst of worry and discouragement, there are still many faithful hearts who strive to offer beautiful tributes of worship to our God and to witness to His love.

Que viva Cristo Rey! Que viva la Virgen de Guadalupe!

Immaculate Conception FSSP Feast of Christ the King Procession, Downtown El Paso, TX from Paul Sandoval on Vimeo.

November 27, 2023

Requiem Masses after the Day of Burial

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

From the very foundation of Christianity, Masses and prayers have been offered up for the repose of the souls of the departed.1 In the Roman tradition, this practice developed into the various Requiem Masses, prayers, and other suffrages for the dead. Named after the first word of the Introit (entrance chant), a Requiem Mass is a Mass whose focus is the repose of the soul (or souls) of the departed. The Requiem Mass is, therefore, a Mass for the dead. All of the Requiem Masses share the same chants (Introit, Gradual, Tract, Sequence, Offertory, and Communion), but the orations (Collect, Secret, and Postcommunion) and readings (Epistle and Gospel) vary. There are Requiem Masses for the Day of Death or Burial, three for All Souls Day, on the Anniversary Day of the Death or Burial, the daily Mass for the Dead, and those for the Third, Seventh, and Thirtieth Day after the Burial.

The Requiem Masses which can be offered on the third, seventh, and thirtieth days after the burial are the same as the Mass of the Day of Burial (Epistle: 1 Thess. 4:13-18; Gospel: John 11:21-27) with the following orations:2

(Collect) We beseech Thee, O Lord, that Thou wouldst vouchsafe to grant fellowship with Thy saints and elect to the soul of the Thy servant (or handmaid) N., the third (or seventh or thirtieth) day of whose burial we commemorate, and wouldst pour out the everlasting dew of Thy mercy. Through Our Lord…

(Secret) Look favorably, we beseech Thee, O Lord, upon the offerings we make on behalf of the soul of Thy servant (or handmaid) N., that cleansed by heavenly remedies, it may rest in Thy mercy. Through Our Lord…

(Postcommunion) Receive our prayers, O Lord, on behalf of the soul of Thy servant (or handmaid) N., that if any stains of earthly contagion remain, they may be washed away by Thy merciful forgiveness. Through Our Lord…

Offering Masses on these days for the departed is very ancient and symbolic reasons have been given for their celebration.3 “With regard to the third day, as commemorative of the three days which Christ passed in the sepulcher, and as presaging the Resurrection, there is special prescription in the Apostolic Constitutions [4th Century] (VIII, xlii): ‘With respect to the dead, let the third day be celebrated in psalms, lessons, and prayers, because of Him who on the third day rose again.’”4 Evidence of the Masses offered on the seventh and thirtieth day is found in the works of St. Ambrose (d. A.D. 397): “Now, since on the seventh day, which is symbolical of eternal repose, we return to the sepulchre”5 (De fide. resurr.), and

Because some people are accustomed to observe the third and thirtieth day and some the seventh and the fortieth, let us look closely at what the text of Scripture teaches. When Jacob died, it says, Joseph instructed the undertakers in his service to bury him. And they buried Israel. And forty days were completed for him; for this is how the days of the funeral rites are reckoned. And Egypt mourned him for seventy days [Gen 50:2-3 according to the Itala]. This, then, is the observance to be followed, which is set out in the text. But equally, in Deuteronomy it is written that the children of Israel mourned Moses for thirty days and the days of mourning were completed [Deut. 34:8 according to the Itala]. So either observance has the authority through which the duty required of filial piety is fulfilled. (De ob. Theodosii, iii)6

In the Roman tradition, then, the Mass on the third day can be seen as being done in honor of the days Our Lord’s Body rested in the tomb and also His Resurrection, on the seventh as expressing eternal repose, and on the thirtieth in imitation of mourning of Moses by the Hebrews.

In the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal, these three Masses are votive of the third class, so they can be celebrated on fourth or third class days according to the rubrics (rubric 415). The computation of these days, however, is a bit complicated. In this regard, the 1959 edition of Matters Liturgical gives the following:

In computing the day of the Mass, one must count three or seven or thirty days exactly. This count, however, may be made either from day of death or from the day of burial; in either case the day of death or the day of burial may be either included or excluded. Consistency is not required in computing all these privileged days for the same person; thus the 3rd day may be computed from the day of burial exclusively, the 7th day from the day of burial inclusively, and the 30th day from the day of death either inclusively or exclusively. One may have these privileged Masses said on all three days or on one or two of them only; all three Masses may be said for one and the same person, not only in one church or oratory, but in more than one. It should, however, be noted that only the first 30th day is privileged. (294.d)

It is fitting that during this month dedicated the Holy Souls that the Faithful be urged, when preparing the funeral rites of a loved one, or even for oneself (if plans are being made in advance), to see if this ancient tradition of celebrating Masses for the departed on the third, seventh, and thirtieth days can be arranged as well, so that this venerable tradition may continue, and the souls for whom these Masses are offered receive the associated spiritual assistance.

Fr. Wiliam Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- See, for example, Appendix II of Neale, J. M.’s The Liturgies of the Saints (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2002) and the Old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Prayers for the Dead.”

- The translations of these orations are based on those presented in The Saint Andrew Daily Missal (St. Paul: The E. M. Lohmann Co., 1940), p. [99] and The Roman Catholic Daily Missal (Kansas City: Angelus Press, 2004), pp. 1617-1618.

- Old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Masses of Requiem.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Translated Texts for Historians, Volume 43 – Ambrose of Milan: Political Letters and Speeches. Trans. Liebeschuetz, J. H. W. G. with the assistance of Hill, Carole. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), p. 178.

November 2, 2023

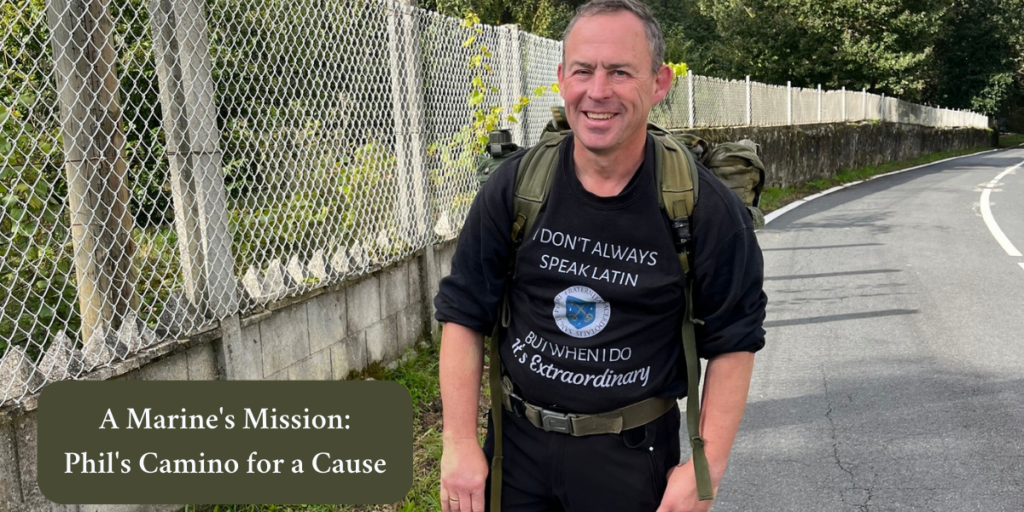

A Marine’s Mission: Phil’s Camino Pilgrimage

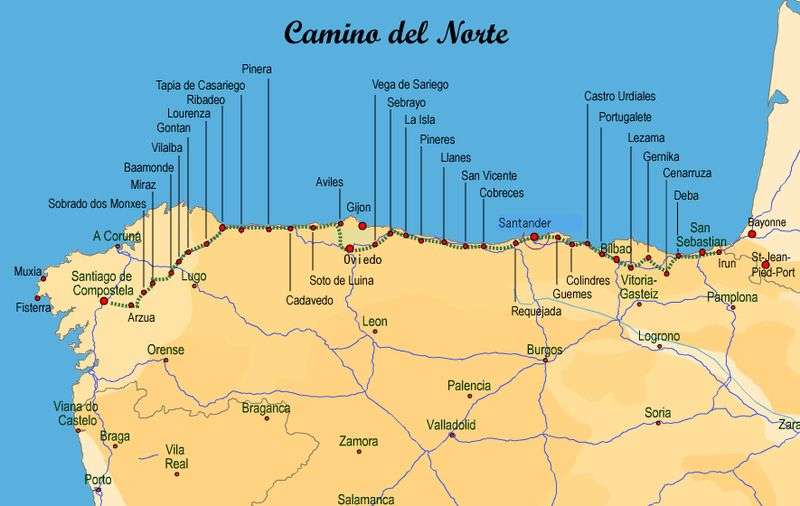

Every year, more than 400,000 pilgrims from around the world walk the Camino de Santiago—the Way of St. James—in Spain, hoping to encounter God in a new way. For U.S. Marine veteran Philip Webb, this trek is also a chance to raise money for a very worthy cause: FSSP Mission Tradition.

Webb, a retired machinist, begins his Camino pilgrimage on October 3 and plans to finish by November 10, the 248th anniversary of the U.S. Marine Corps.

“For me, the Camino walk is a fantastic opportunity to disconnect from the noise of the world,” said Webb. “It’s a chance to live each day by faith, not knowing what lies ahead on the trail. It’s also a way to draw attention to a very worthy cause. The priests of Mission Tradition do an excellent job of bringing the light of Christ to remote and often dangerous places. This draws me to their cause, and I’m happy to donate my efforts to them.”

Read more at FSSP Mission Tradition.

October 3, 2023