Praying for the Dead and the Requiem Mass

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

“It is therefore a holy and wholesome thought to pray for the dead, that they may be loosed from sins.” (2 Mac 12:46)

It is a dogma of the Catholic Church that the souls detained in Purgatory (the Church Suffering) can be assisted by the suffrages of the living faithful (the members of the Church Militant). These suffrages (intercessory prayers, indulgences, alms and other pious works, and above all the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass) remit before God some degree of the temporal punishments due to their sins which the poor souls still have to render.1 So important is the undertaking of these suffrages that the Church has listed it as part of one of the Spiritual Works of Mercy, namely, “to pray for the living and the dead.”

It is a dogma of the Catholic Church that the souls detained in Purgatory (the Church Suffering) can be assisted by the suffrages of the living faithful (the members of the Church Militant). These suffrages (intercessory prayers, indulgences, alms and other pious works, and above all the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass) remit before God some degree of the temporal punishments due to their sins which the poor souls still have to render.1 So important is the undertaking of these suffrages that the Church has listed it as part of one of the Spiritual Works of Mercy, namely, “to pray for the living and the dead.”

As the Roman Liturgy developed, certain Masses were produced whose sole purpose is to pray for the dead. When the various forms of the Masses for the Dead were settled, only the readings and the three prayers (the Collect, Secret, and Postcommunion) of these Masses differed among them. The chants and ceremonies for the different types of Masses for the Dead are the same. Among these Masses are the Funeral Mass and the three Masses assigned to All Souls’ Day. Each of these Masses for the Dead may be called a “Requiem Mass” based on the first word of the Introit (the entrance chant) which is common to all.

Sorrow is the natural response to the loss of a loved one. The Church shares in this sorrow of her children. This sorrow is deepened by the Church’s general uncertainty concerning the eternal fate of her children who have died (except, of course, those solemnly canonized). For these reasons, during a Requiem Mass, she vests her ministers in the color black, a color symbolizing the deepest mourning and grief. The yellow hue of the unbleached candles and the absence of flowers and organ add to the sorrowful atmosphere. But the Church and her children, relying on the mercy and love of God, hope that a blessed, eternal reward will be granted to the faithful departed. These two themes, of sorrow and of hope, are intermingled throughout the Requiem Mass both in the texts themselves and in the tones of the chants. For example, the chants at the start of the Mass are in a sorrowful tone, but, at the end of the ceremonies, the chant is lighter.

The sole focus of the Church during a Requiem Mass is the soul or souls for whom the Mass is being offered. This is clearly brought out in the liturgical ceremonies that are proper (although not necessarily unique) to this Mass. Many of these proper ceremonies are omissions from what is normally performed, as they would be unfitting for such a Mass or would draw the Church’s attention away from the departed. Other changes are made to direct the liturgical focus to the departed and away from those present. The following are practices proper to the Requiem Mass:

- All of the ceremonial kisses during the Mass are omitted except during vesting and divesting and those that reverence the Altar (which represents Christ).

- The Prayers at the Foot of the Altar are shortened, as the joy expressed in the excluded portion is out of place in such a Mass.

- The Altar is not incensed at the beginning of the Mass.

- At the Introit, all present would normally cross themselves, but during a Requiem, they do not. Instead, the Priest makes a Sign of the Cross over the Missal, which, for this act, represents the deceased.

- The Gloria and Alleluia, as they are joyful, are omitted. The Alleluia is replaced by a Tract.

- The Sequence Dies Iræ is recited before the Gospel.

- Unless performing an action that would require otherwise, all but the Sacred Ministers kneel during the Collect (opening prayer) and Postcommunion (prayer after communion) in supplication for the departed.

- The Subdeacon is not blessed after chanting the Epistle.

- Prior to the reading of the Gospel, a preparatory prayer is omitted and the Deacon is not blessed.

- Candles and incense are not used during the proclamation of the Gospel.

- After the proclamation of the Gospel, the Gospel Book (Evangeliarium) is not kissed and the associated prayer is omitted.

- The water in the cruet at the Offertory, which represents the people, is not blessed.

- The Gloria Patri (the Glory be), as it is an expression of joy, is omitted.

- During the Offertory, only the Oblations (the offered bread and wine), Altar, and Priest are incensed. Usually, all present would be incensed as well.

- Unless performing an action that would require otherwise, all but the Sacred Ministers kneel from the Sanctus until the reception of Communion (not even standing for the Our Father).

- During the Canon (Eucharistic Prayer), the Subdeacon does not hold the paten as the Roman Rite does not have a black humeral veil. He does, however, incense the Host and the Chalice during the Elevations.

- The endings of the Angus Dei (the Lamb of God) are changed from “have mercy on us” and “grant us peace” to “grant them rest” and “grant them eternal rest.” The striking of the breast is omitted.

- The Pax (Sign of Peace) is omitted.

- The normal dismissal, Ite, missa est, is omitted. In its place is said Requiescant in pace (may they rest in peace).

- The blessing of the faithful at the end of Mass is omitted.

- If a Bishop celebrates a Requiem, he does not use the crosier, the ceremonial shoes and stockings (buskins), or gloves. He wears only the simple white mitre during the ceremonies and puts on the maniple before the Prayers at the Foot. He does not bless any of the servers or ministers during the ceremonies.

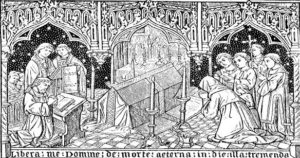

An Absolution ceremony may be performed following the Mass. This ceremony takes place at the coffin or, if the body (or bodies) is (are) not present, at a catafalque (a coffin-like structure) or at a black pall spread on the floor. The catafalque or pall represent the body (bodies) of the deceased. During the ceremony, the coffin, catafalque or pall is incensed and sprinkled with Holy Water and prayers are said on behalf of the departed.

An Absolution ceremony may be performed following the Mass. This ceremony takes place at the coffin or, if the body (or bodies) is (are) not present, at a catafalque (a coffin-like structure) or at a black pall spread on the floor. The catafalque or pall represent the body (bodies) of the deceased. During the ceremony, the coffin, catafalque or pall is incensed and sprinkled with Holy Water and prayers are said on behalf of the departed.

The previously mentioned uncertainty concerning the final state of the souls of the Church’s children who have died is, in a sense, a blessing for those who survive the departed. This is because our Faith teaches us that one can always pray for good outcomes of past events whose conclusions are hidden from mortal eyes. As God is outside of time, past, present and future have no real meaning for Him. As strange as it might seem, God can act in the past due to things which happen in the future. Therefore, prayers offered on behalf of the dead not only effect their state in Purgatory but can also have an influence at a moment of death that occurred in the past of those praying.

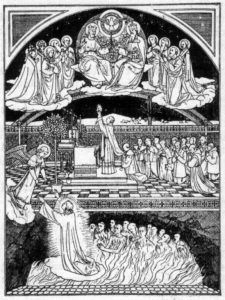

The Liturgy for the dead, based on this truth, places the Church and the faithful as pleading figures accompanying the departed soul into the presence of the Judge at the moment of death – pleading figures praying, imploring, on behalf of the soul before the unchangeable eternal sentence is pronounced. This also explains why this Liturgy asks for things that would have chronologically already been decided irrevocably (such as the welcome to heaven or condemnation to hell). While treating of the ceremonies of All Souls’ Day, Dom Guéranger explains this as follows: “to God, Who sees all times at one glance, this day’s supplication was present at the moment of the dread passage, and obtained assistance for the straitened souls.”2 It should always be remembered that death does not end relationships, but only changes them.

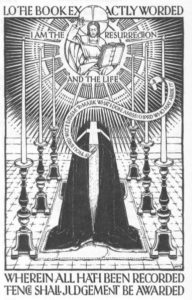

But the Church in her Liturgy is not content with simply being a pleading figure. So great is her love for her children, that the Church, and the faithful united with her, takes on, as it were, the identity of the departing soul and speaks as the soul should have spoken at the moment of passing. This explains why the first person (“I” or “me”) is used in many of the chants of the Mass and surrounding ceremonies. In these places it should be understood that the reciters are speaking on behalf of the deceased at the moment of death.3

As the faithful prepare to celebrate the Masses of the upcoming All Souls Day and to keep November as the Month Dedicated to the Poor Souls, may these reflections aid them in understanding the great work of mercy they are undertaking.

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- See the Old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Prayers for the Dead.”

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, 15 (Time After Pentecost Book VI). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), 142 (All Souls’ Day).

- See the Old Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Libera Me.”

October 25, 2022