Salvation History…on a Stick

In the Year of Our Lord 1838, Fathers François Blanchet and Modeste Demers traveled to Fort Vancouver at the behest of the bishop of Quebec. The mission entrusted to these two priests was simple on its face, but it was also impossibly vast in its scope. They were tasked to spread the message of the Gospel throughout the Pacific Northwest, in a region that stretched from California to Alaska.

The Fathers, clearly, would need help. They managed to get a few literate men to serve as catechists for the white settlers, but this approach would not serve so well with the native tribes of the area. Each tribe had its own language, and though some were closely related, others were so different from the rest that they would have to be learned from scratch. The Chinook Jargon, which served as a sort of general inter-tribal means of communication throughout the Northwest Coast, was only a simplified pidgin language useful primarily for trading scenarios, not for teaching theology.

But the missionaries began to observe how the interpreters they relied on very naturally used the native love for rhetoric and oratory to give “a new force and new weight” to Catholic doctrine—in languages that white men could only stammer in.

Blanchet and Demers thus determined that those best suited to catechize the Indians were Indians themselves. But how to transform a mere interpreter into a trained catechist, capable not only of understanding but also teaching the vagaries of doctrine?

The answer came from an old tradition ingrained in native Northwestern culture itself. Catholic teaching would be encoded the way Indians had from time immemorial recorded the history of their families and tribes: on a totem.

“In looking for a plan,” Blanchet writes, “[I] imagined that by representing on a square stick, the forty centuries before Christ by 40 marks; the 33 years of our Lord by 33 points, followed by a cross: and the 18 centuries and 39 years since by 18 marks and 39 points, would pretty well answer [my] purpose, in giving [me] a chance to show the beginning of the world, the creation, the fall of the angels, of Adam; the promise of a Savior, the time of His birth, and His death upon the cross, as well as the mission of the apostles.”

“In looking for a plan,” Blanchet writes, “[I] imagined that by representing on a square stick, the forty centuries before Christ by 40 marks; the 33 years of our Lord by 33 points, followed by a cross: and the 18 centuries and 39 years since by 18 marks and 39 points, would pretty well answer [my] purpose, in giving [me] a chance to show the beginning of the world, the creation, the fall of the angels, of Adam; the promise of a Savior, the time of His birth, and His death upon the cross, as well as the mission of the apostles.”

This miniature Catholic totem pole was called the “Sahale” stick, from the name for God in Chinook.

Abandoning theological abstraction for a straightforward historical narrative proved a masterful stroke of evangelization. Like a tribal or familial totem, the Sahale stick was a symbolic retelling of salvation history in visual terms the natives of the Northwest could readily understand.

All that remained was to put it to the test.

Blanchet had a Sahale stick carved for Tslalakum, a visiting chief of the Straits Salish. After a mere eight days of instruction Tsalakum had mastered the concepts engraved on it, and he brought it back to his native land. As word spread to other tribes, Blanchet made and gave away eight more at Nisqually in 1839.

Hand-carving the four-foot sticks, however, quickly proved too laborious for the burgeoning demand. So Blanchet and Demers switched to drawing the Sahale stick’s symbols on paper and calling these pictures “Catholic ladders.”

Then, almost a year after giving the first stick to Tslalakum, Blanchet was finally able to visit his tribal home on Whidbey Island, hoping to follow up on the chief’s visit with some basic catechesis.

Amazingly, he found a tribe already well familiar with the tenets of Christianity. Chief Tslalakum’s eight days of instruction had produced an entire tribe that not only knew the main points of the faith, but had also managed to learn some hymns as well. Tslalakum had given his first Sahale stick to another chief and made a copy for himself. And other chiefs like Witskalatche, Netlam and Sehalapan had similar resounding successes in lands where no priest had ever stepped foot.

The Sahale stick, by successfully “baptizing” an ancient native practice of the Northwest Coast, had proved both a wonderfully ingenious way to teach the faith to the Indians. And almost 200 years later, the tradition of making Sahale Sticks and Catholic Ladders still continues to this day, as part of cultural patrimony of Catholicism in the region.

June 12, 2020

The Home Altar through the Liturgical Year

Locked out of our churches for so many weeks this year, and being compelled to either offer prayers on our own, read our Missals, or follow along with televised Masses, we have all gained a new appreciation for bringing the liturgy into our homes.

The concept of the “domestic Church” has a very ancient pedigree. In his letter Of the Good of Widowhood, St. Augustine asked to be included in the prayers of the holy woman Juliana cum tota domestica vestra Ecclesia: “with all your household Church.” St. John Chrysostom called the home a micra ecclesia, a little church, and St. Clement of Alexandria called marriage a microbasileia, a little kingdom.

While naturally we can’t offer Mass or other rites as our priests and bishops do in sacred buildings, we are all still very much expected to unite ourselves with those rites in spirit, even to the extent of making our homes a spiritual and even physical extension of our parishes into the secular world.

Thus, many of us have already created a little prayer corner in our homes where we can say the Rosary, offer morning or night prayers, and light a candle once in a while.

And many households also, especially those with children, take great delight in characteristic seasonal devotions, such as constructing a Nativity scene, chalking the lintels at Epiphany, and setting up an Easter candle or garden.

Unfortunately, these seasonal devotions by their very nature tend to come and go, leaving large sections of the year with few obvious customs to replace them.

We are very soon to enter the long period of the Sundays after Pentecost—half a year of “ordinary” green Sundays. How can we keep ourselves and our children as engaged as we seem to be on the 1st Sunday of Advent?

Here is where a home altar can come in.

By maintaining a home altar not just as a static home for our rosaries and prayer books but as a closer mimic of its ecclesial namesake, the liturgical year can be a visible part of your home at all times.

There are many possible methods to do this, but here is one framework.

First, an altar cloth of the appropriate liturgical color can be used. A fabric store will be happy to cut bolts of inexpensive colored cloth to your specifications, and these can then be hemmed and decorated with embroidery or appliqué. (Or, if you are not so skilled in the domestic arts, a wide strip of white lace is an attractive complement.) The altar cloth is changed at the beginning of each new liturgical season and, if desired, at important feast days such as the Assumption.

Next, statues and icons of favorite family saints are placed atop the altar. Some may stay there year round—favorite images of Our Lord and Our Lady for example—but the others can be rotated in at the beginning of each month, depending on the sanctoral calendar. So on March 1st, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Gregory the Great, St. Patrick, St. Joseph, and the Annunciation appear on the altar, to be replaced on April 1st by St. George, St. Mark, St. Catherine of Siena, and St. Kateri (in Canada). And as each saint’s feast day arrives, the appropriate image can be moved to the center of the altar and a votive candle set before it.

Natural decorations such as flowers and greenery can be changed at the Ember Days or Quartertides. Advent is a wonderful time for evergreens and wreaths. At the Lenten Embertide, we content ourselves with dry sticks and thorns, then palms or pussy willows during Holy Week, until Easter morning when the altar joyously breaks forth in flowers. After the Ember Days of Pentecost, the flowers can be continued along with typical summertime greenery, until the Ember Days of September, when autumnal displays and harvest decorations close out the liturgical year.

Other pious practices, borrowed from our parishes, quickly suggest themselves. Some extra violet cloth will allow you to cover the sacred images at Passiontide. The home altar can be stripped on Maundy Thursday and, save for any Good Friday devotions, left bare until Easter. At All Saints’ Day, the altar can be filled to capacity with every icon and statue available. During All Souls’ Day, black cloth and family photos can remind us to pray for the Church Suffering.

Candles are an excellent addition when the children are old enough. If tapered ones are too expensive, tea lights can be used. Moreover, colored candles or votive holders can bring in secondary hues based on the season or feast. For example, a plain white altar cloth can be complemented with red and green candles for Christmas, gold or yellow for Easter, and blue for feasts of Our Lady.

Since it is a well-established liturgical principle that the Roman calendar changes according to local interest and patronage, consider how this idea can be applied to your own “little church.” Do you have special family patrons? Honor them in a special way with an octave—a week-long celebration on the family altar. Octaves used to be quite plentiful in the Roman Rite, and it is a very natural sentiment to want to extend major feasts for a week-long celebration. You can also specially celebrate family name days, baptismal and wedding anniversaries, and even those servants of God and Venerables whom you are devoted to but are not yet permitted to have a public cultus; and of course it is also a good thing to remember your loved ones on the days of their death.

Overall, maintaining a home altar provides us with a tangible and visible connection to our parishes, and it extends liturgical living well beyond the hour and a half on Sunday when we are present at Mass. We can even accompany our altar decorations with appropriate seasonal prayers—the Commemorations mentioned in our Monday article are very well suited for this purpose.

The home altar is a particularly powerful teaching tool for young children. They may not yet have the understanding or the attention span to pick up on subtle changes in recited prayers—but they are naturally fascinated by colors, images, flowers and lights and will participate with enthusiasm. (They can even be encouraged to keep “side altars” in their own rooms with colored cloths, toy saints, and their favorite medals and rosaries.)

As we finally start to emerge from our various states of lockdown, may it please God that we never have to endure such a long disruption of our parish liturgical life again.

But it was not time wasted if, having accepted the deprivation prayerfully and penitentially, we now appreciate the sacred liturgy much more keenly than we ever have before, and bring it to the very center of our homes and our hearts.

June 10, 2020

The Commemoration: A Liturgical Devotion

Blessed Be God, a prayer book which has been in print for almost a hundred years now, has enjoyed a renewed popularity of late thanks to its excellent collection of prayers and devotions.

One of the particularly wonderful things about this book is its copious use of liturgical commemorations. Commemorations are short little snapshots of a feast, traditionally used at Lauds and Vespers when that feast has been superseded by a higher-ranking one but is still nevertheless worthy of being remembered. They have three main parts: an Antiphon, a Verse and Response, and the Prayer or Collect.

Commemorations have been printed devotionally for quite some time, but few prayer books have done so as richly as this one. This one little volume can actually serve all by itself as a sort of “Little Office” for the laity that can be used throughout the year.

For Catholics, of course, the most important way to mark time is through the liturgical year. In the section “Devotions for the Holy Days and Special Feasts” (p. 196-252), Blessed Be God gives us commemorations for the Circumcision, the Epiphany, Candlemas, and St. Joseph; Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday; then ones for Paschaltide including Easter, the Rogation Days, the Ascension, and Pentecost; and finally Corpus Christi, Ss. Peter and Paul, the Assumption, Ember Days, All Saints, All Souls, Immaculate Conception, and Christmas. The following section, “Devotions for the Seasons of the Year” (p. 253-256), has additional commemorations for Advent, Christmastide, Septuagesima and Lent, Passiontide, and Eastertide.

But the book also diverges from the liturgical calendar proper and offers commemorations for each day of the week: Sunday (The Most Blessed Trinity), Monday (The Souls in Purgatory), Tuesday (The Holy Angels), Wednesday (St. Joseph), Thursday (The Most Blessed Sacrament), Friday (The Passion of Christ), and Saturday (The Blessed Virgin). Next the months are commemorated: the Holy Name in January, the Holy Family in February. St. Joseph in March, and so on.

Catholics may well know that May is dedicated to our Lady, that October is dedicated to the Rosary, and November is for the Holy Souls. We abstain from meat, of course, on Fridays. But what do we do on the other months and days? Are they not worthy of giving back to God as well?

And even the well-known “special” days and month just mentioned–do we really acknowledge and keep these devotionally? Or do we sometimes simply acknowledge the fact and move on, as if the knowledge alone was sufficient?

The great strength of Blessed Be God, with its numerous commemorations, is that it helps give structure to those popular devotions. Each feast, each season, each day of the week, and each month of the year has its own special prayer. These take less than a minute to say, and as such they are accessible even to the busiest working dad and homeschooling mom.

Praying the commemorations keeps us in the spirit of each liturgical feast and season, and since they come directly from the texts of Lauds and Vespers, by entering more deeply into them we can, in our own little way, participate in the public liturgy of Holy Mother Church.

June 8, 2020

The Latin Mass Among Millennials & Gen Z: A National Study

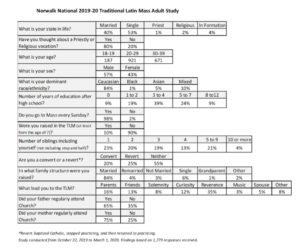

A recent online survey of 1779 adults from 39 states found that the “Traditional Latin Mass is experiencing a high volume of participation and interest in the 18-39 demographic.”

Fr. Donald Kloster of the diocese of Bridgeport, CT, with the help of other contributors, conducted the survey between October 22, 2019 and March 1, 2020.

Fr. Kloster directed his study not at a general Catholic audience but at those within the age range who at least prefer the Latin Mass. And his findings are remarkable. The survey showed an astounding 98% weekly Mass attendance in the 18-39 age group . These adults would have been born roughly in the range of 1980-2001, and therefore largely represent the Millennial generation (1981-1996) and the earliest individuals in Gen Z (1996-2010).

How does that compare to statistics in the church at large? Research done by Gallup shows dramatic declines in church attendance since 1955 in all age categories: with the 21-29 age group consistently at the bottom, at 25% weekly Mass attendance. The Gallup data shows a steep drop from 73% attendance in 1955 to percentages in the mid-30s by 1975. This drop began with the members of the Silent generation (born 1928-1945) and the early Baby Boomer generation (1946-1955). After holding steady for a decade, it dropped to a low point with Generation X (1964-1979), where it has largely remained for the Millennials.

Although a large majority of the respondents said that their parents regularly attended Church, only 10% of those surveyed were raised in Traditional Latin Mass households, and only 16% reported that their parents had led them to the ancient liturgy.

The reasons that did lead them to Mass, ranked in descending order, are as follows:

The reasons that did lead them to Mass, ranked in descending order, are as follows:

35% Reverence

16% Parents

13% Friends

12% Curiosity

8% Solemnity

8% Other

5% Spouse

3% Music

Combining some of this data, we can see that personal preferences (reverence, curiosity, solemnity, and music) account for 58% of the total, while peer influences (friends, spouses) account for 18% of the total. Thus, to the tune of 76%, the impetus to attend the Latin Mass among 18- to 39-year-olds seems to be largely coming internally from within their own generation, rather than being inherited from previous generations.

One important factor in the study seems to be a strong religious family life: 65% of the respondents’ fathers regularly attended Church, 75% of their mothers regularly attended Church, and fully 84% were raised in a married (but not remarried) household. And note that these fathers and mothers are the Baby Boomers and Gen Xers whose generations saw the steep decline in Mass attendance mentioned earlier.

It seems that those Boomers and Xers in the parent generations who retained a solid family structure and regularly attended Mass—whether or not they themselves attended a Latin Mass—helped set the stage for the Millennials and early Gen Z to rediscover tradition through personal and peer channels. Of course we cannot discount intellectual influence from older traditionalists online or elsewhere, but the trope of “cultish” parental influence is not borne out at all in this data. Fr. Kloster’s study suggests that these generations have come to the Latin Mass largely on their own and for their own reasons.

Fully 80% of Fr. Kloster’s respondents had thought of a priestly or religious vocation. This finding will come as little surprise to those in Latin Mass communities that, while often small, tend to generate vocations well beyond the norm. Moreover, men comprised 57% of those responding to the survey, while only being 49% of the population. All of these numbers are highly relevant to the priest shortage, and suggest a clear way out of it.

And as far as the laity goes, if the trend of 98% Mass attendance continues to hold across the wider Catholic world, it hints not just at potential to reverse the decline in attendance since Vatican II but to go even further and surpass the 1955 numbers of 73%-77% attendance across all age groups.

Fr. Kloster shared his thoughts with the Missive about that possibility. He theorizes that, in a few key respects, the Latin Mass today is unlike the Latin Mass of the 1950s. Priests are now saying the Mass slower, and they are offering more high Masses and solemn Masses. That more reverential approach seems to be bearing fruit.

“We are doing what the Vatican Council was supposed to do,” he said. “We are fixing all the gaps that should have been fixed.”

Overall, the findings are very encouraging, and this study will be worth continuing to unpack in the coming months and years. Kudos to Fr. Kloster and his team for taking the time to put data and actual numbers behind the anecdotal evidence that has been bandied about for a while.

A previous version of this article gave an incorrect number for the study population. -ed.

June 5, 2020

The Sacred Heart and the Strawberry

The liturgical year is a story of many layers, and one of those layers is closely tied to the natural world.

So, for instance, on the Ember Days–and those of summer begin today, as a matter of fact–the Latin Church specially marks the four seasons. Our Christmas hymns are filled with the piercing cold of winter, Easter with the blossoming of Spring, the time after Pentecost with the green growth of summer, and the apocalyptic Last Sundays of the liturgical year with the Autumn harvest.

So closely tied, in fact, is our ecclesiastical calendar to the natural cycles of the European continent that we hardly give it much thought. And since many of our churches here on the other side of the Northern Hemisphere have a similar climate and natural fauna, we can fully appreciate the Roman liturgical calendar just as it evolved across the Atlantic.

But our particular cultural and geographical environment can also offer us a new take on the Latin calendar that would not have necessarily been apparent in Europe.

A classic example is seen in this month of June: the month of the Sacred Heart.

June also marks the appearance of that very familiar fruit: the strawberry, which originally was bred from two wild varieties of the New World.

The American Indians were familiar with the original woodland strawberry, Fragaria virginiana. But their name for it did not match up with our modern English name–which refers, some think, to the straw that was used to mulch the fruit in England, or to the way it was strewn on the ground.

The American Indians were familiar with the original woodland strawberry, Fragaria virginiana. But their name for it did not match up with our modern English name–which refers, some think, to the straw that was used to mulch the fruit in England, or to the way it was strewn on the ground.

Instead, the tribes of the Eastern Woodlands called attention to what its shape and vivid red color immediately suggested. The Lenape called it wtehim–literally, “heart berry”. The Iroquois celebrated its arrival in June with a great national festival of thanksgiving, as the first berry to appear and the fulfillment of the promise of the Creator. They gave it many names such as the “the Great Medicine”, and ascribed wonderful qualities to it.

Here the natural world prefigured the supernatural…and the ancient cultures found their fulfillment in Holy Mother Church.

The Catholic Iroquois near Montreal–said by the early missionaries to have surpassed even the French Canadians in piety–largely preserved their culture intact except for “only that which vice had spoiled” in the pagan towns. These traditional concepts would have filled their minds as they gathered to hear the Introit of Holy Mass Iesos Raweriasatokenti, literally “Jesus-his-sacred-heart” right around the time when they were celebrating the strawberry’s arrival as they had done from time immemorial.

The Catholic Iroquois near Montreal–said by the early missionaries to have surpassed even the French Canadians in piety–largely preserved their culture intact except for “only that which vice had spoiled” in the pagan towns. These traditional concepts would have filled their minds as they gathered to hear the Introit of Holy Mass Iesos Raweriasatokenti, literally “Jesus-his-sacred-heart” right around the time when they were celebrating the strawberry’s arrival as they had done from time immemorial.

And we, whose ancestors have may have come to this continent from Europe, Africa, or Asia, can still hear their echoes in our own humble little gardens. With them we join in celebrating this month, not only the beginning of summer marked by these Ember Days of Pentecost, and not only the first fruits which Almighty God has provided us for our sustenance, but also the higher reality that they and the liturgy point us toward: the burning furnace of charity in the Sacred Heart of Our Savior.

June 3, 2020

Readers Reply: What Do You Miss Most Since the Lockdown?

“What do you miss most about your FSSP parishes and priests since the lockdown?”

We asked this question a few weeks ago on our Facebook page and received many thoughtful and wonderful replies–too many to reprint here. Here is a sample of what FSSP parishioners replied from across the District.

“I miss being around the holiness of our FSSP parish priests. I know this sounds crazy, but there’s a beautiful supernatural presence around priests. There’s a holy and loving, yet terrifying majesty (like the presence of Christ) that surrounds the priests.” – Eve Barbieri

“The Eucharist, high mass, Adoration, choir, incense, processions, our priests, our community. Everything.” – Anastacia Schiele

“Missing all of it, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the inspirational homilies, Confession, receiving the Body of Christ, the bells and smells, the sacred music, the rosary before mass, the interior joy in my heart knowing I was in heaven on earth, sensing the presence of Angels and saints. Oh, how does one pick from such wonders. I can’t.” – Gerianne Storelli

“I missed being physically present and the ability to physically receive Our Lord, but I am eternally grateful for the FSSP priests continuing to say the Mass daily and knowing that, even if I can’t watch online, the Mass is still prayed with reverence and devotion. I know I’m not needed for this magnificent prayer to ascend to God for all of us. I missed the Sacraments and the music and seeing my fellow Catholics after Mass. It’s returning slowly here, but who knows what will happen next? I will never take it for granted again.” – Ellen Maschino Wrinn

“I miss the profound reverence of the priests in every deliberate move they make during the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, that brings me to the realization that Jesus IS truly present on that altar. When one can come to that realization that Jesus is truly there, nothing else matters. It’s like you can be there, but not there; in the world but not in it. I long for public Masses to resume again. It’s like having a taste of Heaven, then having to go through withdrawals when it’s been taken away.” – Janet Jordan

“Mass. Our parish community. Our wonderful FSSP priests at St Mary’s. Their teachings and the many things going on in our parish. Essentially everything. At the same time, I am very thankful for all that our FSSP priests have done for us every day during lockdown. I’ve learned so much from their catechism classes and Bible studies. It has been such a huge gift and blessing.” – Jennifer Elizabeth

“Besides the Mass, I miss the more routine opportunity to go to confession on Sundays before Mass. I miss the magnificent sermons, although we can watch them online, the surrounding distractions will always put a bit of a damper on the overall impact of the sermons. I also miss our high Masses on special feast days such as St. Joseph in March and other lovely festivities outside of Sunday during the week. I greatly missed the Easter Vigil which I ardently enjoy.” – Martin Palihnich

“Community. Shared sense of vision. Besides the exquisite Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, I miss being surrounded by the faithful and their witness. I also miss the quiet and inspiring catechism of traditional church artwork in stained glass.” –Allison Girone

“What I miss most is being surrounded by the body of Christ celebrating together with the Holy Eucharist, the source and summit of our life. Seeing our priests in Persona Christi – the holy and sacred witness – offers a source of peace, comfort and strength in a world gone mad.” – Cindy Lou Teller

“The beauty, awe and reverence of the Latin Mass and the great dignity and faithfulness of the FSSP who offer it.” – Joann Veara Castricum

“Receiving our Lord. The beautiful and reverent liturgy. Confession always available. The faithful families and priests.” – Chelsea Elyse

“The whole parish standing to sing the Credo. Little people crying out in the back of the church. Candles, incense. The sensibility that we get to step into a great moment in history and join it.” – Silvia Dipippo Aldredge

“I miss my spiritual director, but I got one chance to see him at confession. He responds to the confession hotline and is always ready to step out of the rectory for a confession in the parking lot. Also love seeing him on YouTube now.” – Joe Johnson

Thank you to all who participated! To share your thoughts with fellow FSSP parishioners across North America and join in the discussion of our Missive articles, like and follow our Facebook page.

June 1, 2020

FSSP Priestly and Diaconal Ordinations 2020

Priestly and Diaconal Ordinations for the FSSP North American District will take place at the Cathedral of the Risen Christ in Lincoln, Nebraska on Monday, June 1.

Priestly and Diaconal Ordinations for the FSSP North American District will take place at the Cathedral of the Risen Christ in Lincoln, Nebraska on Monday, June 1.

Please unite with us in prayer by joining in singing or reciting the Veni Creator Spiritus for the men being ordained to the priesthood for the District:

- Rev. Mr. Daniel Alloy, FSSP

- Rev. Mr. Eric Krager, FSSP

- Rev. Mr. Joseph Loftus, FSSP

- Rev. Mr. David McWhirter, FSSP

- Rev. Mr. Javier Ruiz Velasco Aguilar, FSSP

as well as for those being ordained to the diaconate:

- Mr. John Audino

- Mr. Joseph Dalimata

- Mr. James Eichman

- Mr. Nicholas Eichman

- Mr. Joel Pinto Rodriguez

- Mr. Thu Truong

Our apostolate LiveMass.net will be live-streaming the ceremony on June 1st, from 10 AM – 3 PM Central Time.

Veni, Creator Spiritus,

mentes tuorum visita,

imple superna gratia

quae tu creasti pectora.

May 29, 2020

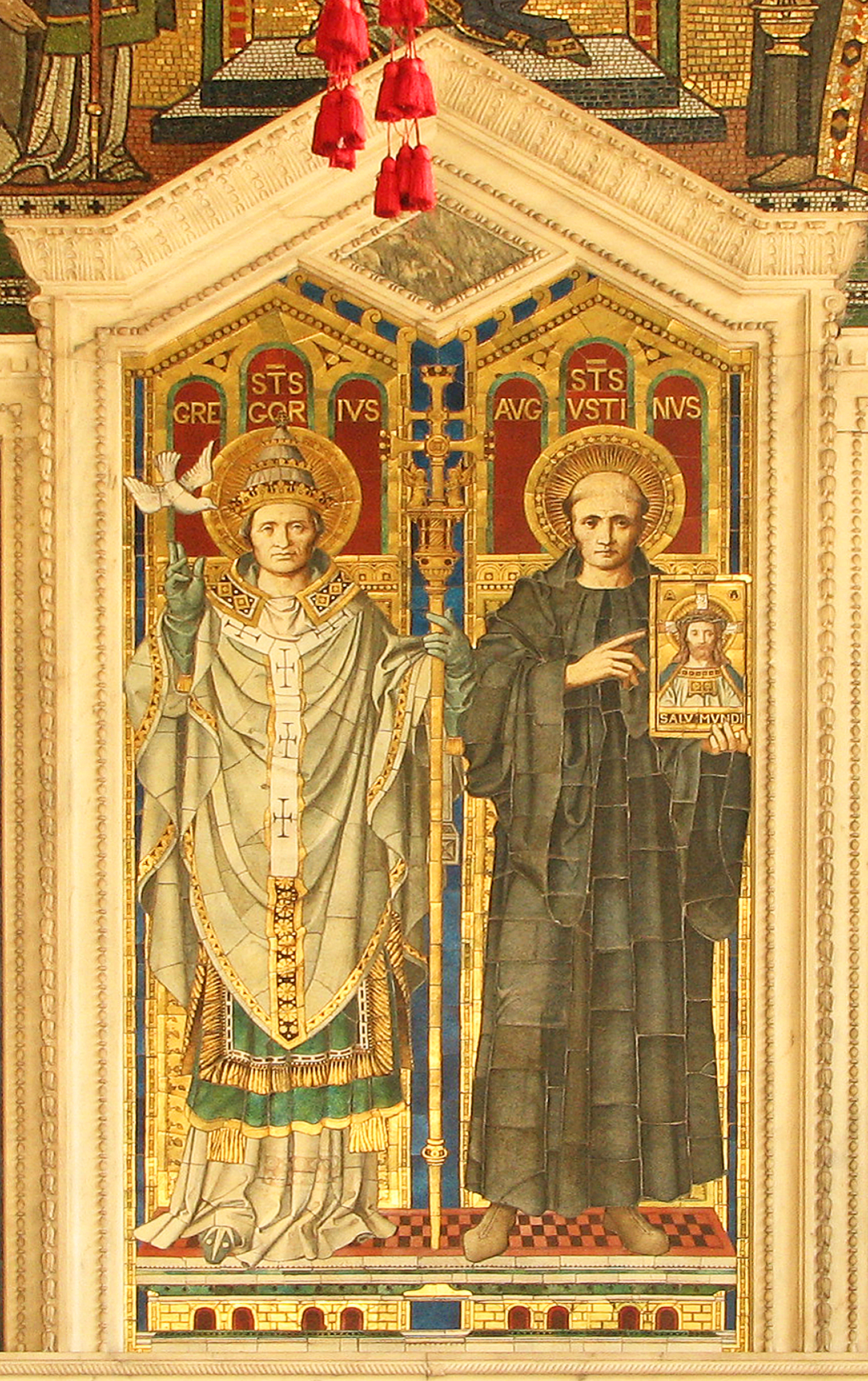

Bede, Augustine, and Gregory on 21st Century Liturgy

This week we celebrate back-to-back feasts of two great English saints–Bede the Venerable on May 27 and Augustine of Canterbury on May 28. Both of these men are recognized today as key figures in the early English Church–St. Bede who wrote the Ecclesiastical History of the English People and saved much history from oblivion, and St. Augustine who was appointed by Pope St. Gregory the Great to convert the Anglo-Saxons and become the Apostle to England.

Among many other treasures, Bede’s chronicle preserves an invaluable exchange between Augustine and Gregory. Augustine asks why communities who shared the same faith nevertheless had different liturgical expressions.

You know, my brother, the custom of the Roman church in which you remember you were bred up. But it pleases me, that if you have found anything, either in the Roman, or the Gallican, or any other church, which may be more acceptable to Almighty God, you carefully make choice of the same, and sedulously teach the church of the English, which as yet is new in the faith, whatsoever you can gather from the several churches. For things are not to be loved for the sake of places, but places for the sake of good things. Choose, therefore, from every church those things that are pious, religious, and upright, and when you have, as it were, made them up into one body, let the minds of the English be accustomed thereto.

Fourteen hundred years later, we are still coming to terms with similar issues.

The 1962 Missal has been the standard missal for FSSP parishes for so long–but many have long lamented that it is profoundly untraditional for a calendar to be “frozen in amber” without any new saints being added. For example, it feels quite unnatural to honor St. Pio of Pietrelcina everywhere but on our altars. Yet on the other hand, how would it be possible to add in 60 years of new saints while also respecting the integrity of the traditional calendar? It took until this very year to painstakingly work out a solution, through the Congregation of the Faith’s promulgation of the decree Cum Sanctissima.

Other scholars have looked back to earlier times and wondered whether it would not be truer to the classical Roman Rite to restore practices that were abolished by Pius XII’s liturgical changes of 1955. Rome has granted some limited allowances along these lines as well, with some FSSP parishes being provisionally allowed to use the pre-1955 Holy Week rites.

Like Augustine on his arrival on the British Isles, we find ourselves confronted with disparate liturgical books but a wish to harmonize them in a single “body” that best exemplifies the overall spirit of the classical Roman Mass. Our different missals are chronological rather than geographical, but the essential problem is the same.

A liturgical purist might well object that to foray outside the protective confines of the 1962 missal is, to use the vernacular expression, “picking and choosing.” That for something as vitally important as the liturgical books of the Roman Rite, we should simply stick to the commonly-used missal and be done, instead of embarking on a complicated synthesis that will lead (so the thinking goes) to inevitable liturgical chaos.

But thanks to the pens of both Augustine and Bede, we can put the question back to Pope St. Gregory for advice.

Gregory flatly stated that it pleased him for Augustine to “carefully make choice” from the liturgical practices of different churches. Indeed, he himself was responsible for finalizing the Traditional Latin Mass as we know it today.

However, he is no reckless reformer. He naturally assumes that such a synthesis will only make use of those things that “may be more acceptable to Almighty God”, and are “pious, religious, and upright”. In other words, the ingredients of that synthesis must be chosen from what is in accord with the faith that Christ has given us and that contributes most to God’s glory. This principle necessarily excludes from consideration any concept that stems from mere convenience, worldliness, current fashions, or hostility or embarrassment toward tradition.

As the spiritual descendants of the English Church founded by Augustine and chronicled by Bede, we ought to consider how to apply Gregory’s sage words to our own time and our own liturgical challenges. Granted, they do not give us minute instructions to that effect, but they do provide us with some key points to keep in mind.

For tradition, in its fullest and truest definition, is not so much the exclusive property of one Missal or another, but remains ever present, in varying degrees, as a unifying thread through all of them. May Sts. Bede, Augustine, and Gregory watch over us as we strive to preserve it.

May 27, 2020

A Prayer for the Unknown Soldier

by Rachel Shrader

A blessed and peaceful Memorial Day to all. Although today evokes thoughts of barbecues, get-togethers with family and friends, and the unofficial beginning of summer, much of what we would normally have planned for today may have been curtailed by recent events and the accompanying closures. But perhaps such restrictions give us a chance to pause and reflect on what this day is really about, and the relative isolation we may have to endure may be a fitting reminder of those who are no longer with us, and whose absence will remain even when the lockdowns are lifted.

Memorial Day is, of course, a tribute to those who have given their lives in the service of our country. Though different wars happen for different reasons in different eras with varying levels of popular support, what is common to them all is that many went, many returned, and some did not. All who went raised their right hand and swore an oath to support and defend the Constitution, with the implicit obligation to give their lives in its defense if necessary, and some fulfilled their oath to the letter. Some military children have rejoiced at their parents’ return from war; some have wept. Some parents have greeted their returning sons and daughters with laughter and “Welcome Home” signs; others have greeted flag-draped coffins with a sorrow that, unless experienced, is hard to comprehend. For some, remembering those who have made the ultimate sacrifice is something they do every hour of every day.

A couple years ago I visited Arlington National Cemetery with a friend. We both have relatives buried there. It was a drizzly day, the dreary weather and the thousands of identical gravestones cast across the green hills a somber reminder of the sacrifices of so many. We stopped at one of the most famous graves in the cemetery, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a monument to those unidentified dead and missing of the World Wars, Korea, Vietnam, and by extension all conflicts in which the U.S. has been involved. The U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Regiment maintains a constant presence there, guarding the Tomb day and night, every day of the year, and we watched the impressive changing of the guard that occurs every 30 or 60 minutes depending on the time of year. It is fascinating to me that the most carefully guarded and iconic of all graves in Arlington belongs to those who do not have so much as an identity, who are, in a sense, the least among the thousands of their brethren buried there, the least loved, the least known.

But in God’s view, not one is forgotten. Not even a sparrow falls to the ground without His knowledge (Matthew 10:29), and He knows the names of all the unknowns who lay buried in Arlington, in the fields of France, in the depths of the sea, or elsewhere in unmarked graves. He is a God well-acquainted with both obscurity and sacrifice, Who chose to live in obscurity most of His earthly life and allowed Himself to be counted with the transgressors in His death. He is the God Who told us that “greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13), the day before He gave us the most perfect example of sacrificial love when He died on the Cross.

Indeed, something about obscurity speaks deeply to the nature of sacrifice. A sacrifice is magnified when the giver gains no glory from it, in life or death, so the unnamed soldier stands as an example of a particularly high ideal of self-sacrifice. None of them chose to be unknown, but nonetheless, they and their known compatriots illustrated for us, when they took the road from which they would not return, the idea that some things are worth the sacrifice of our own life, our own future, and sometimes, our own name.

So let us remember today all who have made the ultimate sacrifice, especially, perhaps, those who are unknown. Not all of us can raise up physical monuments, but we can send up a prayer for the unknown soldier, that, in a busy and forgetful world, every one may be prayed for, thanked, and remembered. +

Réquiem ætérnam dona eis, Dómine: et lux perpétua lúceat eis. Requiéscant in pace. Amen.

Rachel Shrader was the editor and primary writer of the Missive from its inception in June 2017 until May 2020. She now contributes as a freelance writer, covering military topics, the international work of the FSSP, and FSSP parish life.

May 25, 2020

The Lady in Blue: Mystical Missionary of Texas

In the summer of 1629, about 50 Jumano Indians from western Texas appeared before the Spanish Franciscan friars at the town of Isleta, near modern-day Albuquerque, NM.

Smaller groups of the Jumano had been coming there for some years, each time asking for missionaries to teach their as-yet-uncatechized nation the faith of Christ. The friars inquired exactly how they had learned about Our Lord, and in return they would always tell the same rather odd story: that a mysterious “Lady in Blue” had been appearing among them and instructing them about God and the Christian religion. It was she, they said, who told them to come to this place and ask for Baptism.

Although the friars were sympathetic to the Jumanos’ need for missionaries, the tale about the Lady had been easily enough dismissed: there were no Spanish friars in that faraway region, let alone women.

But on this last embassy in 1629, that odd story struck a chord with their superior Fr. Alonso de Benavides, who had been charged to investigate these strange reports–and also to get to the bottom of strange rumors that a Spanish nun was somehow being mystically transported to the Americas. He interviewed the Jumano themselves, who pointed to a portrait of a nun and stated that the Lady in Blue, though younger in age, wore similar clothes.

Intrigued, he sent two missionaries to the Jumano homeland in western Texas. The missionaries found the people knowledgeable of the faith, and baptized a number of them. Benavides composed an account of what happened, then set off for Spain, trying to track down who the nun was. There he learned that it was Sister Maria of the convent of the Immaculate Conception in Agreda. Under obedience, she was directed to reveal these hidden aspects of her interior life, and she also described details of the country and the different peoples of the region. Benavides left the meeting completely convinced. Later, the ecclesiastical authorities investigated her and found her mystical gifts to be authentic.

Intrigued, he sent two missionaries to the Jumano homeland in western Texas. The missionaries found the people knowledgeable of the faith, and baptized a number of them. Benavides composed an account of what happened, then set off for Spain, trying to track down who the nun was. There he learned that it was Sister Maria of the convent of the Immaculate Conception in Agreda. Under obedience, she was directed to reveal these hidden aspects of her interior life, and she also described details of the country and the different peoples of the region. Benavides left the meeting completely convinced. Later, the ecclesiastical authorities investigated her and found her mystical gifts to be authentic.

To this day, American folklore reveres Venerable Mary of Jesus of Agreda as one of the founders of the Catholic faith in the state of Texas–despite her apparently never leaving her convent. But it is through her spiritual writing that she earned the most fame in her lifetime. Indeed, Benavides himself would later say that “I call God to witness that my esteem for her holiness has been increased more by the noble qualities which I discern in her than by all the miracles which she has wrought in America.”

Venerable Maria de Agreda–her cause for beatification is now ongoing–left her mortal life on May 24th, 1665, leaving behind a spiritual classic: the Mystical City of God.

And the locals continue to cherish a legend that when she said farewell to the Indians for the last time and faded away beyond the hills, she left the area blanketed in deep blue flowers the color of her robe–the Texas bluebonnet.

May 22, 2020