The Times of Mass

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

“What time is Mass?” is a question heard frequently enough in Catholic households. Such a question is reasonable as each parish will have its own Mass schedule, taking into consideration the work schedule of the parishioners, the local traffic conditions at different times of the day, and other such factors. There seems to be no set time for Mass to be celebrated, and some surprise is even experienced when “At midnight,” is answered to the question “What time is the Christmas Midnight Mass?”

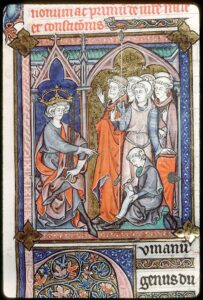

Previously, however, the situation, particularly that of the ancient Papal Station Masses1 and of the conventual (i.e. the community) Masses of monastic communities, was different. Here, depending on what the day was on the Church’s liturgical calendar, the Mass would occur at different times of the day. St. Thomas Aquinas captured this ancient tradition in his Summa Theologica. But, in order to understand what he wrote, one must understand how the ancient Romans would have kept time. For the ancient Roman, there would be 12 hours of daylight, regardless of how much daylight there might be on a given day. As a result, an “hour” would vary in length depending on how much daylight a given day would have. Based on this system, the Third Hour (Terce) marked when the sun was halfway up to its zenith, the Sixth Hour (Sext) marked when the sun reached its zenith, and the Ninth Hour (None) marked when the sun was halfway down from its zenith. In some explanations, the Third Hour is associated with our 9 am, the Sixth Hour with 12 noon, and the Ninth Hour with 3 pm, but these are approximations. The names of these Hours were adopted as the names of portions of the daily cycle of prayers of the Divine Office which are associated with each particular time of day.2 With this explanation, St. Thomas’s text can be presented (S.T. III, q. 83, a. 2, ad. 3).

As already observed (III:73:5), Christ wished to give this Sacrament [the Eucharist] last of all, in order that it might make a deeper impression on the hearts of the disciples; and therefore it was after supper, at the close of day, that He consecrated this Sacrament and gave it to His disciples. But we celebrate [Mass] at the hour when our Lord suffered, i.e. either, as on feast-days, at the hour of Terce, when He was crucified by the tongues of the Jews (Mark 15:25), and when the Holy Ghost descended upon the disciples (Acts 2:15); or, as when no feast is kept, at the hour of Sext, when He was crucified at the hands of the soldiers (John 19:14), or, as on fasting days, at None, when crying out with a loud voice He gave up the ghost (Matthew 27:46-50).

Nevertheless the Mass can be postponed, especially when Holy Orders have to be conferred, and still more on Holy Saturday; both on account of the length of the office, and also because Orders belong to the Sunday, as is set forth in the Decretals (dist. 75).

Masses, however, can be celebrated “in the first part of the day,” owing to any necessity; as is stated De Consecr., dist. 1.

The same tradition is expressed by William Durandus the Elder, Bishop of Mende (d. A.D. 1296), the great medieval liturgical commentator, in his Rationale Divinorum Officium (see IV, I, 20-21). He also adds that:

However, on the day of the Lord’s Nativity a Mass is sung at night, as already noted under that feast. And then if two Offices occur on the same day during Lent – which we call “double days” – the Mass for the feast is said at the third hour, without genuflection, and the daily office for Lent at the ninth hour, with genuflection. During the season of Advent, the Mass for a Saint’s feast is celebrated at the third hour.3

This practice of having more than one Mass per day is also noted by St. Thomas: “Likewise on other days upon which many of God’s benefits have to be recalled or besought, several Masses are celebrated on one day, as for instance, one for the feast, and another for a fast or for the dead” (S.T. III, q. 83, a. 2, ad. 2).

On feast days, Mass would be said mid-morning, and, on non-feast, non-fasting days, Mass would be said around noon. On fasting days, Mass would be said midafternoon, after which the Romans would break their fast, which at the time meant no eating at all before this point.4 Yet regardless of the time Mass was celebrated, a connection was made with Our Lord’s suffering and death. Time is sacred and sanctified. Not just days and seasons, but even the different hours of the day.

St. Thomas, in the above, noted that on Ember Saturdays and on Holy Saturday,5 when ordinations would have historically been conducted, the Liturgy could be postponed from None because Holy Orders belong to Sunday. As an authority for this position, he referenced the Decretals of Gratian, the contemporary collection of Canon Law. The entry referenced by St. Thomas in the Decretals is itself a portion of the Letter of Pope St. Leo the Great (reigned A.D. 440-61) to Dioscorus, Bishop of Alexandria. The pertinent part of the Letter is given here:

That therefore which we know to have been very carefully observed by our fathers, we wish kept by you also, viz. that the ordination of priests or deacons should not be performed at random on any day: but after Saturday, the commencement of that night which precedes the dawn of the first day of the week should be chosen on which the sacred benediction should be bestowed on those who are to be consecrated, ordainer and ordained alike fasting. This observance will not be violated, if actually on the morning of the Lord’s day it be celebrated without breaking the Saturday fast: for the beginning of the preceding night forms part of that period, and undoubtedly belongs to the day of resurrection as is clearly laid down with regard to the feast of Easter. For besides the weight of custom which we know rests upon the Apostles’ teaching, Holy Writ also makes this clear, because when the Apostles sent Paul and Barnabas at the bidding of the Holy Ghost to preach the gospel to the nations, they laid hands on them fasting and praying: that we may know with what devoutness both giver and receiver must be on their guard lest so blessed a sacrament should seem to be carelessly performed. And therefore you will piously and laudably follow Apostolic precedents if you yourself also maintain this form of ordaining priests throughout the churches over which the Lord has called you to preside: viz. that those who are to be consecrated should never receive the blessing except on the day of the Lord’s resurrection, which is commonly held to begin on the evening of Saturday, and which has been so often hallowed in the mysterious dispensations of God that all the more notable institutions of the Lord were accomplished on that high day. On it the world took its beginning. On it through the resurrection of Christ death received its destruction, and life its commencement. On it the apostles take from the Lord’s hands the trumpet of the gospel which is to be preached to all nations, and receive the sacrament of regeneration which they are to bear to the whole world. On it, as blessed John the Evangelist bears witness when all the disciples were gathered together in one place, and when, the doors being shut, the Lord entered to them, He breathed on them and said: Receive the Holy Ghost: whose sins you have remitted they are remitted to them: and whose you have retained, they shall be retained [Joh 20:22-23]. On it lastly the Holy Spirit that had been promised to the Apostles by the Lord came: and so we know it to have been suggested and handed down by a kind of heavenly rule, that on that day we ought to celebrate the mysteries of the blessing of priests on which all these gracious gifts were conferred.

Liturgical scholars of the 1800s and 1900s, such as Servant of God Dom Prosper Guéranger6 and Blessed Ildefonso Schuster,7 Archbishop of Milan, when reconstructing the Ember Saturday Ordination Liturgies, stated that the Ember Saturday Ordination Masses began late Saturday, with the ordinations occurring on Sunday itself, around dawn. Similar conclusions were made about the Easter Vigil.8 More recent scholars, however, such as Mr. Gregory DiPippo (see, for example, here, and here) have argued that this reconstruction is flawed and that these ceremonies, even starting late Saturday, would have concluded well before the midnight between Saturday and Sunday. This position, expressed by Mr. DiPippo, more closely matches with the explanation given by Pope St. Leo. In fact, in his Letter, Pope St. Leo had to explain that it is possible for ordinations to occur on the Sunday itself, so long as the fasting from Saturday has not been broken. If ordinations regularly occurred on the Sunday itself, such an explanation would be superfluous. The misunderstanding of earlier liturgical scholars no doubt contributed to the rubric promulgated under Venerable Pope Pius XII that things were to be so timed that the Mass of the Easter Vigil was to start at or around midnight.

All this having been said, what did St. Thomas mean when he noted that the Masses of the Ember Saturdays and of the Vigil of Easter, could be postponed from None? He simply meant that the Liturgy could start at such a time that it would be closer to sundown on Saturday so that the ordinations would be conferred around or after sunset, for, as St. Leo wrote, “the day of the Lord’s resurrection…is commonly held to begin on the evening of Saturday.” This assertion should not be unexpected as the Christian tradition is that feasts, particularly Sundays, start the evening before. In his Commentary on the Gospel of St. John, St. Thomas, expressing this tradition, wrote:

To elucidate this it should be noted that, the feasts of the Jews began on the evening of the preceding day (Lev 23:5). The reason for this was that they reckoned their days according to the moon, which first appears in the evening; so, they counted their days from one sunset to the next. Thus for them, the Passover began on the evening of the preceding day and ended on the evening of the day of the Passover. We celebrate feasts in the same way…(cap. 13, lect. 1, n. 1730)

Many who pray the Divine Office are used to normal feasts starting with the night office of Matins and concluding, in the evening of the day of the feast, with Vespers and Compline. Feasts of greater rank, however, start the evening before, with the Offices of Vespers and Compline. So major feasts have a first and second Vespers, while those of lesser rank only have one Vespers, which would correspond to second Vespers. But, before the reforms of the mid-twentieth century, the situation was reversed. All feasts would have had first Vespers, while only major feasts would have a second Vespers. In this way, Christian feasts would start the evening before, continuing the ancient tradition expressed by Pope St. Leo and St. Thomas.

This practice may also explain why, in the traditional Easter and Pentecost Vigils, the color changes from Violet to White or Red respectively for the Mass. The Violet expressed that these Saturdays are days of fasting,9 but, once the sun has set, the color changes to mark that, while the Masses are still those of the Vigils, not of the Feasts themselves, they do partake the festal character of the approaching Feasts. Properly, the beginning of these Feasts is their First Vespers, which, in the case of Easter, is incorporated into the traditional Vigil Mass itself.

Traces of the tradition regarding Mass times perdured even into the 20th century. In pre-1962 Missals, the following rubrics are found:

1. Private Masses are able to be said at any hour from dawn to noon, with at least Matins and Lauds having been prayed. [This is in keeping with what St. Thomas said about Masses being said “‘in the first part of the day,’ owing to any necessity.”]

2. Conventual and Solemn Masses, however, ought to be said according to the following order. On Feasts of Double and Semidouble rank, on Sundays, and within Octaves, after the Hour of Terce has been prayed in choir. On Feasts of Simple rank, and on ferias [days with no feasts] throughout the year, after the Hour of Sext [has been prayed in choir]. In Advent, Lent, and on the Ember Days (even within the Octave of Pentecost), and on fasting Vigils, although the days are solemn, the Mass of these times ought to be sung after the Hour of None [has been prayed in choir] (Missale Romanum [1920], Rubricæ generales Missalis, XV — De Hora celebrandi Missam).

Here is preserved the times and distinctions noted by St. Thomas and Durandus. Conventual and Solemn Masses on feast days (feasts of Double and Semidouble rank) would be said mid-morning, and, on non-feast, non-fasting days (feasts of Simple rank and ferias), Mass would be said around noon. On fasting days (Advent, Lent, Ember Days, and fasting Vigils), Mass would be said midafternoon.

It should be noted that in the above rubrics, “Vigil” means a day of proximate preparation immediately preceding a feast and the Vigil Mass is the Mass proper of this preparatory day. This must be distinguished from a Mass celebrated in the evening before a feast day which is liturgically the Mass of the feast. Properly speaking, such a Mass is an anticipated Mass, not a Vigil Mass. An example of a proper Vigil Mass is the Mass of December 24th, which is the Vigil Day of the Nativity of Our Lord.

In addition to the information provided in the above quoted rubrics, the proper instructions given for Ash Wednesday, the Easter Vigil,10 and the Pentecost Vigil in such Missals contain the rubrics that the ceremonies should start after the Office of None has been prayed, indicating they are celebrated on penitential days. For the Feast of the Annunciation, which usually falls during Lent, instructions are given that the Mass is to start after the Office of Terce has been prayed, as it is a feast day.

For the sake of completion, it is worth noting that there are two Masses which do not follow the Terce-Sext-None pattern, namely the First and Second Masses of Christmas. The First Mass of Christmas, the Midnight Mass – which is not the Vigil Mass of the Nativity; the Vigil Mass of the Nativity, referenced above, is said after None on December 24th, or after Terce if this day falls on a Sunday – is said following Matins around midnight for Christ “was literally born during the night, as a sign that He came to the darknesses of our infirmity; hence also in the Midnight Mass we say the Gospel of Christ’s nativity in the flesh” (S.T. III, q. 83, a. 2, ad. 2). The Second Mass of Christmas, the Dawn Mass, is said after Lauds and Prime (the First Hour), for there is a “spiritual birth, whereby Christ rises ‘as the day-star in our hearts’ (2 Peter 1:19), and on this account the Mass is sung at dawn” (ibid.). It is the Third Mass of Christmas, the Day Mass, which is celebrated after Terce, which is most properly the Mass of this Feast.11

In addition to all this, St. Thomas and Durandus noted that during Lent there are “double days,” when two Masses are said. In pre-1962 Missals, after the entry for February 4th in the Proper of the Saints, a lengthy rubric is given on how to proceed during Lent. A portion of this rubric translates as:

Where, however, there is the choral obligation [such as with monks], the Mass of the Feast [of Double or Semidouble Rank] is read extra Chorum, without a Commemoration of the Lenten feria, after the Hour of Terce has been prayed; the conventual Mass of the Feria is said in Choro, without a commemoration of the Feast, after the Hour of None has been prayed…If, however, the feast is a Double of the First or Second Class, the conventual Mass of the Feast is said in Choro, and the Mass of the Feria is read extra Chorum. Private Masses, however, of the Mass of the Feria are prohibited.

Here we see the practice described by St. Thomas and Durandus was still kept where there was a choral obligation, such as in monasteries. When a feast falls during Lent, two Masses would be said – the Mass of the feast in the morning and the Mass of the Lenten feria in the afternoon.

So then, dear reader, the next time you find yourself at Mass, try to identify what type of day it is on the liturgical calendar – a feast day, a non-feast/non-fast day, or a fasting day – and unite yourself to the portion of Our Lord’s Passion associated with the hour at which this Mass would have been said. And thus, you will be joining yourself in spirit with those Roman Christians of so long ago and those religious who, even up to today, still observe the practice of celebrating Mass after Terce, Sext, or None as the case may be. And the next time someone asks “What time is Mass?,” please be sure to share this article.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX. Special thanks are due to Fr. James Smith, FSSP, for his support and encouragement.

- On certain days of the Liturgical Year, the Pope would celebrate the primary Mass for the city of Rome at one of the various churches of the city. The church where this would take place was called the Station.

- The Divine Office is a collection of Psalms, Hymns, and Prayers which are assigned for each day, which are then in turn divided into different “Hours” which historically correspond with different times of the day.

- Durand, William. Rationale IV – On the Mass and Each Action Pertaining to It. Trans. Thibodeau, Timothy M. (Turnhour: Crepols Publishers n.v., 2013), p. 61 (IV, I, 21). Here Durandus seems to be making a distinction between days with penitential kneeling and days without it, a distinction still maintained today. On fasting days or during Masses of a more somber character, those attending Mass kneel for the Collect(s) (opening prayer), from the Sanctus until Communion, standing at the Agnus Dei and Pax, and for the Postcommunion(s) (closing prayer) (“with genuflection”). In the Divine Office, those attending would also kneel for the closing oration(s). On other days, those attending Mass would only kneel for the Consecration and Communion out of reverence (“without genuflection”). As the penitential kneeling would never occur on Sundays, but only reverential kneeling, the 20th Canon of Nicaea I is still observed.

- Schuster, Ildefonso. The Sacramentary, vol. II (Parts 3 & 4). Trans. Levelis-Marke, Arthur. (Waterloo: Arouca Press, 2020), p. 39. For more information about the historical daily breaking of the Lenten Fast, see Mr. Gregory DiPippo’s article here. While reading his article, please note that according to Blessed Schuster, “Vespers did not form part of the Roman cursus until the seventh century” (vol. II, p. 251). This being the case, before Vespers was introduced, the daily Lenten Fast would have been broken immediately following Mass.

- In addition to the Ember Saturdays and Holy Saturday, the Pontificale Romanum [1752 and 1961-1962 editions] also indicates the Saturday before Passion Sunday as a day of Ordination. The rubric reads: “Tempora ordinationum sunt: sabbata in omnibus Quatuor Temporibus, sabbatum ante dominicam de Passione et Sabbatum sanctum.”

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, 5 (Lent). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), p. 179.

- Schuster, pp. 5, 73-74, 141; also Schuster, Ildefonso. The Sacramentary, vol. IV (Parts 7 & 8). Trans. Levelis-Marke, Arthur. (Waterloo: Arouca Press, 2020), p. 18.

- See, for example, Schuster, vol II, p. 29.

- In the 1917 Code of Canon Law, the Vigil of Pentecost was listed as a day of fasting and abstinence (Canon 1252, 2).

- Additionally, another entry in the Decretals indicate that the Mass of the Holy Saturday is to start around the beginning of the night: “In ieiuniis etiam quatuor temporum circa uespertinas horas, in sabbato uero sancto circa noctis inicium missarum solempnia sunt celebranda.”

- That the Day Mass of Christmas is the historic Mass proper to the Nativity of the Lord can also be deduced from evaluating the Stations of each Mass. The Station for the Midnight Mass is St. Mary’s at the Crib, which is a Chapel in St. Mary Major. According to Blessed Schuster “if we are to judge of the number of worshippers by the size of the place in which the station was celebrated, we must conclude that the little crypt ad praesepe [at the crib] would accommodate but very few persons.” As such, this chapel could not accommodate the great concourse of Romans who would be expected to be in attendance on a day of such importance. The Second Mass, the Dawn Mass, is celebrated at the Church of St. Anastasia. Originally, according to Blessed Schuster, this was not a Mass of Christmas but of the Saint herself, as this day was the anniversary of her martyrdom. Only later did the Mass become one of Christmas, with the Martyr commemorated, as is still observed today. It is only the Third Mass, then, held at the Vatican at St. Peter’s which can truly be considered the historical solemn Mass of Christmas.

April 10, 2023