Cardinal Dario Castrillon Hoyos’ Introduction

In introducing the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter Latin Mass training video, Cardinal Dario Castrillon-Hoyos speaks to priests about the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite and comments on the Holy Father Pope Benedict XVI’s motu proprio “Summorum Pontificum.”

January 1, 2012

Christ’s Church: the Four Marks of the One True Church of Jesus Christ

by Fr. Eric Flood, FSSP

by Fr. Eric Flood, FSSP

From the December 2011 Fraternity Newsletter

When we profess our belief in the Church Christ established, we proclaim that it is one, holy, catholic, and apostolic. These four marks must necessarily be present in the religion founded by the God-man. They distinguish false religions from the true one, and, once found in a particular religion, they guarantee the integrity of the doctrines it teaches.

The first mark of Christ’s Church is that it must be “one.” Many today consider themselves to be broadminded when they study various religions and then make a personal decision as to what to believe. Others, however, simply accept—and live according to—the latest creed of the current population. Both of these not only lack a firm foundation upon objective truth, but they are easily influenced by the transitory opinions of the mass media, political agendas, and new “religions.”

But the faith upon which Christ established His Church must—of necessity—have the characteristic of an unending truth enduring throughout the centuries. Christ established His religion upon His own immutability; therefore, its teachings reflect His permanency. When falsity and sin are rampant, Christ’s Church serves as a beacon of light drawing scattered mankind home to unchanging and recognizable truth.

It was to be expected that some men would be bold enough to oppose the teachings of Christ when He walked the earth, but He showed by His example that His teachings would not be influenced by the transitory standards of such men. Similarly, the transient standards of society in the twenty-first century cannot be a reason to call into question the teachings of God. The truth taught two thousand years ago must also be true today.

For instance, consider how, less than a hundred years ago, nearly all the major religions taught that contraception was intrinsically wrong. Now the Catholic Church is virtually alone in upholding that doctrine, while others have changed their teachings in order to acquiesce to modern social thought or to cushion consciences which prefer an easier religion to practice.

True ecumenism, then, strives to build upon the sacred edifice which has Christ as the cornerstone. It does not have a nonchalant attitude towards the proliferation of creeds nor does it ignore certain biblical passages to achieve a common agreement. Similarly, it does not water down the doctrine of Christ; rather, it confidently presents the teachings of Christ in an effort to gather the nations into the one flock.

The oneness of the faith of Christ is further rooted in the unity of God. Christ likens Himself to the good shepherd who watches over his flock. There is only one shepherd, and there is only one flock. Other sheep may be wandering outside the flock who can join the one flock when they attend to the shepherd’s voice. But as Christ shows in the Gospel of St. John (6:67), He will not water down His teachings in order to keep attendance at a high number in His Church.

In His parables, Christ likens the Church to various things: a kingdom, a city, a field, and a vineyard. In every instance, it is a singular thing, not plural kingdoms, cities, fields, or vineyards. Furthermore, the Church is likened to the spouse of Christ (Eph. 5:24-29), but a husband is permitted only one wife. Thus, the Church founded by Christ is one and only one at any given time.

Christ instructed the Apostles to teach “all things whatsoever I have commanded you” (Mt. 28:20). He did not give them permission to change His teachings. Even if the majority of people believed otherwise, or if the truths seemed difficult to believe to the possible converts, the Apostles were to “stand fast in the faith” (I Cor. 16:13) as there is only “one faith” (Eph. 4:5).

Knowing that the truth was in danger of being adulterated, St. Paul also warned of those who “would pervert the Gospel of Christ (Gal. 1:7-8) for “if any one preach to you a gospel besides that which you have received, let him be anathema” (Gal. 1:9). And for those who attempt to pervert the truth, to “mark them who make dissensions and offences contrary to the doctrine which you have learned, and avoid them” (Rom. 16:17).

Christ, too, warned that “there will rise up false christs and false prophets, and they shall show signs and wonders, to seduce, if it were possible, even the elect” (Mark 13:22), and these would be known by their refusal to submit to the Church. “If he will not hear the church, let him be to thee as the heathen and the publican” (Mt. 18:17). For Christ is the same today, yesterday, and forever (Heb. 13:8), and the faithful must be cautious to “be not led away with various and strange doctrines” (Heb. 13:9) for “no other foundation can a man lay, but that which is laid” (I Cor. 3:11).

The abomination of heresy and schism is rooted in the willing withdrawal from unity. But the person who has so withdrawn himself must not be allowed to pretend that he is still “unified.” Hence, unity among the flock of Christ sometimes requires the severing of “dead” members so they do not sap energy from the body of the Church. Furthermore, the oneness of the Church is proclaimed every time it exposes such error or falsity.

Since the Church is one (has a unity) in its principle—God; one in its invisible head —Christ; one in its informing Spirit—the Holy Ghost; one in its aim—Heaven; and one in its communion among members; the unity cannot be broken. Thus, the essence of the Church, being founded upon the rock— Christ, must necessarily have unity.

Unity, then, is an external mark whereby the world can distinguish the false prophets and teachers from the Teacher of truth. This oneness of the Church will persist until the end of time, for even the gates of hell cannot overcome it by instigating division or a multiplicity of religions.

December 5, 2011

The Things That Are Caesar’s – Employing Justice to Render Unto Caesar

by D.Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

From the December 2011 Newsletter

We are all familiar with the response Our Lord gave to the Herodians and Pharisees when, with their typical disingenuousness, they attempted to trap Him in His words over the issue of giving tribute to Caesar. Was it or was it not, they asked, proper for Jews to render such tribute? The Herodians were very probably looking for an emphatic Yes answer, whereas the Pharisees were fishing for an emphatic No. Such it always is with narrow-minded partisans, strangers to wisdom as they are. They know only extremes, and are blind to the possibilities that can lie between them. The answer they received to their question resounds down through the ages, and it is addressed as much to us as it was to them: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

We are all familiar with the response Our Lord gave to the Herodians and Pharisees when, with their typical disingenuousness, they attempted to trap Him in His words over the issue of giving tribute to Caesar. Was it or was it not, they asked, proper for Jews to render such tribute? The Herodians were very probably looking for an emphatic Yes answer, whereas the Pharisees were fishing for an emphatic No. Such it always is with narrow-minded partisans, strangers to wisdom as they are. They know only extremes, and are blind to the possibilities that can lie between them. The answer they received to their question resounds down through the ages, and it is addressed as much to us as it was to them: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

In reflecting on that response, it should be immediately clear to us what it is that we ought to be rendering to God, what it is that we owe to Him. In a word, everything—our whole heart, soul, strength, and mind. “Caesar,” for us, could be said to represent whatever duly established civil government we happen to be subject to. The question then becomes, What is it that we owe to Caesar? What kind of obligations do we have toward the political community to which we belong and the government that guides and directs it?

Before we attempt to answer that question, and to ensure the soundness of the answers we give to it, we have to understand it as having very much to do with the virtue of justice, so perhaps it would be helpful if at this point we were to refresh our memories regarding certain aspects of that most important virtue. We are all familiar with the classic definition of justice, which can be stated as follows: “the rendering to others what is due to them.” Justice is one of the four Cardinal Virtues, but unlike the other three, prudence, fortitude, and temperance, the principal focus of which is inward, on the self, the principal focus of justice is outward, on others. Justice, then, is preeminently a social virtue. It is the virtue which, faithfully practiced, binds human communities together, making them coherent wholes.

Next we recall the three principal divisions of justice, called respectively distributive justice, commutative justice, and social justice. Distributive justice applies to those whom St. Thomas Aquinas describes as “having the care of the community,” which is to say, those who are part of the government in one capacity or another. They have many obligations towards those whom they govern, but the most basic of which, according to St. Augustine, is to establish and maintain a society that is marked by “the tranquility of order,” which is St. Augustine’s definition of peace. But the peace in question must be true peace, that is, peace based on justice. Those who govern must govern justly, which means that they must foster the common good. Commutative justice is the justice which the citizens of a political community display toward one another. And social

justice—sometimes called legal justice—is the just behavior of the citizenry as directed toward those who govern them. We can see, then, that it is social justice which has directly to do with the question of what it is that should be rendered to Caesar.

It is important that we be clear about the fact that what is involved here is a matter of justice, and that implies real obligation on our part. We might be tempted to balk at the idea that we owe anything at all to a government to which we are subject, apart, say, from meeting purely legal obligations such as obeying traffic laws and paying taxes, and in that hand-washing attitude quote from the Letter to the Hebrews to the effect that, “We do not have here a lasting city, but seek one to come.” But such an attitude will not do. True enough, the city in which we now find ourselves is a temporal one, but so long as we ourselves are in time it is the city in which we have been appointed to dwell, and within which, to the best of our abilities given the circumstances, we have to work out our salvation. We cannot, then, shirk the responsibilities we have, in justice, towards those who govern us in the political order.

Nonetheless, we have to admit that we are often confronted with onerous difficulties when it comes to showing an active fidelity toward a government, by freely meeting the obligations we have toward it as citizens, and that is because, we can honestly say, the government, such as it is, is not worthy of our fidelity. The most important obligation of any government, in justice, is to promote a true common good for its citizens, that is to say, to create a cultural atmosphere in which moral virtue is fostered and protected. There are today hundreds of civil governments throughout the world, and most of them fall far short of meeting that obligation. How many of them would even regard it as an obligation? And consider a government that is positively tyrannous, where the people are effectively dehumanized, and rank not so much as citizens but as slaves. What is an honest, conscientious person to do who finds himself in such a situation? St. Thomas argues that the person would be justified in doing all he can to thwart the purposes of the tyrannous regime, and in that would even be showing a foundational kind of fidelity.

St. John Chrysostom, in commenting on the response Our Lord gave to the Herodians and Pharisees, wrote the following: “But when you hear the command to render to Caesar the things of Caesar, know that such things only are intended which in no way are opposed to religion; if such there be, it is no longer Caesar’s but the Devil’s tribute.” Our obligations toward a government do not cease if the government is not what it should be—e.g., if it disregards the common good, if it enacts laws which, because they are contrary to the natural law (the universal moral law) do not even have the status of law and therefore cannot command obedience—but in circumstances such as these the manner in which we meet those obligations takes a new form. We are confronted with a situation where the government is behaving unjustly because it is not meeting its own obligations toward the citizenry. That being the case, the citizens must do everything in their power to return the government to its senses, so that it acknowledges its obligations in justice, and lives up to them. Practically speaking, this would entail effecting a thoroughgoing reform of the government or, if that fails, bringing about a change in government. In the end, the most valuable tribute we can render to Caesar is the coin of justice.

Archbishop Prendergast Confers Minor Orders

On Sunday, November 13th, Archbishop Terrence Prendergast, of the Archdiocese of Ottawa, Canada, conferred minor orders on a number of seminarians from Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary in Nebraska. The orders conferred were those of Porter/Lector and Acolyte/Exorcist, and took place in the beautiful chapel of Sts. Peter and Paul at the seminary. Our great thanks to His Excellency for his generosity in presiding over the ceremony.

Please keep these men in your prayers as they continue in their path of formation and preparation for the holy priesthood.

For more photos, please visit the Seminary website.

November 17, 2011

Bishop Bruskewitz Confers Tonsure

On Saturday, October 22nd, Tonsure was conferred on sixteen seminarians of Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary by His Excellency, Bishop Fabian Bruskewitz, of the Diocese of Lincoln. The ceremony took place in the seminary chapel of Sts. Peter and Paul. Please pray for these men and all the priests and seminarians of the Priestly Fraternity.

For more photos go OLGS Seminary News

November 8, 2011

The Common Good: State Identity and the Cultivation of Virtue

By D.Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

By D.Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

From the November 2011 Fraternity Newsletter

What is the common good? As the very name indicates, it is a good that is shared by many, and as such it stands in contrast to the individual good, a good that is peculiar to this or that person. One can say that any organized “society,” such as the family, an army, or a religious order, is bound together by a common good.

Strictly speaking, however, when we speak of the common good we have in mind that good which is the defining mark of a political society, or state. The common good is the final end of a state, in that it explains the very purpose for which the state was organized.

The common good is essentially a moral good, which is to say that it is a good which, once established and faithfully adhered to, enables the members of a political community, the citizens of a state, to live virtuous lives. Everything having to do with the structure and the running of the state, its constitution, the whole body of its laws, should contribute to the fostering of virtue. Such was the opinion of Plato and Aristotle, and of St. Thomas Aquinas as well. How many modern legislators, one might wonder, would view the matter in that light?

Laws, then, as the expression of the common good, are intended to make people good, but they can do so only if they are good laws, otherwise they will have just the opposite effect. The explanation for a situation where a state has developed the practice of promulgating bad laws is to be traced to a defective common good. It may be called “good” by such a state, but that is to misname it.

To understand this, we need to recall a basic distinction we make in ethics between a true good (bonum verum) and an apparent good (bonum apparens). St. Thomas gives considerable stress to the point that in all of our moral choices we always choose what we perceive to be good. We are constitutionally incapable of choosing evil just as evil. It may in fact be evil, objectively considered, but we have to “translate” it in our minds, making it out to be something good, before we can actively will it. If this happens on the individual level, it happens on the social level as well, with respect to the common good. A political community can set in place and dedicate itself to a common good which is not a true good but an apparent good only. And when that happens the political community in question is heading for disaster.

The common good, we said, is to be contrasted with the individual good, but the two should work together harmoniously. The common good, the good shared by the entire political community, must support and enhance the individual good, and in no way inhibit it. And the individual good of any particular citizen should not be at variance with the common good. And those smaller societies which are included within the embrace of the larger society which is the state, especially the family, should have their proper goods protected and nurtured by the common good. There should be no conflict between the good of the whole and the goods of the parts of the whole.

In recent times we have witnessed a number of governments who have operated under a perversely distorted understanding of the common good. I have in mind those totalitarian regimes which did anything but foster a genuine common good, for, first of all, they certainly were not intending to create a virtuous citizenry, and, second, far from preserving and protecting the individual good, they did everything they could to suppress it.

These governments allowed only for a single, monolithic “good” which tolerated no competitors, and to which everyone had slavishly to conform. If any individual attempted to pursue a good that was antithetical to the pseudo-good of the Party or the Cause, prompt and often lethal action was taken against him.

The common good, again, is a good which is shared by many. It is not exclusively my good, nor yours; it is ours. The common good is what binds a society together; it is a unifying factor, making a political community a coherent, integral whole. This being the case, any movement within a civil society that has the effect of undermining its unity, such as programs that seek to promote “diversity” and “pluralism,” can be said to militate against the common good.

Aristotle defined an oligarchy as government by the rich. An oligarchy would be a defective form of government because it is incompatible with a genuine common good, benefiting, as it does, not the whole society, but only a small part of it. Another defective form of government cited by Aristotle was what he called “extreme democracy”; this is a democratic government which has run amok. What chiefly characterizes extreme democracy is the dominant influence within it of a false idea of freedom, where what is called freedom is really little more than license. In extreme democracy extreme individualism — i.e., sheer selfishness — reigns, with the result that individual goods are pursued to the extent that the common good is blithely ignored.

A current and fairly prevalent misunderstanding of the common good has it that it is no more than the sum total of individual goods. The poverty of such a notion consists in the fact that it fails to recognize the common good precisely as common. One can sum up individual goods from now to Doomsday and never arrive at a common good, for the individual good and the common good are different in kind. An individual good, by definition, is proper to one person; a common good, by definition, is a good shared by many.

The good is the proper object of the human will. It is that for which we were created, and the attainment of which makes for true human fulfillment. All goods, if they are true goods, derive their identity and desirability from the fact that they have their ultimate source in the Supreme Good, God Himself. In the final analysis, then, the test of whether or not any political community is guided by a genuine common good is to be found in the degree to which that good is rooted in a dedication to the Supreme Good. The good that is common to any state should be the same good that is common to the whole of humanity.

November 5, 2011

Video: Fr. Lee on Life on the Rock

On Friday September 22nd at 10:00 p.m., Fr. Joseph Lee, FSSP will appeared on EWTN’s Life on the Rock to talk about Juventutem.

On Friday September 22nd at 10:00 p.m., Fr. Joseph Lee, FSSP will appeared on EWTN’s Life on the Rock to talk about Juventutem.

Here is video from the appearance:

About Juventutem:

Juventutem is an international movement of young Roman Catholics of the ages 16 to 30 who are attached to the Traditional Latin Mass. The aim of the society is to foster and strengthen relationships between these young people at the national and international levels, and to encourage and assist them in developing their faith.

October 4, 2011

The Parables of Christ Part X: Parable of the Great Feast

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the September 2011 Newsletter

Some exegetes claim that the parable of the Marriage of the King’s Son (Matt. 22:1–14) is the same as the parable of the Great Supper (Luke 14:16–24), but the overwhelming majority of scholars deny it. The similarity between the two is that those who were first invited refused the invitation and their places were taken by strangers from the highways.

The differences, however, set them apart. In Luke’s parable the one who invites the guests to his supper is not a king and the guests who refuse the invitation do not abuse the messengers. Unlike Matthew’s parable where the king burns the city of the rebels who maltreated and killed his delegates, the only retribution given in Luke’s parable is that “none of those that were invited will taste of my supper” (Luke 14:24). Moreover, it is only in Matthew’s parable that the king orders the guest who entered the banquet hall without a wedding garment to be bound hand and foot and thrown into the outer darkness.

The parable of the Marriage of the King’s Son presents two difficulties. First of all, why would those invited to the wedding feast injure and even kill the messenger? Secondly, how could a stranger suddenly invited to a wedding feast be justly punished for not wearing a wedding garment?

In answering the first question, Fr. Leopold Fonck, S.J. explains that accepting such an invitation signified loyalty to the king. It is, consequently, true to life that those who had planned a revolt would express their dissatisfaction with the king by maltreating his messengers.

As to the second, the man, by not answering the king’s question, indicates his guilt (Matt. 22:12). This, says Father Fonck, “proves that the prince had given those strangers who had come from the highways time and opportunity to garb themselves suitably for the royal feast (Parables of the Gospel, p. 368).

The parable, which is divided into two parts, illustrates in its first part that the Jews who had spurned the divine invitation were rejected in favor of the Gentiles. In the second part it demonstrates that the condition of holiness is necessary for entrance into eternal life.

The wedding feast which the king prepared for his son and the son’s bride is an image of the everlasting happiness that the eternal Father has prepared for the members of the Church, the Mystical Bride of His Son, Our Lord Jesus Christ. Those invited first were the Jews who imprisoned the Apostle Peter, five times scourged the Apostle Paul, and killed both John the Baptist and James the Greater. As a punishment for their outrageous rebellion, the city of Jerusalem in a.d. 70 was destroyed by the Romans, fulfilling the prophesy of Christ.

In the second part of the parable, which corresponds with the call of the Gentile peoples, the king’s servants are ordered to invite whomever they shall find at the crossroads, bad as well as good. Saint Augustine observed that the first invited who excused themselves from the feast were bad, but in this second group only those who wear the wedding garment are good. The wedding garment, he says, is charity, and it belongs to those who do not seek their own but rather the things of Jesus Christ.

Because none of those invited in the first part were found worthy, and only one of those invited in the second part was found unworthy, Father A. Jones believes that the remark “many are called but few are chosen” (Matt. 22:17) refers to the whole parable but not to either of its parts (c.f. A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture, p. 891). “The majority of the (Jewish) people,” he writes, “by their own fault, are deprived of salvation, but a remnant of Israel will yet share therein” (c.f. Romans 11:25). In his commentary the renowned Fr. Cornelius A. Lapide, S.J. observes that both faith and charity are necessary for salvation. The Jews who rejected Christ lacked faith, without which “it is impossible to please God,” but although the man without the wedding garment had faith, he lacked charity and so was cast into the outer darkness.

September 5, 2011

Parables of Christ Part IX: Parable of the Wicked Tenants

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the August 2011 Newsletter

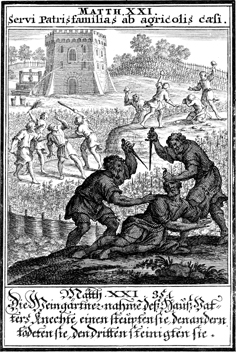

The parable of the wicked husbandmen is one of a select few which are found in all three synoptic Gospels. At Mass on the Friday after the second Sunday of Lent it is read from Matthew. Though it is not without its difficulties, the point of the parable—i.e. the rejection of Jewish leaders and those who followed them—was clearly understood by the chief priests and Pharisees who “knew that he spoke of them” (cf. Mt. 21:45; Mk. 12:12; Lk. 20:19).

In the parable Our Lord says that a man let out his vineyard to husbandmen but when he sent his servants to request his share of the harvests, the servants were beaten and treated shamefully; some were even murdered. Lastly, the owner sent his only son who was cast out of the vineyard and killed.

In Mark and Luke, Christ tells his audience that the owner “will come and destroy those husbandmen and will give the vineyard to others.” In Matthew the audience, in response to Christ’s question about what the owner will do to punish such wickedness, replies: “He will bring those evil men to an evil end; and will let out his vineyard to other husbandmen who will render him the fruit in due season” (Mt. 21:41).

In his book, The Parables of the Gospel, Father Leopold Fonck, S.J. observes that the Jews whom Our Lord was instructing were familiar with the image of the vineyard. Isaias had written: “For the vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel” (Isaias 5:7). In speaking of the vineyard, therefore, Christ is talking about the Kingdom of God which in the Old Testament was identified with the House of Israel.

The owner of the vineyard who planted it with care is the Lord God and the messengers are the prophets whom He sent to His people. These men were treated shamefully and their message rejected. Jeremias 20:2, for example, says: “And Phassur struck Jeremias the prophet and put him in the stocks that were in the upper gate of Benjamin, in the house of the Lord.” Some were even put to death. Speaking of the prophet Urias, Jeremias writes: “And they brought Urias out of Egypt: and brought him to king Joakim, and he slew him with the sword: and he cast his dead body into the graves of the common people” (Jeremias 26:23).

When the wicked husbandmen kill the only son of the vineyard owner, their destruction is sealed. Christ, the Word made flesh, is the only Son of the Eternal Father who by means of this parable prophecies that He will be slain by the leaders of the Jews. Pontius Pilate indeed sentenced Our Lord to death but— in the words of Saint Augustine—the Jews slew Him with the sword of their tongue when they cried out to the Roman governor: “Crucify Him.” Because they rejected the Messiah, the kingdom of God is taken from them.

Christ calls Himself the cornerstone because He unites Jews and Gentiles in His Church. “And whoever falls upon this stone,” He says, “will be broken: but on whomever it shall fall, it shall grind him to powder.” In his interpretation, Father Fonk writes: “As a light potter’s vessel, if it strikes against a big stone or is hit by it, in either case is smashed to pieces, so the rejected Messiah will prove the temporal and eternal destruction of Israel.”

Father Cornelius A. Lapide, however, says that the one who falls on the stone shall bring harm to himself but in such a way that the harm may be repaired by repentance. The one on whom the stone shall fall can have no hope of reparation or restitution. Saint Thomas Aquinas, referring to Saint Jerome’s commentary, says that the one who falls on the stone is one who believes in Christ but falls on Him by committing serious sins, but the one on whom the stone falls is the one who who does not believe. A salutary application of the parable was made by Alphonsus Salmeron, S.J., one of the original companions of St. Ignatius of Loyola who became an outstanding biblical scholar. “For what the Lord predicted would happen to the Jews,” Salmeron said, “we see also to have happened in many Christian nations in Africa, Asia and in Greece.” This same application was made even more trenchantly by Bishop Cornelius Jansen, a scriptural scholar who attended the last session of the Council of Trent, “It is to be feared,” he wrote, “that the same thing happen to us, if, as many in this part of the west have already been affected, they continue to hold in contempt ecclesiastical teaching which venerable antiquity has handed down to us listen instead with itching ears to those who speak novel teachings.”

August 5, 2011

The Priest as Sacrifice and Victim: the Sacrificial Nature of the Sacred Priesthood

by Fr. Eric P. Flood, FSSP

by Fr. Eric P. Flood, FSSP

From the August 2011 Newsletter

As priests are to “offer up gifts and sacrifices for sins” (Heb. 5:1), Christ, the Eternal High Priest, being perfect, could offer only the most perfect Sacrifice in atonement for sin. Since there is no greater sacrifice than to lay down one’s life, He sacrificed Himself during His passion and death upon the Cross for the salvation of mankind.

This one Sacrifice is continually presented to His Father in the heights of Heaven and is made present on earth every time a Catholic priest offers Holy Mass. The greatest glory of the priesthood is approaching the altar, in imitation of Christ, and offering the same Sacrifice, although in an unbloody manner.

But the example of Christ also shows that the priest is more than one who offers a Sacrifice upon the altar: he is also one who is to be sacrificed for the salvation of souls. Our Lord’s example of rising from the dead and ascending into Heaven only after a life of sufferings and toil indicates to every subsequent priest what to expect in this life.

“If any man will come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow Me” (Mt. 16:24). As the life of Christ was a constant series of privations, humiliations, fatigue, and labors from Bethlehem to Calgary, so too will be the life of the priest. If the student is to become as the Master, the sufferings in this life need to be received in a spirit of gladness and joy for the glory of God and the salvation of souls throughout the world.

As Christ was sacrificed as the Paschal Lamb, unblemished and unspotted, He was led to the shearers without uttering a sound. Now, men raised to the dignity of the priesthood have the duty of living a holy life, and, if necessary, following the slain Lamb to martyrdom.

It is necessary, then, for those discerning a vocation to the priesthood to understand this notion of being willing to offer one’s life to God and to embrace suffering and labor in a spirit of charity. The formation of seminarians needs to inculcate this true spirit of sacrifice so that each candidate comprehends his life as no longer his own.

The priesthood is not like a secular job in which one decides his profession; rather, the priest is chosen by God (Heb. 5:4). The man does decide to embrace God’s calling or not, but such a pursuit cannot be for selfish reasons such as money, recognition, or an easy life.

The history of the Church shows what happens when priests do not live their priesthood in imitation of the suffering Christ, for it spills over into the lives of the faithful. The adage goes as follows: a holy priest yields a fervent parish; a fervent priest yields a good parish; a good priest yields a lukewarm parish; and a lukewarm priest yields a cold parish.

But few are those who are willing to persist in a life of suffering joyfully for the Church. Christ Himself declared this when He said that “many are called, but few are chosen” (Mt. 22:14). Whereas God always provides for the Church in calling a sufficient number of men to be priests, oftentimes there is not a shortage of priests; rather, only an insufficient number of good and holy priests willing to suffer in imitation of Christ.

And the sufferings can be immense and varied, ranging from physical deterioration and ailments to the venom of tongues found in false accusations and ridicule. Hence, one of the marks of a vocation to the priesthood is the willingness to learn how to suffer out of love for God.

As a result, seminaries are often nicknamed “The School of the Cross.” Priests who survived imprisonment at Dachau in World War II afterwards professed that the priesthood was better understood by what they had to suffer.

Thus, the burdens placed upon a priest’s shoulders become a fitting preparation for the next time he celebrates Holy Mass. And his life in conformity to Christ Crucified transforms his daily burdens into light and sweet labor.