Camp Isaac Jogues a Success!

The second annual Camp St. Isaac Jogues, held at the Fraternity’s beautiful headquarters in the rolling Pocono Mountains of Northeast Pennsylvania, was again a great success! 26 boys attended the camp this year from July 13-23, where they experienced daily mass, catechism, and a variety of sporting and athletic activities. Fr. Simon Harkins, FSSP, and Deacon Mr. Kevin O’Neill, FSSP, were assisted by six seminarians from Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary in making sure the boys enjoyed a proper balance of spiritual and athletic experiences in a youthful and exuberant Catholic environment.

July 28, 2011

Parables of Christ Part VIII: the Hidden Treasure and Leaven

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the July, 2011 Newsletter

The expression “kingdom of heaven” is used by Saint Matthew 33 times; and the expression “kingdom of God” is used 32 times by Saint Luke, 14 times by Saint Mark, and twice by Saint John. According to the renowned biblical scholar, Father Ferdinand Prat, S.J., these expressions are synonymous. This becomes obvious by comparing Matthew 13:11 (“To you it is given to know the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven…”) with Mark 4:11 (“To you it is given to know the mysteries of the kingdom of God…”) and Luke 8:10 (“To you it is given to know the mystery of the kingdom of God…”). It is the opinion of Father Joachim Salaverri, S.J., an expert on Fundamental Theology, that “kingdom of heaven” was used by Matthew because his Gospel was written for the Jews who were “accustomed to refrain from professing the unutterable name of God and substituted heaven for it” (BAC Sacrae Theologiae Vol. I, p. 516). In the other Gospels, written for the Gentiles who were unfamiliar with Jewish tradition, “kingdom of God” would be more easily understood.

Both expressions refer to the universal kingdom announced in the Old Testament and established by Christ in the New.

Among the many Old Testament passages which proclaim that the Gentiles would also enter into God’s kingdom, the following are illustrative: Isaias 2:2 (“And in the last days the mountain of the house of the Lord shall be prepared on the top of the mountain, and it shall be exalted above the hills, and all nations shall flow into it”); Psalm 71:11 (And all the kings of the earth shall adore him; all nations shall serve him”); and Malachias 1:11 (“For from the rising of the sun even to the going down, my name is great among the Gentiles, and in every

place there is sacrifice, and there is offered to my name a clean oblation: for my name is great among the Gentiles, saith the Lord of hosts”).

Matthew says that after John baptized Him, “Jesus began to preach and to say: Do penance, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (4:17). Recording the same incident, Mark writes: “Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel of the kingdom of God and saying: The time is accomplished and the kingdom of God is at hand: repent and believe the gospel” (1:14–15).

It is the kingdom of God or certain aspects of it that Christ explains in His parables. In the parables of the dragnet and of the wheat and the cockle, for example, He reveals that the kingdom of God exists both in this world and in the next. In this world it comprises both the good and the bad, but in the next life it will consist only of the just.

It is the kingdom of God or certain aspects of it that Christ explains in His parables. In the parables of the dragnet and of the wheat and the cockle, for example, He reveals that the kingdom of God exists both in this world and in the next. In this world it comprises both the good and the bad, but in the next life it will consist only of the just.

Our Lord further compared the kingdom of God to the mustard seed which was the smallest seed in any Palestinian garden but which grew in a short time to tower above all the other vegetable plants. It was in a very short time that the kingdom of God built on the apostles spread throughout the Roman Empire. Those Jews who converted to Christ after hearing Peter’s Pentecost sermon, for example, were “Parthians, Medes and Elamites.” They lived in “Mesopotamia, Judea and Capadocia, Pontus and the province of Asia, Phrygia and Pampylia, Egypt and the regions of Libya around Cyrene.” Some were “even visitors from Rome” (cf. Acts 2:9–10). With the conversion of the Roman centurion Cornelius, the

realization of a universal kingdom embracing Jews and Gentiles had begun.

A companion parable, that of the leaven, announces that by a mysterious hidden power, what is sown in men’s souls like a seed will transform them. As evidence of this transformation Eusebius of Caesaria (d. a.d. 341) writes in his Preparatio Evangelica: “…The Sythians no longer feed on human flesh because the message of Christ has penetrated their region; nor do other races of barbarians still defile themselves by incest with sisters and daughters; …nor do they pursue other pleasures of the body which violate the laws of nature; nor do they give the corpses of their neighbors to be eaten by dogs and birds, as they once did; nor do they make sacrificial offerings to the demons as if to gods, as was proscribed by their ancestors.”

Since the kingdom of God can endow men with supernatural virtue in this life and eternal happiness in the next, Our Lord compares it to a treasure hidden in a field and to a pearl of great price. As the man who found the treasure in the field sold all that he had to purchase it, so must we willingly and joyfully give up all things to possess the kingdom of God.

July 5, 2011

Parables of Christ Part VII: the Parable of the Prodigal Son

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the June, 2011 Newsletter

In his analysis of the Prodigal Son, Father Leopold Fonck, S.J. says that there are two parts to the parable. The first part concerns the fall of the younger son into evil ways and his conversion. The second part treats of his reception in his father’s house. Both parts are further divided into sections. The first has three: the younger son’s leaving his father’s house, his life in a far off country and his conversion. The second part has two sections: the young man’s reception by his father and his reception by his older brother.

It is the father’s magnificent forgiveness of his younger son who had so grossly offended him which silences the objection the scribes and Pharisees had made about Christ, i.e. “This man welcomes sinners and eats with them” (Luke 15:2). As Father Fonck writes; “What is it that He (Christ) would engrave so deeply on the heart of his hearers save the great truth of the inexhaustible love and mercy of the Heavenly Father for the sinful yet repentant child of earth — that love and mercy which He Himself had come to proclaim to the world by His words and still more by His example” (Parables of the Gospel, p. 782). The comparison between the mercy of the earthly father for hi contrite son and the mercy of God for His contrite children is, of course, the essential point of the parable.

But what of the reception given by the older brother? Does this have any relation to the central idea of the parable? Some have identified the elder brother with the Pharisees but others recognize that unlike the Pharisees whom Christ rebukes for their hypocrisy, the elder brother is not contradicted when he protests his fidelity to his father. Because his criticism of his father’s rejoicing over the return of the prodigal manifests anger and envy, the older brother is not, however, without fault. Baffled by these considerations. many other commentators regard the behavior of the elder brother as an incidental feature which has no correspondence to the parable’s supernatural meaning. But how can so integral a section lack significance?

In a sermon entitled “Contracted Views of Religion” Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman points out that the reaction of the elder brother springs from “perplexity” and “distress of mind.” What was the use of serving his father dutifully “if there were no difference in the end between the righteous and the wicked?” “At first sight,” the Cardinal continues, “the reception of the penitent sinner seems to interfere with the reward of the faithful servant of God.”

In his gentle response to his son’s outburst the father assures the elder brother that there is a difference between obedience and rebellion. “Son,” he said, “thou art always with me and all that is mine is thine.” What the father is telling him, Newman says, is this: “why this sudden fear? Can there be any misconception on thy part because I welcome thy brother? Dost thou not yet understand me? Surely thou hast known me too long to suppose that thou canst lose by his gain. Thou art in my confidence. I do not make any outward display of kindness towards thee, for it is a thing to be taken for granted. We give praise and make professions to strangers not to friends.” (Parochial and Plain Sermons, p. 547)

“But we were bound to make merry and rejoice,” the father insists, “for this thy brother was dead , and has come to life; he was lost and is found” (Luke 15:32). These words, Newman says, “contain a consolation for the perplexed believer not to distrust Him.” They also underscore what Christ had said earlier in the same chapter at the conclusion of the Parable of the Lost Sheep: “I say to you that, even so, there will be joy in Heaven over one sinner who repents more than over ninety-nine just who have no need of repentance” (Luke 15:7). †

June 5, 2011

Identity in Ad Orientem Worship

(Originally from the June, 2011 Fraternity Newsletter)

(Originally from the June, 2011 Fraternity Newsletter)

There are scientific ways of knowing the identity of a person, such as fingerprinting, retinal scans, or DNA analysis; however, in everyday life, the identity of a person is by his face. It may happen that we see a person from behind or from a distance and think we know who it is, but until we see the face, the identity of the person can remain in doubt.

The human face is so unique that, except for identical twins, we instantly know who a person is merely by sight of it. Furthermore, we often associate everything we know about the person by the face. His abilities, personality, and past shared experiences become so much a part of his face so that even the person’s reputation and name are tied to it.

By means of the face, we also ascertain how a person must be feeling at the moment. The countenance indicates whether a person is sad, upset, content, or joyful. Likewise, the face expresses what is even deeper inside the person, such as moods, dispositions, likes, and dislikes.

Close contact with the face of another person expresses intimate love, while not showing one’s face or “turning one’s back” on another person expresses anger, disappointment, or contempt.

A conversation is personal when conducted face-to-face, but the same conversation loses its familiarity when the parties are speaking on the telephone or across the room from each other. Talking while being occupied with something else is considered not giving our full attention, and speaking with one’s back towards the person is considered rude or insulting.

Turning, then, to our conversation with God — prayer — it is best realized only in Heaven where it will be face-to-face, but until then, it helps to picture the Person with Whom we are conversing. Hence, while praying, when the mind focuses upon an image of God, whether internally or externally, we better maintain our attention.

In order to assist us at the greatest prayer, Holy Mass, we face the Altar upon which the Sacrifice of Calvary is made present, and, together with the priest, we adore and beseech God. The entire congregation and priest focuses upon God, and our posture and visage are directed in such a way as to face the One with Whom we are speaking. As a result, the posture of the faithful should not be considered as facing the priest; rather, facing God, since Mass is not a conversation with the celebrant, but the Triune God.

While the priest offers Mass, he does everything possible to show respect, maintain attention, and not lose sight of the great action before him while he concentrates upon the prayers given him to say. To assist him, he faces heavenward, beseeching the Blessed Trinity on behalf of his flock.

Thus, he does not have his back turned towards the people; rather, the priest is facing the same direction as the rest of the community who are facing God. As we do not take offense by the person who has his back towards us in the pew in front of us, so too, there is no offense when the priest has his back towards us as we are all praying to the same Blessed Trinity, and all faces are directed toward Him to Whom we are speaking.

To take this analogy one step further, if, perchance, the person in the pew in front of us turned around and faced us, we would expect him to say something. Likewise, when the priest at Mass turns towards us, we expect his words to be directed at us; otherwise, it is obvious that he is speaking to someone else at those times he is faced in the same direction as everyone else in the church.

By having the priest face God during Mass, there is the additional benefit of the identity of his human nature diminishing when his face is not seen. During Mass, the priest acts in persona Christi, so that the less we see the face of the priest, the more his personality and identity subside. Consequently, our minds more easily focus upon the occurring holy actions and sacred mysteries as we avoid attention given to any concomitant human elements.

As mentioned above, at those times when the priest faces the faithful, such as the sermon, we instantaneously realize to whom these words are directed. However, to avoid the atmosphere becoming too “humancentric,” the priest maintains a dignified mannerism even at these times, in imitation of Christ preaching to the faithful of His time.

Yet, arriving at the most solemn parts of Mass, when our attention is most directed towards God (ad orientem), all our efforts—internal and external—are united in adoring and praising the Triune God in the most sublime and reverent manner.

Awaiting, then, the happy state of the elect who see God face-to-face in the beatific vision, our conversing with God on earth ought to be shown by humble and reverent attention, love, and devotion. Doing so will prepare our soul never to lose sight of God for all eternity.

May Ordination Videos from OLGS

Below is video of the recent ordinations which took place in May at Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary according to the traditional rite of ordination. You can also view these videos on the seminary’s new YouTube channel.

Below is video of the recent ordinations which took place in May at Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary according to the traditional rite of ordination. You can also view these videos on the seminary’s new YouTube channel.

Video I

Video II

Video III

Video IV

Video V

Video VI

Video VII

Video VIII

Video IX

Video X

June 3, 2011

Spiritual, But Not Religious – Distinction, or Rationalization?

by Dr. Dennis Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

by Dr. Dennis Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

(Originally in the June 2011 Fraternity Newsletter)

Our fast dimming and drifting culture would seem to have given rise to a new distinction — or at least it has come up with a new name for what is really an old and rather tired bit of rationalization — and it is one which, at least according to those who are most apt to appeal to it, is to be taken as having deep significance. It is the distinction between being religious and being spiritual. How is the distinction to be understood, from the point of view of those who propound it and presumably guide their lives by it?

I will put myself in the shoes of one of its advocates, and thus try to explain it to you in a manner he would be likely to adopt. “To begin with, you must not suppose that the distinction refers to two modes of being which, though different, are to be considered as quite equal. Not at all. Being spiritual is definitely superior to being religious. I don’t want to be unduly hard on religious people, but facts are facts and they must be faced up to squarely. Religious people represent a type which, because of their seemingly ungovernable superficiality, their lack of inner substance and creative self-reliance, need to associate themselves with like-thinking and like-acting people so as to preserve and protect whatever tenuous self-identity they have managed to retain. And, let’s be honest, religious people have a long, sad history of hypocrisy behind them, by which they are more than a little tainted. They go through the motions, they avow to believe this, that or the other thing—and some of those beliefs, it has to be admitted, are, taken in themselves, somewhat noble—but there is an embarrassing discrepancy between their beliefs and their actions. In a word, they lack integrity.

“Believe me, I know this firsthand. You see, I was brought up in a religious family, to be specific, I was baptized and brought up a Catholic. Not only that, all my education was in Catholic schools—grade school, high school, even college. However, I’ve left all that behind me. I am no longer religious, but I am, mind you, a spiritual person. You religious people, especially you Catholics, are probably shaking your heads at that, and feel sorry for me. Don’t. You may think that by ridding myself of religion I have retrogressed, but in that you think wrongly. Rightly regarded, my life has to be seen as an example of real progress, for to be spiritual is to have advanced oneself to a higher plane of reality.

“What does it mean to be spiritual, as opposed to being religious? Well, it’s not the easiest thing in the world to explain, but I will give it a try. To be spiritual is first of all to be honest with yourself, to do what you think is the right thing to do, and not what other people tell you is the right thing to do. It is to be guided by one’s innermost self. To be spiritual is to be able to appreciate all the good things of life, to be able to enjoy things with an open heart and an open mind, in a spirit of non-judgmental tolerance. It means to be grateful. A spiritual person is energized and led by a lively sense of the transcendent; he has this keen feeling that there is Something out there which is very big and very mysterious and very wonderful. As a spiritual person I appreciate the higher things in life—music, poetry, the beauties of nature. And of course there is love, which is supreme. I love everybody, and I ardently wish that everybody would love everybody.”

The above description represents, I think, a reasonably accurate description of the mind-set of someone who would identify himself as spiritual, but not religious. What are we to make of it? First of all, we have to say that, if the terms which compose the distinction are to be correctly understood, it is entirely specious, for if one is genuinely religious one cannot but be genuinely spiritual. Obviously, the spokesman for the “being spiritual” position from whom we have just heard has a very poor grasp on what it means to be religious, and hence his understanding of spirituality is necessarily anemic and mushy.

So, we must clarify a very important term, by asking: What does it mean to be genuinely religious? But before addressing that important question I want to make a brief comment on the fact that our spokesman was raised a Catholic, that, indeed, as he pointed out, he is a product of Catholic schools, all the way through college. Now, as it happens, there are not a few young Catholics today who are in the same boat as our spokesman. They have been raised Catholics, but they have abandoned their faith, opting for an arid, quasi-pantheistic New Age No-Man’s- Land, a territory which seems to have become a favorite camping ground for many in our secularistic age. Because these people are adults, possessed of the use of reason, and because their decision was freely made, they are the ones who are ultimately responsible for it. But given what has been the general state of Catholic education over the past four decades and more, given what has happened to catechesis during that same period, I would argue that those young Catholics are not entirely to blame for the unfortunate state in which they find themselves. The responsibility for their plight must extend to those Catholic educators and catechists who seemed to have been doing everything but passing on the faith to those who were entrusted to their care.

What, then, is religion? Father John Hardon, typically, gives us a crisply precise definition. Religion is “the moral virtue by which a person is disposed to render to God the worship and service He deserves.” The virtue of religion is a particular manifestation of the larger virtue of justice. To be just is to render to another what is due to the other. What is due to God? Everything, for everything, including our very being, comes from Him. To be religious is not easy; in a way it can prove to be the hardest thing in the world, for by it we must overcome that tenacious and ever-pressing temptation to put ourselves above all else, even God Himself. To be religious is ever to strive to fulfill, day in and day out, the two greatest commandments: love of God and love of neighbor. It is what we were made for.

To claim to be spiritual but not religious has a high sounding ring to it—that’s the intended idea—but in reality it is simply an overly self-conscious effort to take the moral high ground by dint of clever rhetorical wordplay. Though empty of serious meaning, the claim nonetheless represents a ploy which is typical of our disingenuous age, for it represents a common way we have of attempting to assuage our consciences by vesting bad decisions in glittering garments.

June 1, 2011

Priestly Ordinations – May 21st, 2011

On Saturday, May 21, Deacon Matthew McCarthy, FSSP and Deacon Christopher Pelster, FSSP were ordained priests for the FSSP by His Excellency, Bishop Fabian W. Bruskewitz (Diocese of Lincoln) at Saints Peter and Paul Chapel at Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary.

Our gratitude and thanks to His Excellency for ordaining these men to the Holy Priesthood, our congratulations to our new priests and their families, and thanks to all our benefactors and friends who have supported these men and the seminary during the course of their studies with prayers and other assistance. Below are some pictures of the day.

Look for an article and more photographs of the ordinations in an upcoming edition of the monthly newsletter of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter. To receive the monthly newsletter for free, click here to subscribe.

May 25, 2011

Instruction Universae Ecclesiae

The Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter welcomes the May 13 publication by the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei of Universae Ecclesiae, the instruction on the application of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum.

PONTIFICAL COMMISSION ECCLESIA DEI

INSTRUCTION

on the application of the Apostolic Letter Summorum Pontificum of

HIS HOLINESS POPE BENEDICT XVI given Motu Proprio

I. Introduction

1. The Apostolic Letter Summorum Pontificum of the Sovereign Pontiff Benedict XVI given Motu Proprio on 7 July 2007, which came into effect on 14 September 2007, has made the richness of the Roman Liturgy more accessible to the Universal Church.

2. With this Motu Proprio, the Holy Father Pope Benedict XVI promulgated a universal law for the Church, intended to establish new regulations for the use of the Roman Liturgy in effect in 1962.

3. The Holy Father, having recalled the concern of the Sovereign Pontiffs in caring for the Sacred Liturgy and in their recognition of liturgical books, reaffirms the traditional principle, recognised from time immemorial and necessary to be maintained into the future, that “each particular Church must be in accord with the universal Church not only regarding the doctrine of the faith and sacramental signs, but also as to the usages universally handed down by apostolic and unbroken tradition. These are to be maintained not only so that errors may be avoided, but also so that the faith may be passed on in its integrity, since the Church’s rule of prayer (lex orandi) corresponds to her rule of belief (lex credendi).”[1]

4. The Holy Father recalls also those Roman Pontiffs who, in a particular way, were notable in this task, specifically Saint Gregory the Great and Saint Pius V. The Holy Father stresses moreover that, among the sacred liturgical books, the Missale Romanum has enjoyed a particular prominence in history, and was kept up to date throughout the centuries until the time of Blessed Pope John XXIII. Subsequently in 1970, following the liturgical reform after the Second Vatican Council, Pope Paul VI approved for the Church of the Latin rite a new Missal, which was then translated into various languages. In the year 2000, Pope John Paul II promulgated the third edition of this Missal.

5. Many of the faithful, formed in the spirit of the liturgical forms prior to the Second Vatican Council, expressed a lively desire to maintain the ancient tradition. For this reason, Pope John Paul II with a special Indult Quattuor abhinc annos issued in 1984 by the Congregation for Divine Worship, granted the faculty under certain conditions to restore the use of the Missal promulgated by Blessed Pope John XXIII. Subsequently, Pope John Paul II, with the Motu Proprio Ecclesia Dei of 1988, exhorted the Bishops to be generous in granting such a faculty for all the faithful who requested it. Pope Benedict continues this policy with the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum regarding certain essential criteria for the Usus Antiquior of the Roman Rite, which are recalled here.

6. The Roman Missal promulgated by Pope Paul VI and the last edition prepared under Pope John XXIII, are two forms of the Roman Liturgy, defined respectively as ordinaria and extraordinaria: they are two usages of the one Roman Rite, one alongside the other. Both are the expression of the same lex orandi of the Church. On account of its venerable and ancient use, the forma extraordinaria is to be maintained with appropriate honor.

7. The Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum was accompanied by a letter from the Holy Father to Bishops, with the same date as the Motu Proprio (7 July 2007). This letter gave further explanations regarding the appropriateness and the need for the Motu Proprio; it was a matter of overcoming a lacuna by providing new norms for the use of the Roman Liturgy of 1962. Such norms were needed particularly on account of the fact that, when the new Missal had been introduced under Pope Paul VI, it had not seemed necessary to issue guidelines regulating the use of the 1962 Liturgy. By reason of the increase in the number of those asking to be able to use the forma extraordinaria, it has become necessary to provide certain norms in this area.

Among the statements of the Holy Father was the following: “There is no contradiction between the two editions of the Roman Missal. In the history of the Liturgy growth and progress are found, but not a rupture. What was sacred for prior generations, remains sacred and great for us as well, and cannot be suddenly prohibited altogether or even judged harmful.”[2]

8. The Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum constitutes an important expression of the Magisterium of the Roman Pontiff and of his munus of regulating and ordering the Church’s Sacred Liturgy.[3] The Motu Proprio manifests his solicitude as Vicar of Christ and Supreme Pastor of the Universal Church,[4] and has the aim of:

a. offering to all the faithful the Roman Liturgy in the Usus Antiquior, considered as a precious treasure to be preserved;

b. effectively guaranteeing and ensuring the use of the forma extraordinaria for all who ask for it, given that the use of the 1962 Roman Liturgy is a faculty generously granted for the good of the faithful and therefore is to be interpreted in a sense favourable to the faithful who are its principal addressees;

c. promoting reconciliation at the heart of the Church.

II. The Responsibilities of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei

9. The Sovereign Pontiff has conferred upon the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei ordinary vicarious power for the matters within its competence, in a particular way for monitoring the observance and application of the provisions of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum (cf. art. 12).

10. § 1. The Pontifical Commission exercises this power, beyond the faculties previously granted by Pope John Paul II and confirmed by Pope Benedict XVI (cf. Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, artt. 11-12), also by means of the power to decide upon recourses legitimately sent to it, as hierarchical Superior, against any possible singular administrative provision of an Ordinary which appears to be contrary to the Motu Proprio.

§ 2. The decrees by which the Pontifical Commission decides recourses may be challenged ad normam iuris before the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura.

11. After having received the approval from the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei will have the task of looking after future editions of liturgical texts pertaining to the forma extraordinaria of the Roman Rite.

III. Specific Norms

12. Following upon the inquiry made among the Bishops of the world, and with the desire to guarantee the proper interpretation and the correct application of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, this Pontifical Commission, by virtue of the authority granted to it and the faculties which it enjoys, issues this Instruction according to can. 34 of the Code of Canon Law.

The Competence of Diocesan Bishops

13. Diocesan Bishops, according to Canon Law, are to monitor liturgical matters in order to guarantee the common good and to ensure that everything is proceeding in peace and serenity in their Dioceses[5], always in agreement with the mens of the Holy Father clearly expressed by the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum.[6] In cases of controversy or well-founded doubt about the celebration in the forma extraordinaria, the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei will adjudicate.

14. It is the task of the Diocesan Bishop to undertake all necessary measures to ensure respect for the forma extraordinaria of the Roman Rite, according to the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum.

The coetus fidelium (cf. Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, art. 5 § 1)

15. A coetus fidelium (“group of the faithful”) can be said to be stabiliter existens (“existing in a stable manner”), according to the sense of art. 5 § 1 of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, when it is constituted by some people of an individual parish who, even after the publication of the Motu Proprio, come together by reason of their veneration for the Liturgy in the Usus Antiquior, and who ask that it might be celebrated in the parish church or in an oratory or chapel; such a coetus (“group”) can also be composed of persons coming from different parishes or dioceses, who gather together in a specific parish church or in an oratory or chapel for this purpose.

16. In the case of a priest who presents himself occasionally in a parish church or an oratory with some faithful, and wishes to celebrate in the forma extraordinaria, as foreseen by articles 2 and 4 of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, the pastor or rector of the church, or the priest responsible, is to permit such a celebration, while respecting the schedule of liturgical celebrations in that same church.

17. § 1. In deciding individual cases, the pastor or the rector, or the priest responsible for a church, is to be guided by his own prudence, motivated by pastoral zeal and a spirit of generous welcome.

§ 2. In cases of groups which are quite small, they may approach the Ordinary of the place to identify a church in which these faithful may be able to come together for such celebrations, in order to ensure easier participation and a more worthy celebration of the Holy Mass.

18. Even in sanctuaries and places of pilgrimage the possibility to celebrate in the forma extraordinaria is to be offered to groups of pilgrims who request it (cf. Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, art. 5 § 3), if there is a qualified priest.

19. The faithful who ask for the celebration of the forma extraordinaria must not in any way support or belong to groups which show themselves to be against the validity or legitimacy of the Holy Mass or the Sacraments celebrated in the forma ordinaria or against the Roman Pontiff as Supreme Pastor of the Universal Church.

Sacerdos idoneus (“Qualified Priest”) (cf. Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, art 5 § 4)

20. With respect to the question of the necessary requirements for a priest to be held idoneus (“qualified”) to celebrate in the forma extraordinaria, the following is hereby stated:

a. Every Catholic priest who is not impeded by Canon Law[7] is to be considered idoneus (“qualified”) for the celebration of the Holy Mass in the forma extraordinaria.

b. Regarding the use of the Latin language, a basic knowledge is necessary, allowing the priest to pronounce the words correctly and understand their meaning.

c. Regarding knowledge of the execution of the Rite, priests are presumed to be qualified who present themselves spontaneously to celebrate the forma extraordinaria, and have celebrated it previously.

21. Ordinaries are asked to offer their clergy the possibility of acquiring adequate preparation for celebrations in the forma extraordinaria. This applies also to Seminaries, where future priests should be given proper formation, including study of Latin[8] and, where pastoral needs suggest it, the opportunity to learn the forma extraordinaria of the Roman Rite.

22. In Dioceses without qualified priests, Diocesan Bishops can request assistance from priests of the Institutes erected by the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei, either to the celebrate the forma extraordinaria or to teach others how to celebrate it.

23. The faculty to celebrate sine populo (or with the participation of only one minister) in the forma extraordinaria of the Roman Rite is given by the Motu Proprio to all priests, whether secular or religious (cf. Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, art. 2). For such celebrations therefore, priests, by provision of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, do not require any special permission from their Ordinaries or superiors.

Liturgical and Ecclesiastical Discipline

24. The liturgical books of the forma extraordinaria are to be used as they are. All those who wish to celebrate according to the forma extraordinaria of the Roman Rite must know the pertinent rubrics and are obliged to follow them correctly.

25. New saints and certain of the new prefaces can and ought to be inserted into the 1962 Missal[9], according to provisions which will be indicated subsequently.

26. As foreseen by article 6 of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, the readings of the Holy Mass of the Missal of 1962 can be proclaimed either solely in the Latin language, or in Latin followed by the vernacular or, in Low Masses, solely in the vernacular.

27. With regard to the disciplinary norms connected to celebration, the ecclesiastical discipline contained in the Code of Canon Law of 1983 applies.

28. Furthermore, by virtue of its character of special law, within its own area, the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum derogates from those provisions of law, connected with the sacred Rites, promulgated from 1962 onwards and incompatible with the rubrics of the liturgical books in effect in 1962.

Confirmation and Holy Orders

29. Permission to use the older formula for the rite of Confirmation was confirmed by the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum (cf. art. 9 § 2). Therefore, in the forma extraordinaria, it is not necessary to use the newer formula of Pope Paul VI as found in the Ordo Confirmationis.

30. As regards tonsure, minor orders and the subdiaconate, the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum does not introduce any change in the discipline of the Code of Canon Law of 1983; consequently, in Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life which are under the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei, one who has made solemn profession or who has been definitively incorporated into a clerical institute of apostolic life, becomes incardinated as a cleric in the institute or society upon ordination to the diaconate, in accordance with canon 266 § 2 of the Code of Canon Law.

31. Only in Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life which are under the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei, and in those which use the liturgical books of the forma extraordinaria, is the use of the Pontificale Romanum of 1962 for the conferral of minor and major orders permitted.

Breviarium Romanum

32. Art. 9 § 3 of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum gives clerics the faculty to use the Breviarium Romanum in effect in 1962, which is to be prayed entirely and in the Latin language.

The Sacred Triduum

33. If there is a qualified priest, a coetus fidelium (“group of faithful”), which follows the older liturgical tradition, can also celebrate the Sacred Triduum in the forma extraordinaria. When there is no church or oratory designated exclusively for such celebrations, the parish priest or Ordinary, in agreement with the qualified priest, should find some arrangement favourable to the good of souls, not excluding the possibility of a repetition of the celebration of the Sacred Triduum in the same church.

The Rites of Religious Orders

34. The use of the liturgical books proper to the Religious Orders which were in effect in 1962 is permitted.

Pontificale Romanum and the Rituale Romanum

35. The use of the Pontificale Romanum, the Rituale Romanum, as well as the Caeremoniale Episcoporum in effect in 1962, is permitted, in keeping with n. 28 of this Instruction, and always respecting n. 31 of the same Instruction.

The Holy Father Pope Benedict XVI, in an audience granted to the undersigned Cardinal President of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei on 8 April 2011, approved this present Instruction and ordered its publication.

Given at Rome, at the Offices of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei, 30 April, 2011, on the memorial of Pope Saint Pius V.

William Cardinal LEVADA

President

Mons. Guido Pozzo

Secretary

[1] BENEDICTUS XVI, Litterae Apostolicae Summorum Pontificum motu proprio datae, I, AAS 99 (2007) 777; cf. Institutio Generalis Missalis Romani, tertia editio 2002, n. 397.

[2] BENEDICTUS XVI, Epistola ad Episcopos ad producendas Litteras Apostolicas motu proprio datas, de Usu Liturgiae Romanae Instaurationi anni 1970 praecedentis, AAS 99 (2007) 798.

[3] Cf. Code of Canon Law, Canon 838 §1 and §2.

[4] Cf. Code of Canon Law, Canon 331.

[5] Cf. Code of Canon Law, Canons 223 § 2 or 838 §1 and §4.

[6] BENEDICTUS XVI, Epistola ad Episcopos ad producendas Litteras Apostolicas motu proprio datas, de Usu Liturgiae Romanae Instaurationi anni 1970 praecedentis, AAS 99 (2007) 799.

[7] Cf. Code of Canon Law, Canon 900 § 2.

[8] Cf. Code of Canon Law, Canon 249; Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium, 36; Declaration Optatum totius, 13.

[9] BENEDICTUS XVI, Epistola ad Episcopos ad producendas Litteras Apostolicas motu proprio datas, de Usu Liturgiae Romanae Instaurationi anni 1970 praecedentis, AAS 99 (2007) 797.

May 20, 2011

The Parables of Christ, Part VI: Parable of the Wheat and Tares

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the May 2011 Newsletter

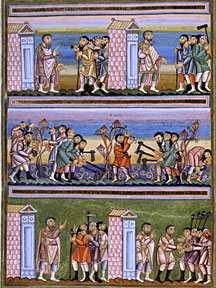

Our Lord introduces the parable of the wheat and the cockle by saying that “the kingdom of heaven is like a man who sowed good seed in his field.” The kingdom of heaven is the Church which Christ established for the salvation of all men and not only for the Jews. When in His explanation of the parable Our Lord identifies the field as the world, He is indicating the divine intention to save all men (cf. I Tim. 2:4). However, as Father Leopold Fonck, S.J. wrote: “But as unbelievers have rejected this kingdom, our divine Redeemer will regard the Faithful in their visible community which He himself founded as His special kingdom of Heaven, and it is in this more restricted sense that He applies the image in this parable” (Parables of the Gospel, p. 140).

This parable, as St. Thomas Aquinas observed, explains the origins of the good and the evil in the Church, their intermingling in this life and their final separation in the next. In the words of Monsignor Ronald Knox, it “is an answer to the question, ‘Do all Christians go to Heaven?’ And the answer is ‘No’.”

Just as in the parable, the wheat resulted from the good seed sown by the farmer and the cockle from what was sown over the wheat by his enemy, so Christ’s word brings into His Church those “who are born… of the will of God” but the devil through his blandishments seduces some in that Church from their allegiance to Christ.

The cockle in the parable was allowed to grow together with the wheat because uprooting it would certainly also destroy the wheat. Saint Thomas comments that the good can exist without the evil but the evil cannot exist without the good; therefore, he says, the Lord tolerates many who are evil so that the many who are good may not perish.

Furthermore, St. Thomas gives reasons why on account of the good members of the Church the evil ones should not be removed before the Judgment. One reason is that those who are evil provide the good with opportunities for the practice of virtue, especially that of patience. Secondly, it does happen that one who was once evil afterwards becomes good. If Saul who had persecuted the Church of God had been extirpated, the Church would not have had Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles. Thirdly, there are many who seem to be evil but are in reality good. If these were destroyed, the good would be destroyed.

In the parable the final separation of the wheat and the cockle takes place at the harvest; the wheat is placed in the farmer’s barn and the cockle bound “in bundles to burn.” In His explanation Our Lord says that at the end of the world the angels “shall gather out of his kingdom… them that work iniquity. And shall cast them into the furnace of fire…Then shall the just shine as the sun, in the kingdom of their Father” (cf. Matt. 13:39–43). The importance of this teaching cannot be overestimated for Catholics of our day who have heard from false teachers either that there is no hell or that no one goes there.

Indeed the final separation of the good and the evil who had been together in the Church is emphasized by its appearance in a companion parable found in the same thirteenth chapter of St. Matthew’s Gospel: “Again the kingdom of heaven is like to a net cast into the sea, and gathering together of all kind of fishes. Which when it was filled, they drew out, and sitting by the shore, they chose out the good into vessels but the bad they cast forth.

“So shall it be at the end of the world. The angels shall go out, and shall separate the wicked from the just” (Matt. 13:47–49).

These two parables force us to reflect on the words of St. Augustine who said that God, who made us without our willing it and who redeemed us without our willing it, will not save us unless we will it.

May 5, 2011

The Parables of Christ, Part V: Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the April 2011 Newsletter

The Gospel selected by the Church for Septuagesima Sunday is taken from Matthew 20:1–16, the parable of the workers in the vineyard. Since the season before Easter represents the time of trial and temptation of this passing world, this Gospel encourages us to labor manfully for the one thing necessary, the salvation of our souls.

In the parable a householder goes out five times in a single day to recruit workers for his vineyard. Only the group he meets the first time are hired for the agreed upon wage of a denarius. Those employed at the third, sixth and ninth hours are told that he will give them “what is just.” To those he finds at the eleventh hour he says, “Go you also into my vineyard. And when evening was come, the lord of the vineyard saith to his steward: call the laborers and pay them their hire, beginning from the last even to the first” (Matt. 20:7–8).

Seeing that those who worked only an hour were given a denarius, the ones employed first expected more but were bitterly disappointed when they also received a denarius. They complained against the master, “Saying: These last have worked but one hour and thou hast made them equal to us that have borne the burden of the day and the heats. But he answering said to one of them: Friend, I do thee no wrong: didst thou not agree with me for a denarius? Take what is thine, and go thy way: I will give to this last even as to thee. Or is it not lawful for me to do what I will?”

In paying those who came last a denarius for their labor, the owner of the vineyard displays his generosity. One commentator suggests, not without reason, that the householder was moved by kindness because he knew that the payment of anything less than a denarius, would not relieve the necessities of the laborer and his family.

What is the point of comparison between this image and the kingdom of heaven? It is suggested by the reaction of those who complained to the householder. They expected to receive more than the others because they had worked longer and endured more difficulties. By granting a denarius to those who worked a single hour, however, the householder shows that the work done is not the exclusive determinant.

So also in the kingdom of heaven, the Lord God, who sees the love which inspires men’s good works, even though these appeared insignificant in comparison to those of others, may reward equally those who worked a brief time with great love and those who worked a longer time with lesser love. “The decisive factor,” Father Leopold Fonck, S.J., observes “is the interior grace and co-operation on the part of man.”

We are not to conclude that there is no difference of degree among those who are saved, nor should we think that God rewards capriciously. He orders all things and judges all men most wisely. The point made in this parable is that those whom men, who can not see everything, judge to be first in the kingdom of heaven may be last and those, whom they consider last may be first. As God revealed to Samuel when the prophet thought Eliab would be the Lord’s anointed: “Man sees those things that appear, but the Lord beholds the heart” (I Kings 16:7).

Many things in this parable have their counterpart in the supernatural realm. The householder denotes Christ who will reward the just with the crown of eternal life. The time of the payment represents the general judgment when everyone will see the rewards and punishments given to others. The denarius signifies the eternal reward and the workers those who are saved.

The complaint of those paid last has no counterpart but is mentioned for the sake of the parable’s realism. In heaven all the just will rejoice over the happiness of others; envy will have no place.

Finally, a comment by Saint Augustine deserves mention. He says that those asked to go into the Lord’s vineyard early in the morning must not say: “Why should I tire myself out when I can go at the last hour and receive the same reward? When you are called, come. The reward promised is indeed the same but the great question concerns the hour of working. No one promised you that you will live until the eleventh hour. Take care lest what he by promising is prepared to give you, you by deferring

take away from yourself.”

April 5, 2011