Immanentism: Catholicism and Religious Experience, by D.Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

by Dr. Dennis Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

by Dr. Dennis Q. McInerny, Ph.D.

(Originally in the April 2011 Newsletter)

Immanentism? It is probably safe to say that many a good Catholic has never even heard of the term. Presuming that to be the case, a definition is in order. For that definition I call upon the eminent French theologian Father Louis Bouyer, who defines immanentism as follows: “A tendency to understand the immanence of God or of His action in us in such a way that it would, in fact, exclude the reality of His transcendence.” How is the immanence of God to be rightly understood? (By the way, the word “immanence” comes from the Latin verb immanere, meaning “to abide within.”) The immanence of God refers to the fact that He is present in a very special way in everyone who is in the state of sanctifying grace. One is reminded in this respect of Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity, who sought to structure her entire religious life around the sublime truth of the indwelling of the Blessed Trinity.

Immanence, then, is very much a good thing. Immanentism, on the other hand, is not at all a good thing, and that is because, by denying the transcendence of God, it of course utterly falsifies the divine nature. To deny the transcendence of God is to refuse to acknowledge the fact that He is absolutely distinct from and superior to His creatures, and the result of doing that is to end up with a knowledge which, whatever else may be said of it, is not knowledge of the one true God at all. Furthermore, to deny the transcendence of God is to undermine the rationale of immanentism itself, for “immanence” becomes meaningless if it refers to anything other than the transcendent God who dwells within us through His grace.

Father John Hardon, in writing on the subject of immanentist apologetics, refers to it as “A method of establishing the credibility of the Christian faith by appealing to the subjective satisfaction that the faith gives to the believer.” Coupled with this emphasis on the subjective, there is a downplaying of the objective criteria of our faith, even to the point of rejecting miracles and prophecies. Purely personal motives for faith, motives that have mainly to do with feelings, are given primary of place. “Religion, therefore, would consist,” Father Bouyer remarks, “entirely in the religious feeling itself.” Reason is marginalized, and the idea of belief, as being essentially the assent of the intellect, loses its currency.

Immanentism may be summed up by saying that it represents a stance of reckless subjectivism with regard to the faith. It cavalierly dismisses, as being of only secondary importance, the objective foundations of religion, as revealed to us by God Himself and as incorporated in the deposit of faith.

In 1907 Pope St. Pius X published his encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis, whose purpose was to sound the alarm against Modernism, which the Holy Father had defined as “the synthesis of all heresies.” And he described the Modernists themselves as “the most pernicious of all the adversaries of the Church.” In his analysis of the phenomenon, St. Pius X identified two major parts of Modernism; one was agnosticism, the other was immanentism. By agnosticism Modernism denies that man is capable of gaining a reasoned knowledge of God. Thus, with a stroke, it effectively does away with natural theology, that philosophic discipline whose principal task is to show that we can arrive at a knowledge of the existence of God through natural reason. Now, that such is possible is actually a matter of faith for Catholics, as was taught by the First Vatican Council.

Having disposed of natural theology, Modernism then proposes immanentism to explain what religious experience is supposedly all about. Human beings, the Modernists argue, are invested with a “religious sense” which wells up out of the unconscious and creates in us a need for the divine. It is in response to this need that we positively respond to ideas about the reality and nature of God which, as it happens, are comfortably conformable to our feelings. What this comes down to, in practical terms, is that the “God” to which one gives one’s allegiance is but a fiction of one’s own devising, a pseudo-being having its source nowhere else but in the demands of deep-set emotions. Here Modernism can be said to be reflecting the thought of the nineteenth century atheistic philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, who argued that what we call God is no more than the imagined product of human longings and wishes.

The kind of attitude which is represented by immanentism is very much a part of the religious consciousness of the age in which we live, and that is because Modernism, of which it is an integral part, is not, unfortunately, a thing of the past. Immanentism, carried to the extreme, is nothing more than a wholesale abandonment of the Christian faith, for which it substitutes a bland and anemic secularism vainly trying to disguise itself under a thin veneer of religion. Because immanentism places feelings above reason, it negates the objective reality of the faith as manifested in its doctrines, doctrines which have their source in divine revelation. To state the obvious, in contradistinction to immanentism, we give our assent to this or that doctrine of the faith because we believe it to be true, not because it is consonant with however we might feel about it.

In what way, specifically, could the spirit of immanentism be said to be present in the Church today? Generally, it would be in what we call “pick and choose Catholicism,” where individuals decide what they will and will not accept, as dictated by their feelings, not by reason. Feelings are fickle, but the right use of reason as applied to religious matters will never let us down, and that is because we know that there can be no conflict between faith and reason.

How many Catholics today treat the Church’s clear and unalterable teaching on contraception as if it were a minor matter that can be brushed aside with a whimsical wave of the hand? And surely there is a close connection between that attitude and the way in which, as the statistics make clear, a large number of Catholics view the institution of marriage today, looking at it in a way not much different from how our secular culture looks at it. Holy Matrimony would seem to have lost its holiness, and the vital necessity of recognizing marriage’s status as a sacrament, which means accepting its sanctity and permanence, is too often made difficult by the dominance of a befogging and self-serving legalism.

We are all immanentist to the extent that we deign to put our wills above the will of God, as that will has been clearly made known to us through revelation, and as that revelation is given concrete embodiment in the Church. To be seduced by immanentism is, at bottom, to make a pact with unreality, to succumb to subjectivism, to prefer “my way” over the right way, even though the mindless pursuit of “my way” involves setting out on a path which leads inevitably to my ultimate unravelment.

April 5, 2011

Diaconate Ordinations – March 2011

The Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter was blessed to have His Excellency, Czeslaw Kozon, Bishop of Copenhagen, Denmark, ordain five seminarians from Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary to the diaconate on March 19, 2011.

Those ordained were Gregory Eichman, Kevin O’Neill, Brian McDonnell, Karl Marsolle, and Kenneth Walker.

To view the full photo album, please visit the Seminary Archive here.

March 25, 2011

Camp St. Michael – 2011

The Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter is hosting an 11-day altar-boy training camp/RADIX Boot Camp for boys between the ages of 11 to 16 years, located at Camp Gargano. It will be staffed by one priest and six seminarians from the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, along with Mr. Doug Barry (founder of RADIX) and his staff. This unique opportunity will provide campers with the mass-serving expertise of the seminarians and Mr. Barry’s professionally developed RADIX programs.

COST: The cost for this year’s camp is $350, payable by check, which should be sent along with the application form. (This check will only be deposited if your applicant is accepted.)

Director, Camp St. Michael

PO Box 147

Denton, NE 68339

For further information, please contact the Camp Director at:

campstmichael@olgseminary.com

(402) 797-7700

If you would like to know more about Doug Barry and RADIX, please visit his website at: http://www.radixguys.com/

For more information, please visit our Summer Camp Website

March 18, 2011

Camp St. Isaac Jogues – 2011

Camp St. Isaac Jogues, centered on the Mass, challenges boys to practice fortitude and prudence by daily catechism, sports, and hiking. It is staffed by seminarians of Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary and a priest of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter. Boys 13 to 15 years old may apply.

The cost per boy is $350.00, payable to Camp St. Isaac Jogues. Please send with completed medical/parental release (click here for form) to:

Camp St. Isaac Jogues,

Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary,

PO Box 147,

Denton, NE 68339.

The Camp is held at St. Gregory’s Academy in Elmhurst, PA. Its length is 10 days, beginning at 2 pm on Wednesday, July 13th and ending at 2pm on Saturday, July 23rd.

For more information, please visit our Summer Camp website.

Camp St. Peter – 2011

The Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter is hosting a two-week, outdoor summer camp for boys aged 13 to 15 years old, at Custer State Park, located an hour south of Rapid City, South Dakota. The camp will be staffed by one priest and six seminarians from the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter.

COST: The cost for this years camp is $350, payable by check, which should be sent along with the application form. This check will only be deposited if your applicant is accepted. (Please send a separate check for each applicant.)

DATES: July 18 – 29th, 2011

For More Information, please visit our Summer Camp website.

Subdiaconate and Tonsure – January 2011

On January 29th of this year, the His Excellency Fabian Bruskewitz of Lincoln conferred the tonsure and subdiaconate upon several men at Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary in Denton, Nebraska. Please view our photo gallery of the liturgy from the seminary’s website.

March 8, 2011

The Parables of Christ, Part IV: Parable of the Unjust Steward

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James B. Buckley, FSSP

From the March 2011 Newsletter

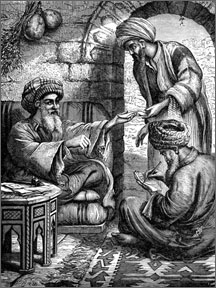

The Gospel for the eighth Sunday after Pentecost is taken from Saint Luke 16:1-9 and contains the parable of the Unjust Steward: (1) “And He said also to his disciples: There was a certain rich man who had a steward: and this man was accused unto him, that he was wasting his goods. (2) And he called him, and said to him: What is this I hear of you? Give an account of your stewardship: for now you can be steward no longer. (3) And the steward said within himself: What shall I do, since my lord is taking from me my stewardship? To dig I am not able; to beg I am ashamed. (4) I know what I will do, that when I am removed from my stewardship they may receive me into their houses. (5) Calling therefore together every one of his lord’s debtors, he said to the first: How much do you owe my lord? (6) But he said: A hundred barrels of oil. And he said to him: Take your bond and sit down quickly and write fifty. (7) Then he said to another: And how much do you owe? And he said a hundred quarters of wheat. He said to him: Take your bond and write eighty. (8) And the lord commended the unjust steward forasmuch as he had done wisely: for the children of this world are wiser in their own generation than the children of light. (9) And I say to you: Make for yourselves friends of the mammon of iniquity; that when it comes to an end, they may receive you into everlasting dwellings.”

The chief difficulty the modern reader finds with the realism of this parable is that the steward after being told of his dismissal is still allowed to exercise his office. Father Leopold Fonck, S.J., a great scriptural scholar, maintains, however, that in Palestine during Our Lord’s public ministry some time would elapse before a discharged steward would surrender his office to a successor.

A more serious difficulty, Fonck observes, concerns the debtors’ bonds which, he surmises, represent the rents on the tenants’ farms. He writes: “For, if the steward, as was usual amongst Oriental officials, in previous years had exacted from the farmers or with their aid, from the peasants, much larger sums of money than he transmitted to his master, he, now, without resorting to any very clumsy or conspicuous fraud upon his master, could make a considerable reduction in the charges of the peasants.” On this supposition it is not difficult to see why the unjust steward expected to be rewarded by the tenant farmers after his master dismissed him.

The master praises the unjust steward not for his dishonesty but for his sagacity. Using the remaining time of his employment with cunning, he was able to provide for his future.

To discover this parable’s meaning one can follow the advice of Tertullian who wrote that one will find no parable which was not either explained by Christ or illumined by a commentary of an evangelist. “For the children of this world are wiser in their own generation than the children of light” is a comment emphasizing the necessity of prudence. The unjust steward represents the “children of this world” because he lives his life estranged from God. He, however, acts more wisely to secure his temporal good in this passing world than do those enlightened by the truth of Christ to attain their eternal good. Since prudence is the virtue which directs man’s actions to their goal, Christ is exhorting His disciples not to be outdone by the cunning of the wicked but to pursue those virtuous acts which will lead to their everlasting happiness.

Money is called the mammon of iniquity because it can be gained by sinful means and used for sinful purposes. The implication of verse 9 is that Christ’s faithful should use their legitimate wealth to aid the needy. By so doing they will exercise prudence because these virtuous actions are the means to the eternal life of heaven where Christ and all His saints will receive them in everlasting mansions. This detail contrasts sharply with the knavery of the unjust steward who used sinful means to be received by his beneficiaries into earthly dwellings which will pass away.

March 5, 2011

Feast of the Chair of St. Peter

This year the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter was honored to begin celebrating February 22nd, the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter, as a first class feast as was recently granted by the Holy See.

Below are photos taken from the Solemn High Mass celebrated for the occasion at the North American District Headquarters. Fr. Simon Harkins, FSSP was the celebrant, with Fr. Justin Nolan, FSSP as deacon and Mr. Gregory Bartholomew, FSSP as subdeacon. Boys from St. Gregory’s Academy served Mass and provided the schola cantorum.

Photos courtesy of Joseph Dalimata.

February 23, 2011

Mortification in Lent, a Lenten Reflection for 2011

During the holy season of Lent, Holy Mother Church encourages us to spend forty days growing in knowledge of ourselves, so that, by our penance, we may better understand the exalted value of the soul over the body. By means of prayer, fasting, and almsgiving, the desires of the body are placed in subjection to the higher faculties of the intellect and will: By prayer we elevate our minds to God, by fasting we lessen our desire for pleasure, and by almsgiving we curb our love of money.

During the holy season of Lent, Holy Mother Church encourages us to spend forty days growing in knowledge of ourselves, so that, by our penance, we may better understand the exalted value of the soul over the body. By means of prayer, fasting, and almsgiving, the desires of the body are placed in subjection to the higher faculties of the intellect and will: By prayer we elevate our minds to God, by fasting we lessen our desire for pleasure, and by almsgiving we curb our love of money.

By fasting forty days in the desert, Our Lord, too, showed that there are benefits of denying the senses and appetites what is morally permitted them. Furthermore, the saints have testified that the detachment from creation (possessions, people, enjoyments) is absolutely necessary to arrive at perfection, for it is typical that God completes the purification of the soul only after it has expended great time and effort doing so by ordinary means. Thus, it is our obligation to mortify our senses and passions so that the soul’s capacity for her Creator is not otherwise occupied with His creation.

It should be noted that “to mortify” does not mean that we annihilate our senses, appetites, or passions; rather, we practice self-denial or privation in order to orient all desires and appetites towards God and make Him the sole desire (object) of our heart, mind, body, and soul.

Besides the senses and appetites of the body, the higher faculties of the intellect and will must also be purified. The intellect apprehends the true and presents it to the will as a good thing to pursue out of love. Thus, the action of the will is to love what the intellect says is good. But since the fall of Adam, the intellect has been darkened and the will has been weakened to the point where the will is inclined to selfishness and seeks to love that which the intellect can erroneously perceive as a good.

The superiority of the soul over the body means that the mortification of the will—the rational appetite—is even more important than the mortification of the body.

Contrarily, when the will embraces that which it should not, this turning away from God and towards creation is called sin. As sin resides in the will, it is the home of our faults and needs to be purified in order to regain strength to love purely the One Who is All-good, God.

When the free will is not properly ordered, the person lives for himself, seeking his own gratification in this world. Excessive self-centeredness subdues the soul so that sufferings and hardships are not willingly endured; fraternal correction and advice are not heeded; and pride, disobedience, and impatience develop deep roots in the soul. This inordinate self-love causes the person to abhor mortification. To express it in scientific terms, the person thinks that the world is not geocentric or heliocentric, but rather egocentric.

Hence, it is extremely important to mortify the will to combat pride and to lessen excessive love of self. Ultimately, the more the intellect understands the baseness of anything temporal (for example, the body) compared with the importance of the eternal (our soul, God), the greater the will turns to God in love. For it is only in her humility that the soul recognizes that without God, she is nothing.

As Lent is upon us, the resolution to maintain a stricter guard over our appetites ensures that the intellect and will are properly maintained as the sovereign faculties. In closely examining the giving up of some food, we recognize that there will be a corresponding suffering in the body. The growth in sanctification from this mortification is not so much in the pain itself; rather, it is in the intention of the will to embrace the suffering out of love for God. And such is the power of love (charity): it takes a finite act and produces an infinite value. Hence, in all that we do in daily life, if borne out of love for God or in union with Christ Crucified, the action produces a hundred-fold merit, based upon the charity God sees in our intention. This is why the

widow who gave two mites gave more than all others: it is because she gave out of charity.

But great pain can reside in the will, more so than pain in the body. If a person were to hit us, the physical pain may subside in a few minutes, but deep down inside, the will can hold onto the emotional or intellectual pain. At times, the mind can take this memory and actually increase the suffering so that by recalling the incident, the person increases his pain. If that pain continues to grow in one’s mind or heart, and the will decides to remain offended instead of forgiving, then the mental, emotional, or spiritual health of that person is at risk.

We witness this phenomenon in the Western world: The notion of “I do what I want” is so prevalent that when we have to do something or endure something which we do not want to do, we feel violated or helpless. Such feelings, if not dealt with properly, remove joy from a soul, replace it with anger, bitterness, and even hatred towards other people—or even God. Ultimately, a society which overly emphasizes doing one’s will produces a culture which abhors authority, whether parental, governmental, or ecclesiastical.

For how dare another tell me what I should do? “I have my own will.” This rebellion to get our own way is readily seen in most children in their first years of life. When a child does not get his way, he throws a tantrum. Thus, it is incumbent upon parents to admonish, teach, and lead by example that there are many times in life when we have to do things which we prefer not to do. By such instruction, children will grow up to better respect proper authority, such as their parents and the Church, and thereby to use their will properly to choose good and avoid evil.

Because we live in a world where temptations abound, we are further required continually to monitor our will, chastise it when disordered, and re-direct it to the good when it fails. As this requires mortification, we annually employ the Lenten days of penance to maintain the will within its proper boundaries.

Furthermore, a pure motive for our penitential practices is also necessary for perfect union with God. Penance can be performed for less noble purposes, such as to lose weight or to seek the praise of others, or out of some Stoic attitude that emotions are beneath us. Yet, penance is more meritorious if done for the greater glory of God, or to conform our will to His Divine Will, or to strengthen the will over the senses, appetites, and passions of the body. The renewal of our pure motive will most likely have to be done throughout Lent in order to persevere in our good intention.

Lent is a time of not seeking or wishing anything other than to follow Christ Crucified and to give honor and glory to His Name, for the salvation of souls. So let us follow the advice of St. John of the Cross: “In order to arrive at having pleasure in everything, desire to have pleasure in nothing.”

February 8, 2011

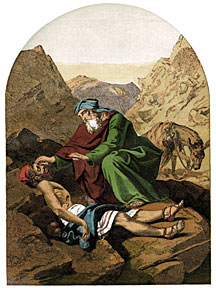

The Parables of Christ, Part III: Parable of the Good Samaritan

by Fr. James Buckley, FSSP

by Fr. James Buckley, FSSP

From the February 2011 Fraternity Newsletter

Since a parable manifests a truth of the supernatural order by comparing it to some image from nature or the life of man, it is all important to discover the point of comparison between the two. As Saint Basil the great observed, “The parables do not correspond to the exterior image in all its parts of the subject to be considered but direct the attention to the principal truth.” Nevertheless, that basic comparison, as Our Lord’s own explanations of some parables demonstrate, can be extended to different parts of the parable.

A great clue to understanding the point of comparison will be found in the words introducing or concluding the parable. The parable of the Good Samaritan, for example, was introduced by a lawyer’s question, i.e., “And who is my neighbor?” It answers the question by providing a concrete image and not by offering a philosophical definition. At its conclusion, Our Lord emphasizes its point when He asks, “Which of these three, in thy opinion, was neighbor to him that fell among the robbers?” (Luke 10:36)

Similarly, Our Lord first admonished His hearers “to pray and not to faint” before presenting to them the parable of the unjust judge. In a few lines He tells how the sheer persistence of the widow forced one who feared neither God nor man to grant her justice. His concluding remark makes the supernatural truth obvious, i.e., “And will not God revenge his elect who cry to him day and night and will he have patience in their regard? I say to you, that he will quickly revenge them.” (Luke 18:7–8)

Though the parable of the two sons has no introduction, it has a significant conclusion. Our Lord tells His audience that when a father asked his two sons to work in his vineyard, the first one said that he would not but the second said that he would. The one who agreed to work did not, but the one who refused to work repented and worked. When Our Lord asked them which did his father’s will, they replied “the first.” Christ reveals the comparison in the conclusion: “Amen I say to you, that the publicans and the harlots shall go into the kingdom of God before you. For John came to you in the way of justice and you did not believe him. But the publicans and the harlots believed him: but you, seeing it did not afterwards repent, that you might believe.” (Matt. 21:32)

It is the conclusion of the parable of the ten virgins which also indicates the comparison (i.e., “Watch ye therefore, because you know not the day or the hour” [Matt. 25:13]). In this parable the foolish virgins, by neglecting to take oil with their lamps, failed to welcome the bridegroom at his arrival and, consequently, merited the punishment of not participating in the wedding feast. The comparison is this. Just as the virgins were obliged to have their lamps burning when the bridegroom arrived, so too the faithful are obliged to prepare for Christ’s coming in judgment by their good works. Those who do will enter into everlasting life, but those who do not will be condemned by those dreadful words, i.e., “Amen I say to you, I know you not.”

It is the conclusion of the parable of the ten virgins which also indicates the comparison (i.e., “Watch ye therefore, because you know not the day or the hour” [Matt. 25:13]). In this parable the foolish virgins, by neglecting to take oil with their lamps, failed to welcome the bridegroom at his arrival and, consequently, merited the punishment of not participating in the wedding feast. The comparison is this. Just as the virgins were obliged to have their lamps burning when the bridegroom arrived, so too the faithful are obliged to prepare for Christ’s coming in judgment by their good works. Those who do will enter into everlasting life, but those who do not will be condemned by those dreadful words, i.e., “Amen I say to you, I know you not.”

This central comparison is extended to other parts of the image. The bridegroom who bars the foolish virgins from the wedding feast is Christ who will reward each man according to his deeds. The wedding feast, therefore, represents the everlasting happiness of heaven. The uncertainty regarding the time of the bridegroom’s arrival signifies that the time of Christ’s second coming is hidden from us. There are many other incidents in the parable which have no supernatural counterpart. It is of no significance, for example, that while the bridegroom tarried all the virgins slept. This is merely a detail enhancing the realism of Christ’s story. The same is true of the refusal of the wise virgins to share their oil with the foolish.

Next time I will look at the parable of the unjust steward.

February 5, 2011