“Ad Orientem”: Why is the Mass Celebrated Facing East?

by Fr. Hubert Bizard, FSSP

French original at claves.org.

Translated by Anastasiia Cherygova.

On one hand, the question of the priest’s orientation towards the altar is connected to another greater question of liturgical symbolism. On the other hand, it is connected to a more specific question of the orientation of prayer.

When it comes to liturgical symbolism, we should understand, first and foremost, that the gestures and attitudes in public prayer are never meaningless nor left to the private opinion of the celebrant (1).

The orientation of the priest at the altar is a part of the rites determined by the Church; this orientation is a part of an even more ancient orientation of prayer.

Orientation in Prayer

The phenomenon of orientation in prayer existed already in the Old Testament, when Jews would ordinarily pray facing the temple in Jerusalem, “where God resided”; also, thirty passages of the Old Testament demonstrate the practice of praying facing East. (2)

In the early Church, when liturgical symbolism was very important, turning East for liturgical prayer would very quickly become the common practice – thence comes the word itself “orientation”, from Latin orient, East. This practice would be so deeply entrenched that during a considerable period of time, starting from the 5th century, churches would be almost systematically built with their sanctuaries facing East. There is an abundance of contemporary witnesses to attest and justify this orientation of places of worship. (3)

Cardinal Bona, a great liturgist, wrote in the 18th century:

“From [looking] at the historic monuments, we may conclude that churches, in both the Greek and Latin Churches, were built in such a way that they were directed towards sunrise during the time of an equinox. This custom was formerly so strictly followed by the monks of the Cistercian Order that not only would their high altar be turned East, but all the other altars would be turned in the same direction.” (4)

This practice, however, was not completely universal. For instance, older Roman basilicas were “westernized” – this is why the priest and the faithful, for certain parts of the Mass when it comes to the latter, would turn to the doors in order that their prayer would still remain “oriented” – facing East.

“The Orient is his name”

Why turn to the East? Because it represents Christ according to the designation given by the prophet Zacharias (6:12): “Behold a Man, the Orient is his name.” He is again oriens ex alto (Luke 1:78). This is also where one of the Advent antiphons comes from: “Oh Orient, splendor of eternal light and the sun of justice, come and enlighten those who…”

Turning East then simply meant turning oneself to God. Some baptismal liturgies would prescribe even to the baptized neophytes to spit in the direction of the West, signifying renouncing Satan, before turning East to profess their faith and adhere to God. (5)

Turning East is also turning towards the direction of the rising sun, and, according to the prophesy of the prophet Malachi (4:2), Christ would be called “sun of justice”, sol justitiæ.

Moreover, with Christ having risen to the East during His Ascension, as per the prophesy of Psalm 67 (7), the East was also the same place whence His return was also expected. The “oriented”, East-facing prayer thus possessed also an eschatological dimension. (8)

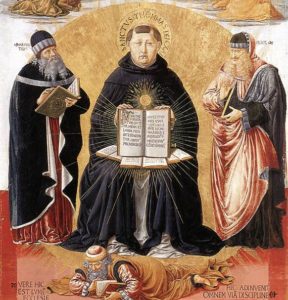

Saint Thomas Aquinas himself in the Summa Theologiæ writes on the different motives of the orientation of prayer, adding to the discussion a common idea of the location of the Earthly Paradise being in the East:

“It is for reasons of propriety that we adore facing East. It is most especially because of the divine majesty that the East symbolizes, where the movement of heaven has its origin. Afterwards, it is there where the Earthly Paradise was established according to the text of the Septuagint (Genesis 2:8): we appear therefore to want to return there. Lastly, it is because of Christ, the light of the world who carries the name of Orient (Zacharias 6:12) and who “has risen above all the heavens in the East” (Psalm 78:34), whence we await His supreme return, according to Saint Matthew (Matthew 24:27): “As the lightning goes from the East and shines until the West, like this would be the return of the Son of Man. (9)”

And Today?

Even if it may be that, for generally practical reasons, through the centuries the orientation of the churches to the literal East had fallen into disuse, the direction of the minister and of the faithful would not. Together, they would be turned in the same direction, that of the cross, always present above or behind the altar. This is to say that they would still be facing God, the essential of the orientation being preserved.

To celebrate the Mass “with his back to the people” as it is said today sometimes, was never perceived as a way for the priest to turn his back towards the faithful, but rather and above all to turn with them to the Lord, since it is to Him that our prayers and our chants are addressed. It is to Him also that the sacrifice is offered.

If the celebration of the Mass today, according to the new liturgical books is done almost universally towards the people, let us make a note that the so-called Missal of Paul VI does not demand the celebration facing the congregation. Moreover, the Conciliar Constitution of the Second Vatican Council, according to which the Mass was reformed, did not once address the question of the position of the celebrant at the altar or demanded any changes in this matter.

References:

- Human nature is such that it is difficult for it to rise to the meditation of Divine things without the aid of supporting exterior aid. This is why the Church, as a pious mother, has instituted the rites, in virtue of which some formulas during the Mass would be pronounced silently, while others would be pronounced audibly. Similarly, instructed by the apostles and the tradition, she has established ceremonies, mysterious blessings, lamps, incensings, ornaments and many things of such usage meant to remind the majesty of such great a sacrifice, as well as to excite the spirit of the faithful to raise themselves through these exterior signs of religion and of piety to the contemplation of the very sublime things hidden in this sacrifice. (Council of Trent, 22nd session, chap. 5).

- Dom Gaspar Lefebvre, Manuel de liturgie, Ed. Apostolat liturgique, Bruges, 1934, p. 182. (tr. Manual of the Liturgy)

- According to the Apostolic Constitutions of the 4th century, it was ordained that the churches would be “elongated in the shape of a vessel and turned towards the East” (Les constitutions apostoliques, Ed. du Cerf, 1992, p. 112). Even earlier than that, Tertullian would write: “the house of our dove is simple, and [it is] turned to the light. The image of the Holy Spirit loves the east. It is towards the Eastern region that we pray.” (Adv. Val., c.3.) Saint Isidore of Seville would report centuries later that “when the ancients would build a temple, they would turn themselves facing the East of the equinox, in order that the one who would be in prayers would be turned to the real East” (Origines L. XV) The celebrant priest in the morning would see the sunlight illuminate him through the stained-glass windows.

- Migne, Dictionnaire d’archéologie sacrée, t. II, 1204 (tr. Dictionary of Sacred Archeology)

- When we rise to pray, we turn ourselves towards the East, there where the sun rises. It is not that God would be there, having abandoned other regions of the world… but rather to exhort the mind to raise itself towards a superior place, that is to say to God. (Saint Augustine, P.L. XXXIV, col 1277)

- Just as the East is the image of birth, it is also a figure symbolizing truth triumphing over error. Therefore we, Christians, have a habit of turning towards East when we pray. This is no longer like with the pagans, to adore the sun, but to adore the sun of justice and of truth. (Saint Clement of Alexandria in Dom Gaspard Lefebvre, Manuel de liturgie, Ed. Apostolat liturgique, Bruges, 1934, p. 183).

- Celebrate the Lord who rises to the highest heaven to the East.

- During the Ascension, He rose to the East, and it is in this direction that the apostles adored Him, and it is just like that that He will return, as they have seen Him ascend to Heaven, as He himself said the Lord: “as the lightning goes from the East is immediately in the West, the same would be the return of the Son of Man.” Since we are waiting for Him, we also pray towards the East. It is an unwritten tradition of the apostles. (Saint John Damascene, Orthod. Fidei., 1. IV, c. 13).

- Secunda Secundæ, q. 84, a.3 ad 3um (Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiæ)

January 18, 2023

Exemplaric Baptism

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

The word “Epiphany” comes from the Greek “ἐπιφάνεια,” [epipháneia] which means “manifestation,” and the Feast of the Epiphany, kept on January 6th, the 13th Day of Christmas, commemorates three manifestations of Christ: the visitation of the Magi from the East, Our Lord’s Baptism, and Our Lord’s first miracle of turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana. While all three are interwoven in the Office for the Epiphany, the Mass of Epiphany day itself focuses on the visitation of the Magi. The Baptism of the Lord is celebrated in the Mass on January 13th, the Octave Day of the Epiphany, while the Miracle at Cana is commemorated on the Second Sunday after the Epiphany.

The recounting of Our Lord’s Baptism, in addition to presenting an important event in Our Lord’s life, also has meaning for the Faithful. This is because Our Lord’s Baptism is the exemplar, the model, of the Baptism received by the Faithful (S.T. III, q. 39, a. 5, c). What is expressed in the text of Sacred Scripture as occurring at Our Lord’s Baptism gives insight into what happens when the Sacrament of Baptism is conferred. Following St. Thomas Aquinas, the different aspects of Our Lord’s Baptism will be examined.

When Jesus was Baptized, the voice of the Father was heard saying “Thou art my beloved Son. In thee I am well pleased” (Luk 3:22, Mat 3:17, Mar 1:11). This indicates that the Faithful become, through Baptism, adopted sons of God, for as this was said to Christ, it is said also to each at their Baptism. As St. Hilary said, “the Father’s voice declares us to have become the adopted sons of God” (S.T. III, q. 39, a. 8, ad. 3).

St. Luke relates in his account of Our Lord’s Baptism “that Jesus also being baptized and praying, heaven was opened” (Luk 3:21; see also Mat 3:16, Mar 1:10). St. Thomas explains that this occurred for several reasons, which he explains as follows (S.T. III, q. 39, a. 5, c):

Christ wished to be baptized in order to consecrate the baptism wherewith we were to be baptized. And therefore it behooved those things to be shown forth which belong to the efficacy of our baptism: concerning which efficacy three points are to be considered. First, the principal power from which it is derived; and this, indeed, is a heavenly power. For which reason, when Christ was baptized, heaven was opened, to show that in future the heavenly power would sanctify baptism.

Secondly, the faith of the Church and of the person baptized conduces to the efficacy of baptism: wherefore those who are baptized make a profession of faith, and baptism is called the “sacrament of faith.” Now by faith we gaze on heavenly things, which surpass the senses and human reason. And in order to signify this, the heavens were opened when Christ was baptized.

Thirdly, because the entrance to the heavenly kingdom was opened to us by the baptism of Christ in a special manner, which entrance had been closed to the first man through sin. Hence, when Christ was baptized, the heavens were opened, to show that the way to heaven is open to the baptized.

Now after baptism man needs to pray continually, in order to enter heaven: for though sins are remitted through baptism, there still remain the fomes of sin [“an inclination of the sensual appetite to what is contrary to reason” (S.T. III, q. 15, a. 2, c)] assailing us from within, and the world and the devils assailing us from without. And therefore it is said pointedly (Luke 3:21) that “Jesus being baptized and praying, heaven was opened”: because, to wit, the faithful after baptism stand in need of prayer. Or else, that we may be led to understand that the very fact that through baptism heaven is opened to believers is in virtue of the prayer of Christ. Hence it is said pointedly (Matthew 3:16) that “heaven was opened to Him”—that is, “to all for His sake.” Thus, for example, the Emperor might say to one asking a favor for another: “Behold, I grant this favor, not to him, but to thee”—that is, “to him for thy sake,” as Chrysostom says (Hom. iv in Matth. [From the supposititious Opus Imperfectum]).

So it is that “heaven was opened” to express that the source of the power of Baptism is a heavenly source; that Baptism is the Sacrament of Faith and that by Faith the Faithful gaze on heavenly things, which surpass the senses and human reason; that the Kingdom of Heaven which was closed to the faithful by sin, is open to them by Baptism; and, that after Baptism, a man must pray in order to enter heaven for, although the way is open, he can only arrive there by prayer.

Lastly, it is reported that “the Holy Ghost descended in a bodily shape, as a dove” (Luk 3:22; see also Mat 3:16, Mar 1:10). According to St. Thomas, it was fitting that the Holy Ghost should appear in the form of a dove for four reasons (S.T. III, q. 39, a. 6, ad. 4):

First, on account of the disposition required in the one baptized—namely, that he approach in good faith: since as it is written (Wisdom 1:5): “The holy spirit of discipline will flee from the deceitful.” For the dove is an animal of a simple character, void of cunning and deceit: whence it is said (Matthew 10:16): “Be ye simple as doves.”

Secondly, in order to designate the seven gifts of the Holy Ghost, which are signified by the properties of the dove. For the dove dwells beside the running stream, in order that, on perceiving the hawk, it may plunge in and escape. This refers to the gift of wisdom, whereby the saints dwell beside the running waters of Holy Scripture, in order to escape the assaults of the devil. Again, the dove prefers the more choice seeds. This refers to the gift of knowledge, whereby the saints make choice of sound doctrines, with which they nourish themselves. Further, the dove feeds the brood of other birds. This refers to the gift of counsel, with which the saints, by teaching and example, feed men who have been the brood, i.e. imitators, of the devil. Again, the dove tears not with its beak. This refers to the gift of understanding, wherewith the saints do not rend sound doctrines, as heretics do. Again, the dove has no gall. This refers to the gift of piety, by reason of which the saints are free from unreasonable anger. Again, the dove builds its nest in the cleft of a rock. This refers to the gift of fortitude, wherewith the saints build their nest, i.e. take refuge and hope, in the death wounds of Christ, who is the Rock of strength. Lastly, the dove has a plaintive song. This refers to the gift of fear, wherewith the saints delight in bewailing sins.

Thirdly, the Holy Ghost appeared under the form of a dove on account of the proper effect of baptism, which is the remission of sins and reconciliation with God: for the dove is a gentle creature. Wherefore, as Chrysostom says, (Hom. xii in Matth.), “at the Deluge this creature appeared bearing an olive branch, and publishing the tidings of the universal peace of the whole world: and now again the dove appears at the baptism, pointing to our Deliverer.”

Fourthly, the Holy Ghost appeared over our Lord at His baptism in the form of a dove, in order to designate the common effect of baptism—namely, the building up of the unity of the Church. Hence it is written (Ephesians 5:25-27): “Christ delivered Himself up…that He might present…to Himself a glorious Church, not having spot or wrinkle, or any such thing…cleansing it by the laver of water in the word of life.” Therefore it was fitting that the Holy Ghost should appear at the baptism under the form of a dove, which is a creature both loving and gregarious. Wherefore also it is said of the Church (Canticles 6:8): “One is my dove.”

It is fitting, therefore, that the Holy Ghost appeared as a dove, for the dove signified the disposition one should have when receiving Baptism; the Gifts of the Holy Ghost which are first received in Baptism; the forgiveness of sins and reconciliation with God, and, lastly, the building up of the Mystical Body of Christ, the Church.

With the example of Our Lord’s Baptism presented on this day, and the explanation given by St. Thomas, the Faithful are invited to treasure as most precious what they have received in their Baptism, to give thanks to God for this great benefit He has freely bestowed, and to ponder these great mysteries in their hearts.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

January 13, 2023

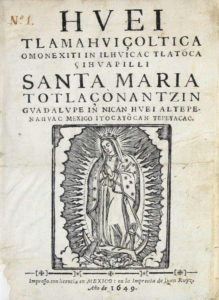

Serenade to Our Lady of Guadalupe

Every nation has shown its love for the Mother of God in different ways: offering flowers, devotions, rosaries etc. But, Mexicans have developed a very peculiar way of expressing their love for the Mother of God, the serenade to the Guadalupana. Mexicans as a people like to sing, and it has always been a traditional custom to serenade loved ones, be it the mother, the wife, and…why not?…the Blessed Virgin of Guadalupe, Queen and Mother of the Mexican people.

The origin and the date on which this tradition began is unknown, but there are records of non-liturgical songs that the indigenous people of Mexico sang to Our Lady of Guadalupe when they visited her house on hill of Tepeyac. Some of these songs dating from the 16th century were rediscovered by the San Antonio Vocal Arts Ensemble on their album “Guadalupe Virgen de los indios”, and they are a sign of the affection that was already felt for our Lady. Over the years it became customary to sing to our Lady of Guadalupe when she was visited at Tepeyac, but this custom was only in her Basilica in Mexico City where faithful and artists arrived on December 12 to honor her.

The origin and the date on which this tradition began is unknown, but there are records of non-liturgical songs that the indigenous people of Mexico sang to Our Lady of Guadalupe when they visited her house on hill of Tepeyac. Some of these songs dating from the 16th century were rediscovered by the San Antonio Vocal Arts Ensemble on their album “Guadalupe Virgen de los indios”, and they are a sign of the affection that was already felt for our Lady. Over the years it became customary to sing to our Lady of Guadalupe when she was visited at Tepeyac, but this custom was only in her Basilica in Mexico City where faithful and artists arrived on December 12 to honor her.

In 1932, the first live transmission of the mañanitas was made on the radio and in a more organized way. A microphone was placed at the entrance of the Basilica from where our Lady was serenaded, and it is at this point where the tradition began to extend to other parts of Mexico. The radio broadcasts were interrupted for some years and then resumed by Mr. Carlos Salinas Saucedo, who was the producer who started Las Mañanitas a la Virgen de Guadalupe on television live from the Basilica of Guadalupe and did so for 45 years from 1951 to 1997. With the first television transmission of the Mañanitas to the Guadalupana live from the Basilica of Guadalupe, this beautiful tradition spread throughout Mexico and the world.

At the Seminary of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the feast of December 12 has always been a special day celebrated with solemnity. In 2012, this longstanding Mexican tradition was added to the communal celebrations when a group of seminarians approached Father Joseph Bisig, rector of the seminary, to request permission to decorate the altar of our Lady of Guadalupe for the feast and to be able to serenade her on December 11 at night.

That first year the serenade was a complete success. Seminarians went around collecting donations and the altar was able to be decorated with many roses and candles. Seminarians sang to our Lady in various languages, thus demonstrating the internationality of the Fraternity’s seminary. The following year, due to the success of the first serenade, Father Bisig gave permission for the serenade to be extended until midnight to receive December 12 singing to the Virgin of Guadalupe the traditional Mañanitas Tapatías.

This was the humble beginning of this beautiful tradition to the Guadalupana in our seminary. Over the years the decorations have become more elaborate, and the tradition has become so dear and expected by our seminarians because with it they join the millions of Christians around the world who every December 11 express their love for the Morenita del Tepeyac, serenading her with hymns of praise and love.

This was the humble beginning of this beautiful tradition to the Guadalupana in our seminary. Over the years the decorations have become more elaborate, and the tradition has become so dear and expected by our seminarians because with it they join the millions of Christians around the world who every December 11 express their love for the Morenita del Tepeyac, serenading her with hymns of praise and love.

January 10, 2023

Death of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI

Fribourg, December 31, 2022

It is with sorrow that the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter learned today, December 31, 2022, of the death of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, who was on several occasions a providential support for our community. As Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, he was instrumental in the founding of the Fraternity and even visited its seminary in Wigratzbad for Holy Week in 1990. After his election to the chair of Peter, the personal contact continued, especially with the private audience he granted to his founders and the Superior General on July 6, 2009: it was for us the occasion to thank him for the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum. A few months ago, from his place of retirement at the Mater Ecclesiæ monastery in the Vatican, he sent a private letter of encouragement to the Superior of the Fraternity of Saint Peter following the Motu Proprio Traditiones Custodes. The priests of the Fraternity, together with the faithful who are close to it, will be ardently praying for the repose of his soul. Requiem Masses with the absolution will be celebrated in the apostolates entrusted to the Fraternity in order to “pray to God that through the Sacrifice offered for the soul of his servant, the Sovereign Pontiff Benedict XVI, and after having raised him in this world to the papal office, he may be admitted into the celestial kingdom in the company of all the saints.” (secret of the Requiem Mass for a Sovereign Pontiff)

Source: www.fssp.org

December 31, 2022

Benjaminite Comites

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

The three Feasts following Christmas – St. Stephen, St. John the Apostle, and the Holy Innocents – are known as the Comites Christi, that is, the “Companions of Christ,” as they are the first Saints on the liturgical calendar to attend, as it were, to the newborn Christ Child. These three feasts are also seen as representing the three forms of martyrdom. St. Stephen, the Protomartyr, was a martyr in desire and in act, St. John was a martyr in desire but not in act (he was miraculously saved when cast into boiling oil, which miracle resulted in his exile to the Island of Patmos),1 and the Holy Innocents were martyrs in act but not in desire. The liturgical colors traditionally assigned to each day reinforced this distinction – St. Stephen’s feast with red, St. John’s with white, and the Holy Innocents’ with violet.2 The importance of these feasts was also manifested in that each, in addition to Christmas, was celebrated with an octave. But there is another discernible theme running through these feasts and that is the Hebrew tribe of Benjamin.

Depending on where the stoning of St. Stephen, the first martyr after the Resurrection, occurred, he may have been martyred in the territory of the tribe of Benjamin as the city of Jerusalem is divided between the territories of the tribes the Judah and Benjamin (Act 7:58). More clearly, the conversion of the Apostle Paul, of the tribe of Benjamin (Phil 3:5), is attributed, at least in part, to the prayers offered up by Stephen for those persecuting him (Act 7:59). For Paul was present and held the cloaks of those conducting the execution, thus consenting to it.

St. John can also be seen as having a connection to the tribe of Benjamin. But in order to understand this, it is important to recognize, as Dr. Brant Pitre explains in his Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary – Unveiling the Mother of the Messiah, that the person of Joseph, son of Jacob/Israel and Rachel, is a type or foreshadowing of Our Lord and Rachel of Our Lady. As Dr. Pitre spends an entire chapter explaining these connections, a full analysis cannot be presented here, but it is important to note that Joseph and Benjamin were brothers, the sons of Jacob/Israel and Rachel and that Rachel was the most-favored and most-beloved wife of Jacob. This is why Joseph was favored by Jacob above the rest of his brothers. He was the firstborn of Rachel, the most-beloved wife. Joseph, for his part, showed special love and affection for his only full-brother, Benjamin, the younger son of Rachel.

The Benjaminite connection with St. John the Apostle comes from his crucifixion account where Our Lord, the new Joseph, gives St. John to Our Lady, the new Rachel, as a second son. The second son of Rachel, as was stated, was Benjamin. Following the pattern, this would make St. John a new Benjamin. Dr. Pitre argues the St. John was aware of this as he never names himself in his Gospel, rather he calls himself the “disciple whom Jesus loved.” For in the Book of Deuteronomy (33:12), it is written that Benjamin is “beloved of the Lord.” Dr. Pitre’s position can be summarized as follows:

In order words, just as Benjamin was specially loved by Joseph because they were both sons of Rachel, so John is especially “loved” by Jesus because they have the same mother. Just as Joseph was the firstborn son of Rachel in the Old Testament, so Jesus is the firstborn son of Mary in the New Testament. And just as Benjamin was the “son” of Rachel’s “sorrow” [Rachel originally named her second son “Benoni, that is, the son of my sorrow: but his father called him Benjamin, that is, the son of my right hand” (Gen 35:18)], because she had to die to give birth to him, so John becomes the “son” of Mary’s sorrow, because Mary becomes his mother only through the anguish and “sorrow” that she experiences at the foot of the cross.3

Finally, there are the Holy Innocents. The connection between the Holy Innocents and Benjamin is made explicitly by Scripture itself, for in their regard St. Matthew in his Gospel draws from this prophecy of Jeremias: “then was fulfilled that which was spoken by Jeremias the prophet, saying: A voice in Rama was heard, lamentation and great mourning; Rachel bewailing her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not” (Mat 2:17-18). This prophecy is applicable because Rachel “was buried in the highway that leadeth to Ephrata, this is Bethlehem” (35:19) and it was not just the babies in Bethlehem who were martyred, but also those “in all the borders thereof” (Mat 2:16), and Bethlehem, although in the territory of the tribe of Judah, is close by the territory of the tribe of Benjamin, whose mother was Rachel. As such, the horror ordered by Herod would have spilled over from the territory of the tribe of Judah into that of Benjamin also. The Roman Church recognizes the connection of the Holy Innocents with tribe of Benjamin by appointing the Church of St. Paul Outside the Walls as the Station Church for this feast. As stated above, St. Paul was of the tribe of Benjamin.

The question can now be asked, what is the purpose of the theme of Benjamin present in these feasts? In the first place, Benjamin, by association, brings to mind Joseph and Rachel. As such, these feasts shed light on the two major feasts between which the Comites fall. On Christmas Day, the beloved Son of the Father was born from the most-beloved Spouse of the Holy Ghost, the Blessed Virgin Mary, the new Rachel. This Son will be condemned by those to whom He desires to be close, as Joseph was, but, in the end, God, as He did with Joseph, will use the inflicted evil to save those who share in the guilt of the condemnation. Turning to the Octave Day of Christmas, it must be noted that the prophecy of Jeremias quoted in connection with the Holy Innocents was made centuries after Rachel’s death and gives witness to the belief that Rachel, although dead, was still aware of what was occurring in the land of the living and would intercede on behalf of the living. In fact, it was held that her intercession was greater than that of Moses and Abraham.4 As the new Rachel, it would be expected that Mary would also act as a maternal intercessor in heaven for those still on the earth. And this is what is found in the Collect and Postcommunion in the Mass for the Octave Day of Christmas. In these prayers, the Church invokes Mary’s intercession.

Secondly, it must be remembered that Benjamin means “son of my right hand.” In Sacred Scripture, the “right hand” is often a sign of strength or power (e.g., Ps 117:16). So, Benjamin could be understood to mean “son of my power.” Martyrdom, for its part, requires a special grace from God to undergo not only death in witnesses of the Faith, but also to endure without apostatizing the horrible tortures and pains which, in many cases, accompany the deathblow.5 In honoring the martyrs, then, Christians not only celebrated the witness provided by individual martyrs but also the victory won by Christ through them. As a special grace, a special strength, from God is needed to undergo martyrdom for the faith, each martyr can be seen as a “son of God’s power,” every martyr can be seen as a Benjamin of God. This may explain why the theme of Benjamin is present in these three feasts which represent the three types of martyrdoms.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Prior to the liturgical reforms of 1960, the Feast of St. John before the Latin Gate, which commemorated this attempted martyrdom, was observed on the universal Roman liturgical calendar as a major double on May 6th. While the feast is no longer observed, the Mass of this feast may be said on this day.

- For more information about these feasts see Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, 2 (Christmas). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000).

- Pitre, Brant. Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary – Unveiling the Mother of the Messiah. (New York: Image Press, 2018), 177.

- Pitre, 168.

- For example, see Garrigou-Lagrange, Réginald. The Priest in Union with Christ. Part 3, Section 2, Chapter 3

December 26, 2022

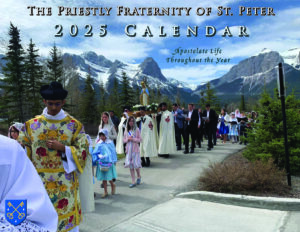

FSSP Advent 2022 Photopost

As we wind down Advent this week and prepare ourselves for the joyous celebration of Christ’s birth, we share some Advent photos from various Fraternity apostolates in North America.

December 21, 2022

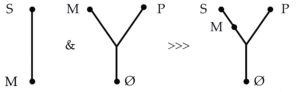

Visual Logic: A New Book by Fr. John Rickert

Fr. John P. Rickert, FSSP published a new book in August called Visual Logic: Seeing Classical and Modern Logic, An Introduction. He graciously agreed to answer a few questions on the book and address topics that may be of interest to our readers. –ed.

Q: Why is logic an important subject for Catholics, even those of us who don’t have a career in philosophy or mathematics?

A: Logic, at least to some extent, is necessary for meaningful communication. We have to understand correctly what is being asserted and what is not being asserted, and we have to see whether truths are connected, and if so, how.

Q: In the book you decry the separation of classical and modern logic. Our FSSP readers probably need no convincing of the former’s value! So what, in your view, have modern theorists brought to the table that has advanced the subject?

Q: In the book you decry the separation of classical and modern logic. Our FSSP readers probably need no convincing of the former’s value! So what, in your view, have modern theorists brought to the table that has advanced the subject?

A: The most important contribution of Modern Logic, in my opinion, was the discovery that logic itself has limits; logic proves that there are true statements that cannot be proved. As the saying goes, “Truth is greater than proof.” In my view, this truth is so important that every educated adult should be aware of it. Modern Logic has also developed in various directions, such as Modal Logic, that the ancients had only glimpses of.

Q: You mention how Kurt Gödel showed the limitations of arithmetic in the 1930s, in contrast with David Hilbert who didn’t seem to admit any such limitation. Is there a wider lesson here about human knowledge that you are pointing to?

A: Yes. The fact that science relies so heavily on mathematics will mean that, at least in theory, there are questions that science will never be able to answer. “Theories of Everything” are an exaggeration, considering that only about 4% of matter is understood and 96% remains a mystery. But even aside from these percentages, there is the more fundamental point that science doesn’t have all the answers. Indeed, science doesn’t even have all the questions.

Q: Logic seems like a very abstract thing to study. But you point out that real-world electronics and computers depend on it. How?

A: Computers, cell phones, and practically anything programmable such as microwaves use “logic gates” that implement logical ideas such as “and,” “or,” “not,” and “if.” The logical framework they use is due to George Boole and is also a great triumph of Modern Logic. In a way it is remarkable that people can use these inventions without having to know the underlying logic, but it is intellectually rewarding to have some idea of what is going on deep down.

A: Computers, cell phones, and practically anything programmable such as microwaves use “logic gates” that implement logical ideas such as “and,” “or,” “not,” and “if.” The logical framework they use is due to George Boole and is also a great triumph of Modern Logic. In a way it is remarkable that people can use these inventions without having to know the underlying logic, but it is intellectually rewarding to have some idea of what is going on deep down.

Q: You spend several pages on the meaning of the word “if”, and it ends up in a pretty weird place!

A: It does! I think this is an example of why I say that logic straddles both mathematics and philosophy; it does not fit exclusively into either one of these. Ultimately, for logicians, “if” becomes a technical term, like the terms “and,” “or,” and “not,” and then one proceeds on the basis of the definition. Still, this convention does leave a significant gap between what a mathematician or logician means by the word and what all of us in everyday life mean by it, and there are some weird results.

Q: How do visual representations, like the I-graph system or Venn diagrams, help us understand logic?

A: It is a commonplace among mathematicians that most people are either more “computational” (algebraic) or “geometric” (visual) in how they like to understand things. Of course, some are highly gifted at both ways of understanding something. Modern Logic is very heavily algebraic in its approach. There are good reasons for this: For one thing, one can check a proof as mechanically as one can check a calculation. Still, the intuitive side of logic can easily be lost in this approach.

A long time ago, when I studied logic for the first time, I read a very classical treatment that used the system of moods and figures. I am not sure whether I really “got” it, to be honest, but the thought lingered with me for a long time that there must be a clean, simple, easy way to see logic so that it is obvious, and not just the application of memorized rules.

All of sudden, in 2018, it hit me how to represent statements visually, and that combining the diagrams would visualize a syllogism. I have not seen this treatment elsewhere, so a major reason why I wrote the book was to present this approach. I must give my guardian angel a lot of credit. In fact, some very helpful insights came to me even in the course of writing the book.

Q: Who do you think would benefit most from this book?

A: My hope is, if this is not too ambitious, those who are perhaps curious about logic but find it too off-putting, or those who have felt somewhat frustrated by what they have seen of it before. I would be delighted if others experience the sort of “Eureka!” that I did.

Visual Logic: Seeing Classical and Modern Logic is available at Amazon.com.

December 2, 2022

A Priest Forever: Giving Tuesday 2022

It’s Giving Tuesday, and the FSSP priests need your help. We’ve launched the Priest Forever Fund to provide for the physical needs of FSSP priests even when they aren’t able to be active in parish life. But it won’t succeed without you.

Our goal is to raise $200,000 today. Thanks to our generous friends who have given in advance, we’ve already raised $36,507. That leaves us with $163,493 to raise in the next 24 hours.

With your help, we’ll be able to take care of our priests for life!![]()

November 29, 2022

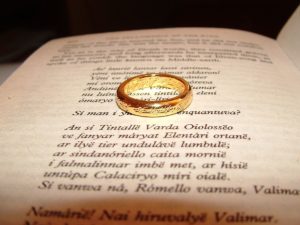

Tolkien’s Creation of Species

As Amazon has released and wrapped up their first season of “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power”, regardless of how the show has performed, it is safe to say that the imaginative world of J.R.R. Tolkien is back on the menu. For many, it is an opportunity to delve back in to a world of fantasy that formed many of our imaginations in our youth; for others, perhaps it is a first taste and an invitation to truly explore this world in its source material for the first time. While the world created by Tolkien is a fantasy, it is a fantasy that comes from the mind and imagination of a Catholic man, and in this way there are many aspects that are imbued with a elements of Catholic faith and symbolism. To this end we offer the following reflection on some of the Catholic symbolism and imagery contained in the world of Tolkien, originally presented by our French district in their publication “Claves”.

Originally published at Claves.org. Translated by Anastasiia Cherygova.

Who are the creatures inhabiting the world of “The Rings of Power”?

The series produced by Amazon opens with a very quick indication of the creation of the world of rings, elves, dwarves and many others – in Tolkien’s writings, these species tell us much about ourselves by means of a symbolic device of a fairy tale, which is possible to decode through the author’s own correspondence.

Introduction: Biblical Allegory or Christian Fairy Tale?

The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings are fairy-tale-like works whose inspiration is inherently Christian. Tolkien formally stated that: “The Lord of the Rings is, of course, a fundamentally religious and Catholic work”.1 However, one must understand in what way it is such: Tolkien never intended to create an allegory of revealed mysteries, like, for instance, was done in the Chronicles of Narnia of his friend C.S. Lewis.2

The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings are fairy-tale-like works whose inspiration is inherently Christian. Tolkien formally stated that: “The Lord of the Rings is, of course, a fundamentally religious and Catholic work”.1 However, one must understand in what way it is such: Tolkien never intended to create an allegory of revealed mysteries, like, for instance, was done in the Chronicles of Narnia of his friend C.S. Lewis.2

According to Tolkien, in allegories, the author would use a sort of “code language” which one would then decipher.3 Once the audience discovers how, all the symbols become transparent; for instance, that of Aslan being Christ, the White Witch being the devil, etc.

Tolkien did not write that way: he does not seek to impose on his audience a single framework for decoding. He is also not the master of his work to the point of telling what aspect of the “secondary world” corresponds verbatim, word for word, to another aspect of the “primary world”. Instead, he presents which figures of his fairy tale can be compared to a certain reality because the aforementioned figures are more or less consciously inspired from these realities.4 Thereby we get what we could call a diffused Christian symbolism, spread throughout Tolkien’s entire written corpus, so that every reader may, if desired, put oneself to the task and recognize it. On the surface, The Lord of the Rings does not advertise itself as a Christian work. Yet in its essence and central inspiration it is such a work. From time to time, perhaps even often, in one or another character or situation, a Christian idea would present itself, becoming almost evident, but the reader must be willing to see it.

1. A Christian-Inspired Mythology: Eru, Valar and Maia

Tolkien’s fantasy work begins in The Silmarillion with what could be called a creation myth of his world. Yet from the first lines it is obvious that this creation myth is born of a Christian inspiration. First and foremost because there is only one god. Tolkien’s secondary world is not explicitly Christian – there is no question about the Trinity – but it is basically monotheistic. Everything that exists proceeds from the only god named Eru (the Only One) or Illuvatar (the Illuminator). The first creation, in turn, consists of pure spirits called Ainur (meaning Blessed or Saints) or Valar (meaning Powers or Authorities). Whom do Ainur/Valar resemble in the primary world? With whom are they “associated”? Tolkien responds to this in numerous letters: with angels.5 These are created spirits among whom exists a hierarchy. Some rest with the Only One to sing the eternal music of creation. They are like the seraphim (“angels in waiting”) in the terminology of Dionysius Areopagite. Others are closer to the visible world, Earth, Arda in The Silmarillion, which would become “Middle Earth” after a great cataclysm, reminding us of the Biblical flood and especially the Atlantis myth. These are like the archangels (“sent angels”), working on a mission in the visible world for the sake of its inhabitants. Valar are themselves Ainur, the angelic spirits of the first order that the Only One sent on Earth, and these Valar in turn sent the spirits of a lesser order, Maia. Gandalf is one of the Maia, the most loyal and the most active, sent by Valar in the third age of the world to help humans in their battle against Sauron, who is himself a fallen Maia.

Thus, there is an entire invisible host of creation in Tolkien’s secondary world, a hierarchy of spirits created by the Only One that clearly harkens back to the angelic orders of the Christian revelation. Gandalf was compared by Tolkien to a guardian angel, akin to the guardian angel of Middle Earth.6 And through a character like Gandalf, Tolkien reminds us that the lot of humans in visible creation does not depend only on the visible causes. Instead, humans depend, first and foremost, on the actions of invisible, but completely, real forces. Forces that could sometimes become visible, and that are always helping us or harming us. Man thus belongs to two worlds: to the invisible world through his soul and to the visible world through his body. His battle is therefore primarily a spiritual one, bearing a challenge that surpasses the visible world.

2. Man and His Images: Elves, Dwarves and Hobbits

One of Tolkien’s ideas consists in the fact that, before the “fourth age”, the age of human dominion, many species would appear on Earth and prepare it for the reign of man. These are Elves, the firstborns of the Only One in Arda, as well as Dwarves and Hobbits, or halflings. Why go with these imaginary species, at times similar to man, yet also different from him? Tolkien himself answers quite clearly: elves, dwarves and hobbits are in and of themselves images of man and his nature, with his very complex and very different capacities and aspirations.

Elves

Elves, as writes Tolkien, “represent the artistic, aesthetic and purely scientific aspects of human nature elevated to a higher degree than what we find among humans”. This is why elves are passionate about art, poetry, music, but also sciences. They very much like to work with matter to improve and beautify it. In addition to this, elves possess certain privileges that allow them to attain in their work great perfection. Privileges that are inaccessible for fallen man, specifically immortality. Tolkien specifies that this immortality is limited, measured by the life of the physical world itself. Elves last as long as the Earth itself lasts, until the end appointed by Eru. What will come of them afterwards is not indicated.

Does this suggest that elves are akin to humans raised to perfection in every way, freed from all human foibles? The answer is no: elves could be killed. Even more significantly, they are morally fallible, like all creatures. They could become prideful, egotistical, excessively possessive, as represented in the storyline of The Silmarillion. Elves could become entangled in attachment to their craft to the point of rejecting one of the most essential characteristics of the world: its finitude, its corruptibility, its proneness to change and, ultimately, to destruction. This is the tragedy of the elves: they are immortal, but the created world, which they love deeply, isn’t. If they revolt against this condition, they subsequently become the “embalmers”, those who in vain attempt to rid the present world from its eventual change and from its finitude, constraining it in a “perfect” state, at least in the elves’ eyes.7 They thereby fall victim to the temptation of a kind of transhumanism.

Thus, elves constitute for us, just as Tolkien’s other imaginary species, at one and the same time an example and a warning. If you could surpass yourself by science or by art, if you could create a truly beautiful masterpiece, or if you could discover through your research new scientific realities, you will overcome death as long as it is allotted to you, being “sagely elf-like”. But if you would flee into the aesthetic dreams, if you would become egoistical and possessive about your knowledge or your art, if you would enclose yourself in the nostalgia for a bygone past, then you would become “foolishly elf-like”, degrading yourself by what is supposed to elevate you.

Dwarves

When it comes to the dwarves, they represent an “earthly” side of human nature; the desire to work the land, to extract its various riches, to construct sturdy homes that would defy time. That’s why dwarves are small – close to the ground – robust, capable stone masons, blacksmiths and exceptional goldsmiths, living in mountains and caves. They are brave and tough, but they could also be terribly stubborn, spiteful and prone to unbridled greed, the traits that are exemplified by dragons. This was the situation of Thorin in The Hobbit. The dwarves of Tolkien tell us: “Work the land, shape gold and silver, but do not become voracious like the dragons because you are made for something greater than this.”

Hobbits

Finally, hobbits are an ordinary humble people of simple tastes, with a penchant for good food and cozy homes. They are “average men”, whence comes their small size. They are often too limited, too down-to-earth homebodies, but they are also capable of rising to heroism, if they are helped by their greaters. It is the meeting with Gandalf and the elves that would reveal the dormant heroism of Bilbo and subsequently that of Frodo and Sam.

Conclusion

Through his imaginary species, Tolkien managed to present a lively and convincing image of the possibilities of human nature, of all its strengths and its desires, which could ennoble man or at the same time degrade him. The perfect man would be the one who is able to embody simultaneously the contemplative spirit of the elves, the readiness to work and the patience of dwarves, and the good sense of realism of hobbits. In creating a fellowship of two humans, four hobbits, an elf and a dwarf together around Gandalf, “the guardian angel” of Middle Earth, in their battle against Sauron, it is as if Tolkien tells us: do not neglect anything that you have within yourself, cultivate your best gifts and let the grace of God purify them and elevate them. This is how you will contribute, for your part, to pushing back against evil and increasing the good in the world.

References

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Letters, Letter No. 142 to Fr. Robert Murray, (S.J.), p. 332.

- Tolkien would reiterate this affirmation more than once in his correspondence. For example, in letter 181 to Michael Straight, dated approximately January or February 1956 (estimated), op.cit., pp. 447-448: “There is absolutely no (underlined within text) moral, political or contemporary “allegory” in this work. It is a “fairy tale”, but written – according to the conviction that I previously expressed in a long essay “About the Fairy Tale”, that it is an appropriate audience – for adults. For I think that fairy tale has its own way of reflecting about the “truth”, different from the one expressed in allegory, in satire or in “realism” – and in a certain way a more powerful one.”

- Tolkien underscores several times in his letters that he himself discovered certain characters and certain events of his story in the process of writing. He was personally quite surprised by it. Cf., for instance, letter 163 to W.H. Auden, pp. 416-417.

- We find a good example of this viewpoint in the already cited letter to R. Murray. Father Murray had written to Tolkien that the elf-queen Galadriel made him think of the Virgin Mary. Tolkien answers him by saying: “I think I see exactly what you mean (…) by your references to Our Lady, on whom is built all of my own perception, a limited one, of beauty, in majesty and in simplicity alike” (Letter 142, p. 331). Tolkien did not at all conceive Galadriel as an allegory of the Blessed Virgin. But the Blessed Virgin represents for him an ideal of feminine beauty. In imagining a very beautiful elf-queen, that is to say a human woman, but endowed with a fairy-like beauty which surpasses all the possibilities of this world, he could not have not been inspired, even unconsciously, by the idea that he got from the Blessed Virgin Mary. He thus gave to Galadriel the traits that are “associated” to the Blessed Virgin.

- For example, letter 153 to Peter Hastings, op. cit., p. 373: “The immediate authorities are the Valar (the Powers or the Authorities): the “gods”). But they are only created spirits – of an elevated angelic order, we should say, assisted by lesser angels – worthy of reverence, thus, but not of adoration.”

- Cf. Letter 156 to Robert Murray, November 4, 1954, p. 389: “I would venture to say that he (Gandalf) was an ‘angel’ incarnate, strictly speaking about an ἀγγελος: that is to say, with other Istari, mages, ‘those who know’ (Istari is translated as “wizard” because of a link with the words “wise” or “witting”, mind and knowledge, specified by Tolkien, p. 399), an emissary of the Gods of the West, send to the Middle Earth while a formidable crisis provoked by Sauron was looming on the horizon.” Tolkien well specifies in this letter in what sense Gandalf is really “dead” following the battle with the Balrog, and the fact that his return, with a new body, endowed with greater powers, is not thanks to the Valar, but to the Creator.

- Cf. Letter 181, p. 455 : “Like if a man should hate a very long, unending book, fixating himself on the chapter that he likes the most.” Some elves have “fallen into the trap of Sauron” that the art rings taught them because they had an excessive desire for power, in hopes of “stopping the change, keeping everything new and beautiful, forever.”

November 23, 2022

Advent – Preparation not Anticipation

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

As early as the day after Halloween, Christmas music begins to be heard. Perhaps even earlier, stores will decorate for Christmas with the associated holiday wares displayed. Throughout December, TV channels will play collections of Christmas movies. Then, on the 26th of December, it all comes to screeching halt. Trees are out on the curb, decorations come down, and we return to our regularly scheduled programing. This way of keeping Christmas, and the days leading up to it, is not the way our Catholic forefathers would have kept it. Christmas and its days were celebrated as Christmas, while the days leading up to Christmas, the days of Advent, were kept as days of preparation, not anticipation.1

As Lent is a penitential period of preparation for Feast of the Resurrection of Our Lord, so Advent (from the Latin for “a coming, an approach, arrival”)2 was a penitential period of preparation for the Feast of the Nativity of Our Lord and for receiving the special graces which accompany it. Advent, then, was considered a mini-Lent. While Church Law has not bound the Latin faithful to penance during Advent in some time, the season still carries the marks of being penitential. The Gloria is not sung during Masses of the Season, the penitential violet is worn, the Altar is not decorated with flowers, and the organ is silent. Historically, the Ite, Missa est was replaced by the Benedicamus Domino and the Deacon and Subdeacon would lay aside their vestments of joy for the folded chasuble. It is incongruous, then, for the faithful to begin keeping Christmas at home while the Church is in such a period of preparation. How then, can the faithful keep this season of Advent in a fitting way, not corrupting this time of preparation by following the world but rather in a Catholic spirit?

The first way would be to undertake acts of penance. Even if this is not currently enjoined by Church Law, it would be completely in keeping with the liturgical expression of the season. In 1962, the Vigil of Christmas (which is Christmas Eve day, not anticipated Masses said in the evening of the 24th and not the Midnight Mass, which is the First Mass of Christmas) was still kept as a day of fasting and complete abstinence. Additionally, in 1962, Ember Wednesday and Ember Saturday of Advent were days of fasting and partial abstinence (meat only at the main meal) while the Ember Friday was a day of fasting and complete abstinence. It is important to keep in mind that Advent does not only prepare for the liturgical commemoration of the coming of Christ into this world, but also for the coming of Christ into the souls of the believers, and, more, His coming at the end of time as Judge. All three provide ample reason for each to prepare his soul by penitential exercises.

When it comes to decorating, the house should not be adorned for Christmas until slightly before the feast itself. However, Advent Wreaths, Advent Calendars, and Jesse Trees can and should be used as decorations in the weeks leading up to the Nativity. The tree, as it might need to be purchased some time prior to the feast, can be set up and perhaps decorated in a way that befits this season of preparation, perhaps with violet and rose. The lights could be put on, but not yet turned on. With respect to the Nativity creche, the following schedule could be followed, coordinating with the Church’s liturgy:

-

- First Sunday of Advent – Set up the creche (stable-cave) with animals

- Ember Wednesday – Add the figure of Mary as this is the first time she is presented in a Gospel of the Season

- Christmas Eve Day/Vigil of Christmas – Add the figure of Joseph as the Gospel of the Vigil Mass is about his dream-vision

- Following the Christmas Midnight Mass – Add the figures of the Angel and of the Christ Child, as His temporal birth is recounted in the Gospel

- Following the Dawn Mass of Christmas (the Shepherds’ Mass) – Add the figures of the shepherds as the Gospel of the Mass recounts their going to the stable

- Epiphany – Add the figures of the Magi

When it comes to music, Christmas carols are best omitted until the feast itself. Advent songs are, of course, highly recommended. The Fraternity of St. Peter, the Benedictines of Gower, and the Monks of Clear Creek all have Advent albums. Songs concerning winter can also be sung keeping in mind that Winter starts astronomically at the winter solstice and the Advent Ember Days liturgically mark the transition from Autumn to Winter. Note too that historically at the liturgy of the First Sunday of Advent, clerics would transition from the Autumn to the Winter volume of the Breviary. Wintery decorations would not be out of place either.

Several feasts punctuate the Season of Advent, such as the Feasts of St. Barbara (December 4th), St. Nicholas (the 6th), St. Lucy (the 13th). Each have their particular home-traditions which the faithful would do well to observe.

Special attention should be given to the Magnificat antiphons sung at Vespers from 17th to 23rd of December inclusively, the Greater Ferias of Advent. These antiphons are known as the “Great Antiphons” or the “O Antiphons” (as they all start with “O”). Unlike throughout the year, these Magnificat antiphons are sung standing. Each antiphon invokes the Messias under a different title: Sapientia (Wisdom), Adonaï (Lord), Radix Jesse (Root of Jesse), Clavis David (Key of David), Oriens (Orient / Day-spring), Rex Gentium (King of the Nations / King of the Gentiles), and lastly Emmanuel (Emmanuel / God is with us). The first letter of each of these titles can be read as a backwards acrostic which spells, in Latin, “Ero cras,” meaning “Tomorrow I will be [there].” These Antiphons are the basis of the hymn “O Come, O Come Emmanuel.”

Having kept Advent in such manner, the faithful will be much better prepared to celebrate Christmas and receive the special graces of the season than had the practices of the world been followed. When the time comes, Christmas should be kept as Christmas, with the decorations, carols, food, and all of the trimmings! This celebration should be extended at least until the Feast of the Epiphany (the 13th Day of Christmas), or the Commemoration of the Baptism of the Lord (the Octave Day of the Epiphany), or even to the 40th and Last Day of Christmas, Candlemas.

William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Much of the historical and liturgical information contained within this article comes from Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, 1 (Advent). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), chapters 1-3.

- Lewis and Short, s.v. “Adventus.”

November 21, 2022