Pray for Fr. James Buckley, FSSP

Please pray for Fr. James Buckley, FSSP. Father has been experiencing health problems over the past few months which have recently worsened and are compounded by his advanced age. Father has been with the Fraternity of St. Peter for thirty years.

Please pray for Fr. James Buckley, FSSP. Father has been experiencing health problems over the past few months which have recently worsened and are compounded by his advanced age. Father has been with the Fraternity of St. Peter for thirty years.

September 14, 2023

“Forget not the Groanings of thy Mother”

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

In a previous article it was related that the 40 days between the Feast of the Transfiguration and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross represent, through the lens of Our Lord’s Resurrection, a recapitulation of the 40 of Days of Lent with the Feast of the Exaltation being a recapitulated Good Friday. This all being the case, it is not unreasonable to ask if there is, following this recapitulated Good Friday on September 14th, a recapitulated Holy Saturday on the following day, September 15th.

Holy Saturday, for its part, marks the day when Our Lord’s Body rested in the tomb and His soul abided in the Limbo of the Fathers. It was also on this day that only Our Lady, of all of His disciples, kept faith in her Son. On this point, in his entry for Holy Saturday, Dom Guéranger wrote the following:

And now let us visit the holy Mother, who has passed the night in Jerusalem, going over, in saddest memory, the scenes she has witnessed. Her Jesus has been a victim to every possible insult and cruelty; He has been crucified; His precious Blood has flowed in torrents from those five Wounds; He is dead, and now lies buried in yonder tomb, as though He were but a mere man, yea the most abject of men. How many tears have fallen, during these long hours, from the eyes of the daughter of David!…Mary alone lives in expectation of His triumph. In her was verified that expression of the Holy Ghost, where, speaking of the valiant woman, He says: “Her lamp shall not be put out in the night” (Prov. xxxi. 18). Her courage fails not, because she knows that the sepulchre must yield up its Dead, and her Jesus will rise again to life. St. Paul tells us that our religion is vain, unless we have faith in the mystery of our Lord’s Resurrection: where was this faith on the day after our Lord’s death? As it was her chaste womb that had held within it Him whom heaven and earth cannot contain, so, on this day, by her firm and unwavering faith, she resumes within her single self the whole Church. How sacred is this Saturday, which, notwithstanding all its sadness, is such a day of glory to the Mother of Jesus! It is on this account that the Church has consecrated to Mary the Saturday of every week.1

Providentially, the day following the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross is a feast of Our Lady, a feast whose object is the sufferings of the Mother of God, including those she experienced during the Passion of her Son – the Feast of the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary. As with the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, this September Feast of the Seven Sorrows2 can be seen as a recapitulation, through the lens of Our Lord’s Resurrection, of what was observed during Holy Week.

But this September Feast of the Seven Sorrows serves another purpose. On the 8th of September, Holy Mother Church celebrates the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The September feast of the Seven Sorrows falls on the Octave Day of Our Lady’s Nativity. So not only can the September Feast of the Seven Sorrows be seen as a recapitulated Holy Saturday, it is also connected with the Feast of the Nativity of Our Lady.

As such, it can be argued that there is a fittingness to having this Feast on the Octave Day of Our Lady’s Nativity. The Octave Day of Our Lord’s Nativity marks Our Lord’s Circumcision, when He first shed His Blood for us and received His Name, which means “Savior” or “the Lord saves.”

In the 1957 translation of the Raccolta – a book which is a collection of the various prayers which were then indulgenced – is found the meanings the Church has recognized in these two interrelated events – Our Lord’s Circumcision and the conferral of His Name – on the Octave Day of His Nativity. She expresses herself as follows: “Jesus, sweetest Child, wounded after eight days in Thy circumcision, called by the glorious Name of Jesus, and at once by Thy Name and by Thy Blood foreshown as the Savior of the world, have mercy on us.”3

Just as the events which occurred eight days after Our Lord’s birth foreshadowed, at least in part, His mission, it is fitting that there be a feast around the birth of Our Lady which expresses the same on her behalf. There cannot be a complete unity of expression between Our Lord and Our Lady on these points as Jewish baby girls do not undergo the rite of Circumcision on the 8th day after their birth. But having a feast on the Octave Day of her Nativity which touches on the newborn Queen’s future sufferings mirrors well the feast on the Octave Day of her Son’s Nativity which touches on His future sufferings. For just as Our Lord was predestined to be the Man of Sorrows, so was Our Lady predestined to be Our Lady of Sorrows. Even more, for, as the Church sings in the Communion for the feast of her sorrows, Our Lady merited the palm of Martyrdom as she stood at the foot of the Cross. She is rightly and properly titled, then, “the Queen of Martyrs.” Additionally, just as the Octave Day of Our Lord’s Nativity also commemorates Our Lord’s reception of His Name, so within the eight days of the Nativity of Our Lady, the Church keeps the feast of the Most Holy Name of Mary. This Feast of the Most Holy Name of Mary falls on the 5th Day of the Nativity of Our Lady, that is September 12th.4 So not only does this time of the Liturgical Year provide the faithful a recapitulation of Lent, it also serves as a mirror of Our Lord’s Nativity through these feasts of Our Lady.

And just as Our Lord underwent His Passion and Death for our sake, so did Our Lady undergo her Sorrows for us also, the modes being different, of course. For we read in the Book of St. John’s Apocalypse, the Book of Revelation, “And a great sign appeared in heaven: A woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars. And being with child, she cried travailing in birth: and was in pain to be delivered…And she brought forth a man child, who was to rule all nations with an iron rod. And her son was taken up to God and to his throne” (Apo 12:1-2, 5). While these verses can admit of various, non-contradictory interpretations, one interpretation understands this woman symbolizing Our Lady, and the child symbolizing Our Lord. After all, He is to “rule all nations” and was taken up to the Throne of God, being equal with God. But this leaves the issue of her “travailing in birth” and being “in pain to be delivered,” for Our Lady did not suffer any labor pains in the birth of Our Lord.5 So, the questions must be asked, for whom is she suffering these labor pains and what exactly are these pains?

To find an answer to these questions, it should be noted that what was quoted earlier as “and being with child” is more an interpretation than a literal translation. The Latin, following the Greek, is “et in utero habens,” literally, “having” or “holding in the womb.” The Greek and Latin do not specify how many children the woman is holding in her womb, just that she is expecting. Giving this text as “being with child” reflects what follows in the proximate verses, but this is perhaps too restrictive. As it will be explained shortly, the more vague, “holding in her womb,” conveys a deeper spiritual reality. Additionally, it should also be noted that what is translated as “was in pain” in the Greek (“βασανιζομενη”) comes from the word “to torture,” the Latin being “cruciatur,” literally meaning she is being crucified, tormented, tortured, in order that she may deliver. These are not normal labor pains.

A few verses later, St. John explains that the woman had other children, namely, those “who keep the commandments of God and have the testimony of Jesus Christ” (12:17). Surely, she held these other children in some way in her womb, in some way gave birth to them. And would not these “who keep the commandments of God and have the testimony of Jesus Christ” be all true Christians? Therefore, all true Christians are children of this woman, the Blessed Virgin Mary, held in her womb in a certain manner and then born by her, in pains and sufferings which are compared to being tortured, being crucified. This reinforces the interpretation which says that at the Foot of the Cross, when Our Lord said to Our Lady and to St. John, “behold thy son…behold thy mother” (19:26-27), that Our Lord was giving His Mother as Mother to all of the Faithful in the person of St. John. It was not by accident that this occurred at the Foot of the Cross, for here she suffered, was crucified, tormented, tortured, in her Sorrows so that she might give supernatural life to us, her children, as a mother suffers for her natural children.

It is written in the book of Sirach, “forget not the groanings of thy mother” (7:29) which she suffered in giving you birth. If such is true regarding our natural mothers, how much more so should this apply regarding our Mother in the spiritual life, in the life of grace?

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Guéranger, Prosper. The Liturgical Year, vol. 6 (Passiontide and Holy Week). Trans. Shepherd, Laurence. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), pp. 547-9.

- The Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary are also commemorated on the Friday of Passion Week, the Friday before Good Friday.

- The Raccolta. Trans. Christopher, Joseph P., Spence, Charles E., Rowan, John F. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2004 a reprint of Boston: Benzinger Brothers, Inc., 1957), p. 69 (126, V).

- Previously kept on the Sunday within the Octave of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

- See Ott, Ludwig. Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma. Trans. Lynch Patrick. Edited by Bastible, James. Updated by Fastiggi, Robert. (Baronius Press, 2018), p. 222.

September 8, 2023

Video History of St. Vitus Church in Los Angeles

Seminarian Rev. Jacob Sievek has put together a wonderful video history of St. Vitus Church, an FSSP parish founded in San Fernando for the preservation and proliferation of the Latin Mass to the Los Angeles faithful. Watch the video below and check out the FSSP LA Youtube channel for more about the parish. Thank you Fr. Fryar for sharing this with us!

August 18, 2023

The Confraternity of St. Peter: Revisiting an Important Work

Behind every spiritual work, every growing apostolate, every deep conversion is prayer. Without prayer, nothing truly and eternally good ever happens. God has willed that many of the blessings He wishes to bestow upon His children be won for them by means of prayer.

And for the important work of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter it is no different. The Church has always understood this and that is why the heights of Catholic Culture were always built upon the strong foundation of contemplative prayer. Without that heart-to-heart conversation with God, there would be no soul to the apostolate.

The zeal of priests and laity alike fades over time if the fire of Divine Charity is not kept close to their hearts by prayer. Thus, the priests of the FSSP rely most upon the generous prayerful support of those many souls who daily lift them up in prayer into contact once again with the Most Sacred Heart of Our Beloved Savior and Eternal High Priest.

For any who value the work of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, there is a beautiful way to band together to support the priests and seminarians of the FSSP and it was established with Papal Approval more than 15 years ago. It is known as the Confraternity of St. Peter.

The Confraternity of St. Peter is a sodality of members who wish to unite themselves to the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter and aid in the work of our Fraternity, primarily by their prayers. Already the ranks of the Confraternity of St. Peter include those from all walks of life and every level of the hierarchy of the Church. Clerical or Lay, there are many who, although they may not even have been able to meet an FSSP priest in person, nevertheless generously participate in the apostolic labors of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter by their daily prayers and sacrifices.

What a magnificent way Our Lord established His Church and the economy of salvation! Even if one thinks one has nothing to give, there is this beautiful chance to be a part of the spiritual family that seeks to sanctify priests and people by means of the Traditional Roman Liturgy, Sacraments, and Breviary in full communion with the See of St. Peter.

What is the Confraternity of Saint Peter?

It is a society which gathers those who feel close to the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter and who wish to support its charism through prayers and sacrifices.

Thus, the Confraternity contributes to the service of the Church, through supporting numerous vocations, the sanctification of priests and their pastoral endeavors.

Members commit themselves to:

Every day:

1. pray one decade of the holy rosary for the sanctification of our priests and for our priestly vocations

2. recite the Prayer of the Confraternity

Once a year:

3. have the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass offered once for these intentions.

What spiritual benefit do members receive from the Confraternity?

Their commitments place the members among our most faithful benefactors, and as such, among the particular recipients of our priests’ and seminarians’ daily prayers.

The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is offered each month for the members of the Confraternity in each area. A project is under way to show members more of the fruits of their prayers.

How does one become a member?

1. Fill out an enrollment form at https://fssp.com/enroll-in-the-confraternity/

2. The Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter will send to you in return the certificate of membership. The commitments take effect with the reception of the certificate.

3. Members must be Catholics who are at least 14 years of age.

4. Membership is purely spiritual and does not confer any rights or duties other than the spiritual support in prayer and charity in accord with the commitments described above.

5. By themselves the commitments do not bind under penalty of sin.

6. Membership and the commitments which follow it are tacitly renewed each year on the feast of the Chair of Saint Peter (February 22), unless expressly determined otherwise.

Daily Confraternity Prayer

Following a decade of the Rosary:

V. Remember, O Lord, Thy congregation.

R. Which Thou hast possessed from the beginning.

Let us pray.

O Lord Jesus, born to give testimony to the Truth, Thou who lovest unto the end those whom Thou hast chosen, kindly hear our prayers for our pastors.

Thou who knowest all things, knowest that they love Thee and can do all things in Thee who strengthenest them.

Sanctify them in Truth. Pour into them, we beseech Thee, the Spirit whom Thou didst give to Thy apostles, who would make them, in all things, like unto Thee.

Receive the homage of love which they offer up to Thee, who hast graciously received the threefold confession of Peter.

And so that a pure oblation may everywhere be offered without ceasing unto the Most Holy Trinity, graciously enrich their number and keep them in Thy love, who art one with the Father and the Holy Ghost, to whom be glory and honor forever.

Amen.

Nihil obstat: Vic. Gen. FSSP, 05.II.2007

Imprimatur: Vic. Gen. Diœc. Laus. Gen. Frib., 28.II.2007

August 14, 2023

A Recapitulated Lent

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

On the 6th day of August, Holy Mother Church celebrates the Feast of the Transfiguration which is the second time in the liturgical year when this event of Our Lord’s life is made present to the faithful through the sacred signs of the Church’s liturgy and the infused virtue of Faith.

The first was the shared Gospel of the Ember Saturday and the Second Sunday of Lent. Historically, the Transfiguration occurred in the last year of Our Lord’s public ministry and before His final departure from Galilee for Judea and Jerusalem where He would suffer (see Mat 19:1). Our Lord, knowing that at Jerusalem He would undergo His Passion for the benefit of our salvation, took with Him up the mount where He was transfigured the same three Apostles who would be with Him during His Agony in the Garden – Peter, James, and John. As they would soon see Christ suffering in the Garden, Our Lord would give them a glimpse of His glory – a glory which He always has but which He hid so that He could suffer and die for us. This glimpse of His glory was to provide them with a reason not to despair or fear at the time of the Passion. This presentation of the Transfiguration at the start of Lent serves the same purpose for the Faithful as they prepare to celebrate the liturgical commemoration of the Lord’s Passion and Death. In this light, the placing of this commemoration of the Transfiguration near the beginning of Lent can be seen as thematically fitting.

As they were descending the mountain, Our Lord told those with Him: “Tell the vision to no man, till the Son of Man be risen from the dead” (Mat 17:9). As the August Feast of the Transfiguration will always occur after Easter, after the Feast of the Resurrection, it is, as it were, those Apostles making public to the Church, after the Son of Man rose from the dead, what they had witnessed before the Passion when Christ took them “up into a high mountain apart”(Mat 17:1).1 Unlike the commemoration of the Transfiguration at the beginning of Lent, where only the Gospel (and its commentaries in Matins) is concerned with the event, in the August Feast of the Transfiguration, everything in the liturgy manifests it. This difference between these two observances serves to indicate how one presents the not-yet-made-public event and the other the event as publicly proclaimed. There is a fittingness, then, to having these two commemorations of the Transfiguration in the course of the liturgical year.

In a previous article, it was remarked that the Church, at the conclusion of the Octave of Pentecost, seemed not quite ready to leave behind her the mysteries she had been celebrating and meditating upon during Holy Week. There were, it was observed, liturgical recapitulations where pre-Easter mysteries were revisited in light of the Lord’s Resurrection. Following the Pentecost Octave and Trinity Sunday, the Thursday of Corpus Christi recapitulated Holy Thursday and, an octave later, the Feast of the Sacred Heart recapitulated Good Friday. Something similar occurs with the August Feast of the Transfiguration.

There is a tradition which holds that the Transfiguration occurred 40 days before the Crucifixion.2 This being the case, the commemoration at the beginning of Lent is not just thematically fitting but also places this commemoration at nearly the proper historical distance from Good Friday.3 Lent, however, was considered an unfitting time for a festal celebration of the Transfiguration.4 And so, the Feast of the Transfiguration was fixed by counting back 40 days from the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, an older feast which is itself a recapitulated Good Friday, one even older than that of the Sacred Heart. The Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross was originally instituted to commemorate the Finding of the True Cross and the Dedication of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.5 If the Feast of the Exaltation is a recapitulated Good Friday, and the August Feast of the Transfiguration is seen as a recapitulation of the commemoration of the same at the beginning of Lent, then these 40 days between them serve as a recapitulated Lent.

The first encounter with the Transfiguration was near the start of the 40 days of Lent. Lent itself ended soon after the adoration of the Cross on Good Friday. Forty days after the August Feast of the Transfiguration, the Cross again becomes the focus of the Church’s attention. On Good Friday, the Cross was regarded as that on which Our Savior hung in agony and died for our sins – “Behold the wood of the Cross on which hung the Savior of the world.” In September, unmixed with sorrow and horror, the Cross is exalted, held high as the banner of our salvation.

What has just been presented sheds light onto this time of the Church’s Liturgical Year. Looking at the Church’s calendar during this Time after Pentecost, it can seem that there is no order or structure to it. There are feasts and other liturgical days which, at first glance, seem simply to fill up the remaining time before Advent. But, by understanding the origins of the feasts, their connections with the celebration of the pre-Easter mysteries, and their connections with each other, a structure arises.

Such reflections will also reveal the Mind of the Church to her children, the Faithful, so that they can imitate her. Even now, in August and September, the Church keeps before her, and before her Faithful, the great price of redemption, the sufferings of Our Lord, with recapitulations of the Transfiguration, the 40 days of Lent, and Good Friday though viewed now in the light of the Resurrection. There can be the danger that the further the Faithful move away from Lent and Holy Week, what so impressed their minds then will begin to slip and grow dull. And, as these impressions and considerations grow dull, so too will the hearts which were aflame at Easter cool or even grow cold. By these post-Easter recapitulations, Holy Mother Church invites her children to renew in their minds the impressions made during Lent and Holy Week and enflame again their hearts.

May we all, then, follow this lead of Our Mother and prove ourselves true children of the Church, children after her own mind and heart.

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- See Guéranger, Prosper.The Liturgical Year, vol. 13 (Time after Pentecost Book 4). Trans. The Benedictines of Stanbrook Abbey. (Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications, 2000), p. 271-272.

- “Originally, the feast of the Transfiguration was observed in February [in the Byzantine tradition]. However, since this joyful feast fell during the time of the Great Fast [i.e., Lent], its celebration was not in keeping with the spirit of fasting and penance. Therefore, it was transferred to the 6th of August. Why this day? The historian Eusebius and St. John Damascene are of the opinion that the Lord’s Transfiguration took place forty days before the death of Christ. Thus holy Church, in keeping with this opinion, transferred this feast from the month of February to the 6th of August, because forty days later, September 14th, is the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross – the commemoration of the passion and death of Christ.” – Katrij, Julian. A Byzantine Rite Liturgical Year. Trans. Wysochansky, Demetrius. (Detroit: Basilian Fathers Publication, 1983), p. 421. But there are other traditions regarding the historical date of the Transfiguration. Dom Guéranger (1) wrote, “more than one doctor of sacred rites [Sicard. Cremon. Mitrale, ix. 38; Beleth. Rationale, cxliv.; Durand. vii., xxii., etc.] affirms that” the Transfiguration occurred historically on August 6th. The Orthodox priest Thomas Hopko presents, in his The Orthodox Faith, Volume II-Worship, the Church Year, Transfiguration, that the Transfiguration historically “took place at the time of the Festival of Booths” (September-October). If one accept this position, one would have to take into account that Jesus was in Jerusalem for the Feast of Booths which occurred prior to the Passion (see John 7:1, 9-10) and this would have to be the one, in this dating, associated with the Transfiguration as the synoptic Gospels, which recount the Transfiguration, only detail about the last year of Our Lord’s public ministry, although a date of early August might not be out of bounds thus harmonizing these two other positions. The liturgical tradition of the Latin and Greek Churches, in first placing a commemoration of the Transfiguration in the February timeframe, either fixed or moveable, argues for the position of Eusebius and St. John Damascene (the Murbach Lectionary, the second oldest lectionary of the Roman Tradition [~ A.D. 800], attest to the pericope of the Transfiguration being read on Ember Saturday of Lent). However, a West Syriac Jacobite Lectionary (Sachau_322) attests that in this tradition the Transfiguration is named the “Feast of Tents [Booths]” while celebrating the feast on the 6th of August.

- From the Second Sunday of Lent to Good Friday there are, inclusively and counting Sundays, 34 days. From Ember Saturday of Lent to Good Friday there are, inclusively and counting Sundays, 35 days. 40 days prior to Good Friday, according to the same counting method, would be the Monday of the First Week of Lent. Why, then, is the Lenten commemoration of the Transfiguration not kept on the Monday of the First Week of Lent but rather on the Ember Saturday and Second Sunday of Lent? According to Sts. Matthew and Mark, the Transfiguration took place on a 7th day. According to St. Luke, it took place on an 8th day (see here, here, here, and here). There is an affinity, then, for celebrating the Transfiguration on a Saturday (the 7th Day) and/or on the Christian Sunday (the 8th Day).

- The commemoration of the Transfiguration at the beginning of Lent is not festal. As was stated above, only the Gospel (and the Matins commentaries) are concerned with this event and the liturgy of the day reflects the season of Lent.

- In the Roman Liturgy, the commemoration of the Finding of the Holy Cross became traditionally associated with May 3rd and the September 14th date with the recovery of the Relic of the True Cross by the Roman Emperor from the Persians.

August 6, 2023

The New Founders of Rome, Part 2: The Monuments

by Claudio Salvucci

Out of the thousands of modern tourists who flock to Rome yearly, it’s doubtful that any are there primarily to pay their respects to monuments of King Romulus or the god Quirinus.

There was actually a quite famous site associated with Romulus in antiquity: the Casa Romuli or “Hut of Romulus” at the southwest corner of the Palatine, which apparently consisted of a mud-and-straw peasant’s house that had been repeatedly damaged and rebuilt over the centuries. St. Jerome lived in sight of it during his time in Rome, but he thought very little of it and was more at home with the holy places of Bethlehem.

The Romulan legacy still endures in archaeology and myth, but his story is not the one whose monuments draw the crowds.

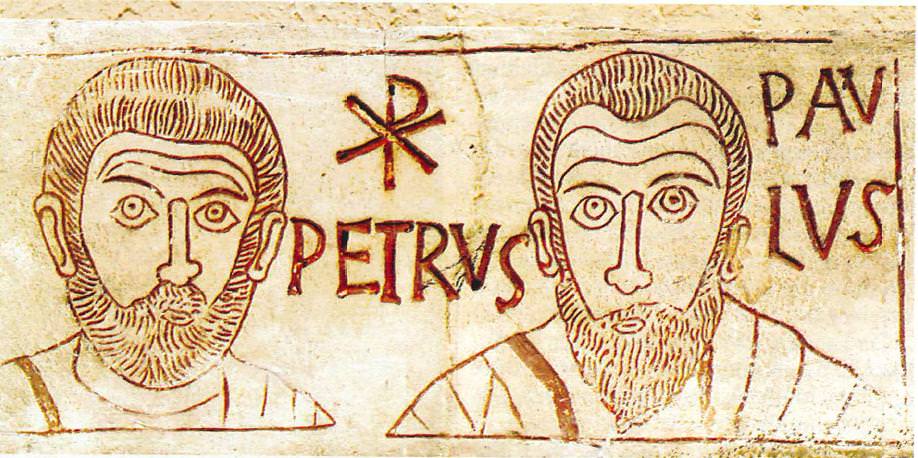

That distinction belongs to St. Peter and the Roman martyrs.

Tourism to Rome’s Christian sites can be traced back to the second century. Gaius, a local priest who flourished around the year 200, tells us the following, in a quote that was preserved by Eusebius:

“But I can show the trophies of the apostles. For if you will go to the Vatican or to the Ostian way, you will find the trophies of those who laid the foundations of this church.”

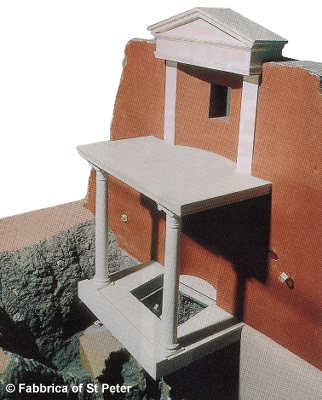

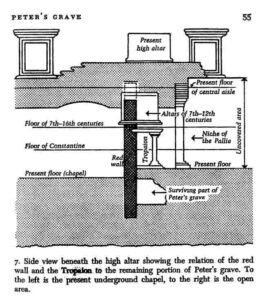

“Trophies” here is not like a modern athletic trophy but is a translation of the Greek word tropaion, a victory monument. And in fact, the monument Gaius spoke of, lost to the eyes of men for centuries, was rediscovered during the archaeological excavations under St. Peter’s Basilica in the 1940s.

The Liber Pontificalis, an ancient chronicle of the Popes, contains additional information. It states that the second and third Popes, St. Linus and St. Cletus, were both “buried near the body of blessed Peter in the Batican”. Furthermore, it states that the third Pope, Anencletus:

built and adorned the sepuchral monument of the blessed Peter, forasmuch as he had been made priest by the blessed Peter, and other places of sepulchre for the burial of bishops. There he himself was buried near the body of the blessed Peter, July 13.

We are not certain of the reliability of this information, mainly because the extant sources differ on whether Popes Cletus and Anencletus are two separate people or the same person. Moreover, the excavations have not turned up evidence for a sepulchral monument built during the years given for Anencletus: A.D. 84-95.

What archaeology has confirmed, however, is that 1st-century and 2nd-century graves surrounded Peter’s own grave, as if the deceased had wanted to be buried as close to the original grave as possible. Then, around the years 150-165, as determined by dateable bricks found at the site, Gaius’s tropaion was built at the site. As it happens, the Pope reigning from 157-168 was named Anicetus–so some scholars are convinced the Liber Pontificalis got the facts right but transcribed the name of the Pope wrong.

In any case, historical documents and archaeology both point to the fact that Peter’s grave was remembered and honored continually, starting from his earliest successors in the first century, and continuing into the middle of the second century when Christians first built a small monument over the grave.

Of course we also know that the modest monument that was first built over the tomb of the Apostle was not the last.

Of course we also know that the modest monument that was first built over the tomb of the Apostle was not the last.

But note: the sanctity of the site was such that even as subsequent Emperors and Pontiffs added to the majesty of the memorial, they shied away from destroying the work of their predecessors, instead tending to simply add to what was there already. Grave beside grave, tropaion above grave, memorial around tropaion, altar atop memorial, and finally altar atop altar.

The great Constantinian basilica that was built to honor Peter’s grave was precisely engineered over the existing tropaion–a project that required massive construction work, including leveling the natural hill and some of the necropolis that had grown up around the site. Constantine’s basilica, regrettably, is no more, but it stood for over a thousand years, and only when it was crumbling and beyond repair was an even larger and more magnificent basilica built around it.

This “new” basilica is the St. Peter’s that we know today.

And during that building process five centuries ago, the Popes created a new body called the Reverenda Fabrica Sancti Petri, the Factory of St. Peter, to manage the construction, maintenance, and decoration of the building as well as the tomb of the Apostle.

This organization is still plugging away at that task today, with no end in sight. So much so that the modern Romans have an expression “com’a fabrica de San Pietro”–“like the Factory of St. Peter”–for an interminable task that is perennially under construction and never actually finished.

As such the Basilica Sancti Petri may well serve as a metaphor for the whole church militant here on earth–still carefully guarding the Apostolic legacy it received during its earliest days, and still being built slowly and laboriously by human hands.

But still–what humanity can do with its own hands is limited. Even monuments solidly built and carefully tended still degrade and decay. Moreover, a stone monument can only remind us of ones who once walked on the earth–it is an inferior and inanimate remembrance of a living human soul.

A far better tribute would be to elevate a living person into a higher level of being. Something greater than he was. Something supernatural.

This even the pagans knew, which is why the Romans deified their first founder.

Yet they hardly expected to share his fate. Deification was a singular privilege of Romulus’s status as a demi-god and his foundation of Rome. His wife Hersilia was allowed to share his singular privilege; but that was as far as it went. As Augustine pointed out (see Part I for the quote), not even Romulus’s brother and co-founder Remus was deified.

Ordinary, mortal Romans were at best destined for the Limbo-like pleasantries of Elysium rather than experiencing any kind of transformation by the divine nature that the gods enjoyed.

Their second founder, however, taught to them a new and quite different doctrine, received directly from the lips of a Divinity:

Simon Peter, servant and apostle of Jesus Christ, to them that have obtained equal faith with us in the justice of our God and Saviour Jesus Christ. Grace to you and peace be accomplished in the knowledge of God and of Christ Jesus our Lord: As all things of his divine power which appertain to life and godliness, are given us, through the knowledge of him who hath called us by his own proper glory and virtue. By whom he hath given us most great and precious promises: that by these you may be made partakers of the divine nature: flying the corruption of that concupiscence which is in the world.

Through Christ it is not just Rome’s founder, but the Roman people themselves–all the Roman people–who are invited to partake in the divine nature. Not just Peter, but Agnes, Cecilia, Frances, and all the saints whom we honor at our altars in addition to myriads we have never even heard of.

In the eyes of eternity, and of the faithful who visit the city, these are all a part of Rome’s truest and greatest tropaion, and a more permanent memorial than a few marble columns and slabs beneath the Vatican.

July 14, 2023

I Have Given Blood to You

by Fr. William Rock, FSSP

On the first day of July is celebrated the Feast of the Precious Blood, which provides the theme for the month. It might seem, at first glance, that this Feast is paired with Corpus Christi. Corpus Christi celebrates the presence of Our Lord’s Body (Corpus Christi) hidden under the appearance of Bread. Does the Feast of the Precious Blood, then, celebrate the presence of Our Lord’s Blood under the appearance of Wine?

An examination of the texts of Corpus Christi, however, reveals that this feast, despite its name, celebrates the Eucharistic presences of both of Our Lord’s Body and His Blood. For example, the Collect, the opening prayer, of Corpus Christi reads: “O God, under a marvelous sacrament you have left us the memorial of thy Passion; grant us, we beseech thee, so to venerate the sacred mysteries of thy Body and Blood, that we may ever perceive within us the fruit of thy Redemption.”

Similarly, by examining the texts for the Feast of the Precious Blood, it becomes clear that the Feast is about celebrating, not Our Lord’s Blood under the appearance of Wine in the Holy Eucharist, but rather the Blood in Our Lord’s veins, the Blood shed in Sacrifice, the Blood hypostatically united to the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, God the Son. For even when Our Lord’s Blood was separated from His Body on the Cross, His Blood, at least a great deal of It, was still united to Our Lord’s Divinity and worthy of divine worship. The Feast of the Precious Blood can be paired, then, with the Feast of the Sacred Heart and its devotion rather than with the Feast of Corpus Christi.

But in order to understand the importance of Our Lord’s Blood and what it should mean to the faithful, one must understand the role of blood in the Old Testament.

The first mention of blood in Holy Writ is found in the Book of Genesis. After Cain slew his brother Abel, God said to Cain that “the voice of thy brother’s blood crieth to me from the earth” (Gen 4:10). Specifically, Abel’s blood was crying out for vengeance against his brother, his murderer. As a result, the earth, which received Abel’s blood, would not yield her fruit to support Cain, who was to be a fugitive upon the face of the earth.

After the Flood, when God first gave man permission to eat meat, He said:

Let the fear and dread of you be upon all the beasts of the earth, and upon all the fowls of the air, and all that move upon the earth: all the fishes of the sea are delivered into your hand. And every thing that moveth, and liveth shall be meat for you: even as the green herbs have I delivered them all to you: Saving that flesh with blood you shall not eat. For I will require the blood of your lives at the hand of every beast, and at the hand of man, at the hand of every man, and of his brother, will I require the life of man (Gen 9:2).

This prohibition against consuming blood was enacted to express that blood was, in a unique way, connected with the life of the creature, which belongs to God. This idea is expressly presented in the Book of Leviticus: “the life of the flesh is in the blood” (Lev 17:11).

The importance given to blood is also manifested in the establishment of covenants, those sacred contracts between God and His Chosen People. After the Hebrews departed from Egypt, Moses confirmed a covenant between God and the Chosen People with a ceremony involving blood – “And [Moses] took the blood and sprinkled it upon the people, and he said: This is the blood of the covenant, which the Lord hath made with you concerning all these words” (Exo 24:8). St. Paul, in his Letter to the Hebrews, relates this event as follows: “when every commandment of the law had been read by Moses to all the people, he took the blood of calves and goats, with water, and scarlet wool and hyssop, and sprinkled both the book itself and all the people” (Heb 9:19).

Blood also served as a means of protection. As the final plague which God brought upon Egypt, an angel of death was sent to slay all of the firstborn, both of man and of beast, in the land. To protect themselves, the Hebrews were instructed to take

a lamb without blemish, a male, of one year…And you shall keep it until the fourteenth day of this month; and the whole multitude of the children of Israel shall sacrifice it in the evening. And they shall take of the blood thereof, and put it upon both the side posts, and on the upper door posts of the houses, wherein they shall eat it…And I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and will kill every firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast: and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments; I am the Lord. And the blood shall be unto you for a sign in the houses where you shall be; and I shall see the blood, and shall pass over you; and the plague shall not be upon you to destroy you, when I shall strike the land of Egypt (Exo 12:5-7, 12-13).

And so it was, that the Angel of Death did indeed pass over the houses of the Hebrews thus marked with the blood of those first paschal lambs, sparing the firstborn therein.

The shedding of blood in sacrifice was given by God to the Hebrews for the expiation of sins. It is recorded in the Book of Leviticus that God spoke to the Hebrews saying: “I have given [blood] to you, that you may make atonement with it upon the altar [of sacrifice] for your souls, and the blood may be for an expiation of the soul” (Lev 17:11). The blood spilt served as a substitute for the life of the one offering the sacrifice, who deserved to die the death because of his sins. This sentiment is repeated in the Letter to the Hebrews where it is written that “without shedding of blood there is no remission [of sin]” (Heb 9:22).

The letter to the Hebrews also indicates that blood was used by the Hebrews for ceremonial purification. St. Paul relates that “almost all things, according to the law, are cleansed with blood…the tabernacle also and all the vessels of the ministry, in like manner, [Moses] sprinkled with blood” (Heb 9:22, 21)

All of these properties of blood in the Old Testament find their fulfilment in the Blood of Our Lord.

Like Abel’s blood, Our Lord’s spilt Blood cries out to heaven – “the sprinkling of blood which speaketh better than that of Abel” (Heb 12:24). But Our Lord’s Blood does not cry out for vengeance as Abel’s did, but rather it cries out for forgiveness, pardon, mercy.

Not only was Our Lord’s Blood the “the life of [His] flesh,” but it is also life-giving –

Jesus said to them: Amen, amen, I say unto you: except you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you shall not have life in you. He that eateth my flesh and drinketh my blood hath everlasting life: and I will raise him up in the last day. For my flesh is meat indeed: and my blood is drink indeed. He that eateth my flesh and drinketh my blood abideth in me: and I in him (Joh 6:53[54]-56[57]).

As with blood in the Old Testament, the Blood of Our Lord sealed the New and Everlasting Covenant with His Church – “This is the Chalice of My Blood of the New and Eternal Testament” (Roman Canon, see also Mat 26:28, Mar 14:24, Luk 22:20, 1 Cor 11:25).

Our Lord’s Blood is also a means of protection for the Faithful. St. John Chrysostom wrote in his commentary on the Gospel of John (Homily 84 in John, cap. 19), which the Church reads in her night office of Matins for this feast:

On that night in Egypt, when the destroying Angel saw the blood upon the lintel and on the two side-posts, he passed over the door, and came not in unto the house. Even so now much more will the destroyer of souls flee away when he seeth, not the lintel and the two side-posts sprinkled with the blood of a lamb, but the mouth of the faithful Christian, the living dwelling of the Holy Ghost, shining with the blood of the True Messiah. If the Angel let the type be, how shall not the enemy quail before the Reality?1

The Blood of Our Lord was shed in an atoning sacrifice – “This is the Chalice of My Blood…which shall be shed for you and for many unto the remission of sins” (Roman Canon, see also Mat 26:28, Mar 14:24, Luk 22:20).

In the First Chapter of his Apocalypse, St. John wrote: “Jesus Christ, who is the faithful witness, the first begotten of the dead and the prince of the kings of the earth, who hath loved us and washed us from our sins in his own blood” (Apo 1:5). Later on in the same book, St. John describes those who have “washed their robes and have made them white in the blood of the Lamb” (Apo 7:14). Our Lord’s Blood, then, is a means of purification from sin for the faithful.

And how is the Blood of Our Lord sprinkled on the faithful for the sake of their purification, their forgiveness of sin, their protection, their reception of supernatural life, and their incorporation into the New Covenant? How do the faithful associate themselves with this Blood so that It may speak on their behalf? How do the faithful participate in the Sacrifice of the New Law? All of these are accomplished by fruitfully participating, with faith, in the celebration of the Sacraments, particularly Holy Mass and the reception of Holy Communion. In this vein, as the Church presents in her Matins readings for this Feast, St. Augustine sermonized the following (120th Tract on John):

One of the soldiers with a spear pierced His Side, and forthwith came thereout Blood and Water. The Evangelist speaketh carefully. He saith not that he smote the Side, nor yet that he wounded It, nor yet anything else, but pierced It, to fling wide the entrance unto life, whence flow the Sacraments of the Church, those Sacraments without which there is no entrance unto the life which is life indeed… I have said that the Water and Blood shewed forth symbolically Baptism and the Sacraments.2

Blood crying out on behalf of the faithful, Blood as a source of divine life, Blood sealing a divine covenant, Blood as protection, Blood for the forgiveness of sins in sacrifice, and Blood as a means of purification. These are the considerations which the Church invites her children to ponder in their hearts on the Feast of the Precious Blood and, by extension, during this month of July. May you join her by so doing.

Fr. William Rock, FSSP was ordained in the fall of 2019 and is currently assigned to Regina Caeli Parish in Houston, TX.

- Translation taken from The Divinum Officium Project.

- See note 1.

July 1, 2023

Traditions of Ss. Peter and Paul

There are a vast number of ways for individuals and families to keep the feast of Ss. Peter and Paul, or “St. Peter’s Day”, as it has been colloquially known in English.

The first thing worth knowing for the modern Catholic is that, in most countries, it is still listed as a general Holy Day of Obligation, as we see in the current 1983 Code of Canon Law:

Can. 1246. §1. Sunday, on which by apostolic tradition the paschal mystery is celebrated, must be observed in the universal Church as the primordial holy day of obligation. The following days must also be observed: the Nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Epiphany, the Ascension, the Body and Blood of Christ, Holy Mary the Mother of God, her Immaculate Conception, her Assumption, Saint Joseph, Saint Peter and Saint Paul the Apostles, and All Saints. §2. With the prior approval of the Apostolic See, however, the conference of bishops can suppress some of the holy days of obligation or transfer them to a Sunday.

As indicated in the last sentence, however, bishops’ conferences can modify this list with approval, and that is indeed why this holy day is no longer of obligation in the United States and Canada. Nonetheless, Holy Mass has always been an important part of the day’s tradition, and many of the customs mentioned below take place at the parish church or after Mass on that day.

Below I have collected some traditions surrounding the feast of Ss. Peter and Paul, drawn from the immemorial liturgy of the Roman Rite itself as well as the folk customs of Rome and the wider world of Latin Catholicism. (Naturally, as the day is such an important one throughout all of Christendom, the various Eastern Rites have their own venerable traditions.)

Fasting on the Vigil

As you will see in your daily Missals, June 28th is the vigil of Ss. Peter and Paul. Like other vigils, it is a penitential day liturgically: the vestments are violet, and the Gloria is suppressed. It used to be a required day of fasting as well, but not for over a century in Canada and the Commonwealth nations, and not since 1842 within the United States.

Although fasting on the vigil is not binding on Catholics any longer, the faithful may keep it voluntarily if they wish. The only caveat is that one does not keep any fast on years where the vigil falls on a Sunday. Traditionally, churches would either simply skip fasting that year altogether, or fast on the Saturday before the vigil: June 27th.

Customs of the Feast Day

In antiquity the Pope on this day led a pilgrimage accompanied by the Roman faithful and anchored by two pontifical Masses– one at the Vatican, and then one at St. Paul’s Outside the Walls. But the long distance between them proved burdensome, so eventually St. Paul was given his own feast on June 30th.

La Girandola–“the Pinwheel”–is an elaborate fireworks show at Castel Saint’Angelo to the east of the Vatican, along the Tiber River. Tradition ascribes the show to the artist Michelangelo, although the celebration of saints’ days with fireworks seems to have been rather common in his day. Though suspended in 1886, it has been revived in recent years. Another old custom within the Vatican is to dress the statue of St. Peter in solemn papal vestments on the evening of the vigil, June 28th.

La Girandola–“the Pinwheel”–is an elaborate fireworks show at Castel Saint’Angelo to the east of the Vatican, along the Tiber River. Tradition ascribes the show to the artist Michelangelo, although the celebration of saints’ days with fireworks seems to have been rather common in his day. Though suspended in 1886, it has been revived in recent years. Another old custom within the Vatican is to dress the statue of St. Peter in solemn papal vestments on the evening of the vigil, June 28th.

Another Roman custom is the Infiorata–“flowering”—which was born on the 29th of June in 1625, when the head florist of the Vatican Benedetto Drei decorated St. Peter’s basilica with beautiful mosaic flower carpets. Though the custom was shortly after abandoned for almost four centuries, nearby places like the Alban Hills kept the tradition alive until it was finally restored to Rome in 2011. The artwork for the infiorata is elaborately planned and conceived, but for the feast families can easily do scaled-down versions at home. The general rule is to use the most natural materials possible–not only various colored flowers but also herbs, soil, coffee grounds, beans, etc. Begin by sketching out a drawing in chalk on the floor, then sprinkling coffee grounds or soil over the chalk to create the outlines of the drawing. Then fill each section with flowers or other materials as appropriate. Then, during a procession or at the close of festivities, the children are encouraged to walk or run across the images and erase them.

Nautical celebrations are very popular on this day. In many coastal communities around the world, from South America all the way to Gloucester, Massachusetts, June 29th is a day not only for carnivals, parades, and processions but also boat decoration and boat races. In Nice, on the French Riviera, the guild of fishermen has a custom to burn the boat of the poorest one among them, and replace it with a new one.

Landlocked regions may not be as able to keep maritime traditions, but they nevertheless have their own customs. In Hungary the feast day marks the beginning of the wheat harvest–with just a symbolic sweep of the scythe to respect the holiday from servile work. Hungarians bring grain, bread, and woven straw decorations to their churches to be blessed, and harvest wreaths were made and displayed until Christmas. In Alpine countries there was a tradition to kneel beneath a garden tree and recite the Angelus at the ringing of the Angelus bell, in order to receive the Papal blessing carried by angels throughout the world. Austria and Bavaria have a tradition of the Petersfeuer bonfire, perhaps an extension of the fires that traditionally accompanied the feast of St. John the Baptist on June 23rd.

The Foods of the Feast

Because St. Peter was originally a fisherman, seafood was prominent in the day’s cuisine.

There are a few species that were given the popular name of “St. Peter’s fish”. One is the John Dory (Zeus faber) of the Mediterranean Sea and the oceans of the Eastern Hemisphere; its unattractive appearance belies its excellent taste (see this recipe from Buon Appetito, Your Holiness: The Secrets of the Papal Table). It has a prominent round dark spot on its flank like a coin; so legend attached it to Christ’s miracle of the coin in the fish’s mouth, from Matthew 17:27.

Several other species in the Holy Land are called “St. Peter’s fish.” These are the Mango tilapia or Galilean St. Peter’s fish (Sarotherodon galilaeus), the common St. Peter’s fish (Tilapia zilli), and the Jordan St. Peter’s fish (Oreochromis aureus). The Galilean species was legendarily the fish multiplied in the Miracle of Loaves and Fishes; and these local Galilean recipes will enable you to treat the family to a taste of Peter’s home region.

Finally, when in 1868 the Trappists took over the Tre Fontane Abbey at the site of St. Paul’s martyrdom, they brought with them a recipe for chocolate that quickly earned them fame in the city. Since then, Romans have made it a habit of visiting them early on the morning of the feast and enjoying rosette rolls and hot chocolate amid the quiet peacefulness of the abbey’s eucalyptus trees. That’s right–having chocolate on the feast of Ss. Peter and Paul is a very Roman way to celebrate this very Roman feast!

Celebrating the Octave

The most important Catholic feast days were traditionally not over and done with in one day, but extended over a whole week of celebration. Ss. Peter and Paul enjoyed a common octave all the way up to 1955, when it was suppressed by Pius XII. The octave is therefore missing from missals printed after that day, although if you happen to have a pre-1955 Missal such as Lasance’s New Roman Missal, you will still find it listed.

Nothing prevents the faithful from still keeping the octave privately as a pious devotion. The simplest way to do that is to pray the collects of the Masses. On June 29th the prayer is as follows:

O God, who hast consecrated this day to the martyrdom of Thine apostles Peter and Paul, grant to Thy Church in all things to follow their teaching by whom it received the right ordering of religion in the beginning.

The next day, June 30th, is the feast of St. Paul, and both the pre-1955 and 1962 Missals have special collects:

O God, Who didst teach the multitude of the nations by the preaching of the blessed Apostle, Paul, grant us, we beseech Thee, that, venerating his natal day, we may experience the benefits of his intercession with Thee.

O God, Who, in conferring upon blessed Peter, Thine apostle, the keys of the heavenly kingdom, didst commit to him the priestly power of binding and loosing, grant that, by the help of his intercession, we may be delivered from the bonds of our sin.

On each day of the octave from July 1st to July 5th, the collect of the feast is said:

O God, who hast consecrated this day to the martyrdom of Thine apostles Peter and Paul, grant to Thy Church in all things to follow their teaching by whom it received the right ordering of religion in the beginning.

Finally, there is a unique collect for July 6th, the octave-day:

O God, whose right hand raised up blessed Peter, when he walked upon the waves, that he might not sink, and delivered his fellow-apostle Paul, thrice shipwrecked, from the depths of the sea, graciously hear us, and grant that, by the merits of them both, we may reach the glory of eternity.

Alternatively, the following commemoration can be made on each day of the octave from June 29th to July 6th:

Commemoration of Ss. Peter and Paul

Antiphon. Peter, the Apostle, and Paul, the Doctor of the nations, these have taught us Thy law, O Lord.

Verse. Thou shalt make them princes over all the earth.

Response. They shall remember Thy name, O Lord.

Let us pray.

O God, Who hast made holy this day by the martyrdom of Thine apostles, Peter and Paul, grant unto Thy Church that as through them she first received the faith, so may she in all things follow their precepts. Through Christ our Lord, Amen.

Celebrating Beyond the Octave

In a previous article I noted that, in Carolingian times, the long Post-Pentecost season was divided into various subseasons, and in this scheme, the feast of Ss. Peter and Paul was so important that it marked a transition from one subseason to another.

From the Pentecost octave to June 29th were the “Sundays of Pentecost” proper. After the feast was the Sunday post Natalem Apostolorum–“after the Birthday of the Apostles”. This last Sunday was followed by a sequence of six or seven numbered “Sundays after the Octave of the Apostles”, that filled up the time to the feast of St. Lawrence on August 10th.

This was a characteristically Roman arrangement. The Ambrosian rite of Milan did things quite differently, instead transitioning from the “Sundays after Pentecost” to the “Sundays after the Decollation” after the feast of St. John the Baptist on August 29th.

So, at least historically, the Roman liturgical books had a named liturgical subseason dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul that ran from the feast on June 29th to the vigil of St. Lawrence on August 9th. The name has since disappeared, so you won’t necessarily find it in your missals. But the evidence of it can still be seen in the Sunday Mass readings.

All of the Epistles of the 3rd to the 8th Sundays after Pentecost–which is roughly about the timeframe within which June 29th can fall–come from either the First Epistle of Peter or Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. And the readings for the 4th Sunday are Paul’s Epistle to the Romans prefiguring his martyrdom and the Gospel of Luke with St. Peter’s miraculous draught of fishes. This Petrine Gospel seems to be a clear case of the Sanctoral calendar making its mark on the Sunday calendar; as Fr. Francis X. Weiser points out, this also occurred with other highly venerated Roman martyrs like St. Lawrence and Ss. Cosmas and Damian.

As a way of restoring this “Petrine” subseason, families may wish to decorate their homes with extra images of the Apostles and their symbols (e.g. keys and swords). Having the children make and display scale model churches–particularly St. Peter’s in Rome–out of building toys fits the spirit of the season quite well. An important theme of the Post-Pentecost season is the growth and progress of the Church throughout the ages. So once we have already celebrated Peter and Paul’s martyrdom and founding of the Church over the octave, it is good to spend a little while meditating on how their Apostolic work helped build the institution of the Papacy, bring the Gospel to all the Gentile nations, and benefit the entire Church.

June 27, 2023

The New Founders of Rome, Part 1: the Feast

by Claudio Salvucci

According to legend, the city of Rome was founded on April 21st, 753 B.C. by a pair of twins named Romulus and Remus. When Remus made sport of Romulus’s still rudimentary defenses and leapt over them, he was killed for the slight, and so it was Romulus who gave his name to the city, became its first king, and established so many of its civic institutions, including its calendar and its religion.

According to legend, the city of Rome was founded on April 21st, 753 B.C. by a pair of twins named Romulus and Remus. When Remus made sport of Romulus’s still rudimentary defenses and leapt over them, he was killed for the slight, and so it was Romulus who gave his name to the city, became its first king, and established so many of its civic institutions, including its calendar and its religion.

As Ovid tells the story, Mars then prevailed upon Jupiter to deify Romulus:

“…he caught up Romulus, son of Ilia, as he was dealing royal justice to his people. The king’s mortal body dissolved in the clear atmosphere, like the lead bullet, that often melts in mid-air, hurled by the broad thong of a catapult. Now he has beauty of form, and he is Quirinus, clothed in ceremonial robes, such a form as is worthier of the sacred high seats of the gods.”

From then on, under the new name Quirinus, Romulus would be worshipped as a deity by the Romans. And April 21st, the putative day of the founding, continued to be celebrated throughout Roman history as the Natalis Urbis, the Birthday of the City. In A.D. 248, we hear that the reigning Emperor Philip the Arab celebrated the 1000th year anniversary of the city with “games of all kinds”.

But this was, perhaps, the last great celebration of the sort.

In the post-Constantinian era, as Christianity increasingly rivaled and then finally supplanted paganism, the character of Romulus came under increasing scrutiny. The Church Fathers repeatedly presented him as a man not worthy of emulation, much less deification, as we see in Augustine (City of God, 22:6), Tertullian, (De Spectaculis 5). Minucius Felix (Octavius, 25), and Lactantius (Divine Institutes, 20).

Augustine, as usual, is the most devastating in his rhetoric–not because he was the most polemical but because as a long-time admirer of Roman legends himself, he understood their flaws at a very deep level. With calm precision, and in his inimitable way, he contrasted the religion of Christ with the religion of Romulus:

For, not to mention the multitude of very striking miracles which proved that Christ is God, there were also divine prophecies heralding Him, prophecies most worthy of belief, which being already accomplished, we have not, like the fathers, to wait for their verification. Of Romulus, on the other hand, and of his building Rome and reigning in it, we read or hear the narrative of what did take place, not prediction which beforehand said that such things should be. And so far as his reception among the gods is concerned, history only records that this was believed, and does not state it as a fact; for no miraculous signs testified to the truth of this.

Christ was a more fitting deity than Romulus not only because He did the things that only a deity can do, but also because He was the fulfillment of a prophecy that long antedated Him. Augustine goes on to take apart the legend of Romulus piecemeal:

For as to that wolf which is said to have nursed the twin-brothers, and which is considered a great marvel, how does this prove him to have been divine? For even supposing that this nurse was a real wolf and not a mere courtesan, yet she nursed both brothers, and Remus is not reckoned a god.

Besides, what was there to hinder any one from asserting that Romulus or Hercules, or any such man, was a god? Or who would rather choose to die than profess belief in his divinity? And did a single nation worship Romulus among its gods, unless it were forced through fear of the Roman name?

He concludes his argument as follows:

And thus the dread of some slight indignation, which it was supposed, perhaps groundlessly, might exist in the minds of the Romans, constrained some states who were subject to Rome to worship Romulus as a god; whereas the dread, not of a slight mental shock, but of severe and various punishments, and of death itself, the most formidable of all, could not prevent an immense multitude of martyrs throughout the world from not merely worshipping but also confessing Christ as God.

In the late stages of an increasingly decadent Roman Empire, the Christian martyrs’ courage stood in stark opposition to the conduct of the age. Even though they served a different deity, the martyrs recalled by their courage a bygone Rome, appealing to those citizens who lamented the dissolution of the old Roman pietas that was in very short supply among their contemporaries.

Thus was the mind of pagan Rome opened to the revelation of Christ. And through her most famous martyrs of all, the Eternal City would inherit a new set of founding fathers to replace the ones they lost.

The New Founders

The Apostles Peter and Paul–a Galilean fisherman and a scholarly Pharisee–might be thought extremely unlikely candidates to replace Romulus and Remus. They were not even brothers in flesh, although they were brothers in Christ.

Yet they were very well situated for a Christian recalibration of the founding myth. As Pope St. Leo the Great said in his homily for their feast:

The whole world, dearly-beloved, does indeed take part in all holy anniversaries, and loyalty to the one Faith demands that whatever is recorded as done for all men’s salvation should be everywhere celebrated with common rejoicings. But, besides that reverence which today’s festival has gained from all the world, it is to be honoured with special and peculiar exultation in our city, that there may be a predominance of gladness on the day of their martyrdom in the place where the chief of the Apostles met their glorious end.

For these are the men, through whom the light of Christ’s gospel shone on you, O Rome, and through whom you, who was the teacher of error, was made the disciple of Truth. These are your holy Fathers and true shepherds, who gave you claims to be numbered among the heavenly kingdoms, and built you under much better and happier auspices than they, by whose zeal the first foundations of your walls were laid: and of whom the one that gave you your name defiled you with his brother’s blood.

These are they who promoted you to such glory, that being made a holy nation, a chosen people, a priestly and royal state, and the head of the world through the blessed Peter’s holy See you attained a wider sway by the worship of God than by earthly government. For although you were increased by many victories, and extended your rule on land and sea, yet what your toils in war subdued is less than what the peace of Christ has conquered.

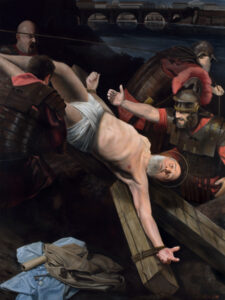

Even though Peter and Paul labored together in Rome, tradition has long maintained that they were martyred separately. The Prince of the Apostles died on the Vatican upon a cross. The Apostle to the Gentiles was beheaded along the Via Laurentina, as he was a citizen and could not be crucified.

One could certainly imagine a liturgical situation where St. Peter had his own feast and St. Paul had another completely separate one–but that is not what we see in the sources. Peter and Paul have been honored together on June 29th from time immemorial.

Dionysius, the Bishop of Corinth around the year 170, says that Peter and Paul “suffered martyrdom at the same time” (as quoted in Eusebius’s History of the Church II.25). But the passage does not offer any specific date. The actual feast day first appears in an ancient collection called the Chronography of 354, which contains a martyrology as well as a catalog of Popes. The first entry of the papal catalog is as follows:

Peter 25 years, 1 month, 9 days. He was in the times of Tiberius Caesar and Gaius and Tiberius Claudius and Nero, from the consulate of Minucius and Longinus [AD 30] to that of Nero and Verus [AD 55]. However he died with Paul on the 3rd day before the kalends of July, the emperor Nero being consul.

In the Depositionis Martyrum, a calendar of martyrs’ feasts in the same collection, the exact same date (the 3rd before the kalends of July) is given for Peter and Paul. Yet it also adds a puzzling note: “[during the] consulship of Tuscus and Bassus”. These two consuls are from A.D. 258, two centuries after Peter died. Some have surmised that the date must refer to a translation of the Apostles’ relics instead of their deaths, though there is also a Bassus who was consul under Nero in A.D. 64, complicating the matter.

As the papal catalog is meant as a historical document, its clear and explicit reference ought to command greater weight than an unclear reference mentioned as an aside in a liturgical calendar. Thus, considered together with the passage from Dionysius, it seems safest for history to side with the papal catalog that June 29th commemorates the actual deaths of Peter and Paul, and not merely a translation of their remains.

Finally, we cannot fail to mention another early tradition that is seen in St. Augustine (Sermo 295, 381), whereby Paul was indeed martyred on the same day as Peter, but not in the same year.

The Old Dates Prefiguring the New

So it was that Rome left off celebrating the date of founding by Romulus and Remus, and began celebrating Peter and Paul’s martyrdoms instead.

And perhaps Almighty God had already been preparing Romans for the transition through the natural course of history; sowing, long before Christ was even born, three seeds of the future Christian revelation into the ancient fabric of Italian paganism.

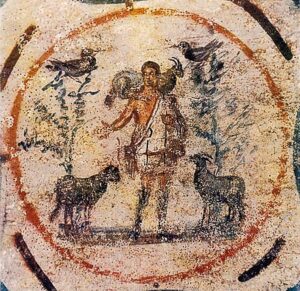

First, April 21st was not merely the secular date of Rome’s founding. It was also a religious festival called the Parilia, named for Pales, the god of shepherds and livestock, to whom the Romans prayed to keep the flocks fed and protected from diseases and wolves. Romulus and Remus’s association with shepherding was very strong; that was their occupation before they founded Rome, having inherited it from their foster-father, the shepherd Faustulus.

The season of the Parilia took on a deeper Christian meaning in the Roman Liturgy. Good Shepherd Sunday is the 2nd Sunday of Easter, which frequently falls around April 21st. The Epistle of St. Peter is read often in these early weeks of Eastertide, and at this Mass it anticipates the Gospel with the passage: “For you were as sheep going astray: but you are now converted to the shepherd and bishop of your souls.”

Thus, it would have been very natural for Roman Christians to see the Parilia as an anticipation not only of Christ the Good Shepherd but also Peter and his successors, who faithfully served their See with the words of the Risen Christ still resounding in their ears: “feed my lambs, feed my sheep.”

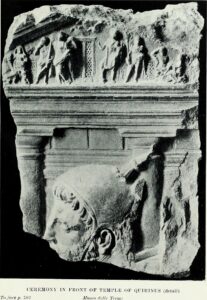

Second, on the Quirinal Hill there stood a temple dedicated to Quirinus/Romulus–said to be one of oldest temples in Rome, going to back to at least 293 B.C. and perhaps even earlier. At this temple was held the festival known as the Quirinalia, which took place annually on February 17th.

Note how close this date is to February 22nd, the second feast of the Chair of St. Peter. Despite its later associations with Antioch, this feast is Roman enough and ancient enough that it appears on the Chronography of 354. Christian Romans thus honored Peter in the very same week that their pagan counterparts honored Romulus, which no doubt strengthened the associations between the two.

Third is perhaps the most striking coincidence.

In 49 B.C., civil war was breaking out between Caesar and Pompey, and inauspicious portents like earthquakes and eclipses were alarming the Roman populace. The temple of Quirinus was consumed by fire. Lightning damaged a sceptre of Jupiter and a shield and helmet of Mars on the Capitol–the symbols of power of the very same gods who were said to have deified Romulus. To the Romans, it would have been crystal clear that divine wrath was falling on their city. And in hindsight, it looks rather like it was falling on their gods as well.

The temple of Quirinus was rebuilt and rededicated by Augustus in 16 B.C., and there remains to this day an ancient relief showing its restored pediment, with Romulus and Remus taking the auspices (image at right). This rededication occurred not during the traditional Quirinalia but in summer, after the Secular Games and just before Augustus left the city for Gaul. From Ovid we learn the exact date: the third day before the kalends of July.

Some sixteen years before the birth of Christ, roughly around the time that the Virgin Mary would likely have been born, the Romans began to celebrate a feast of their founders . . . on the 29th of June.

And they have been doing it ever since.

June 21, 2023